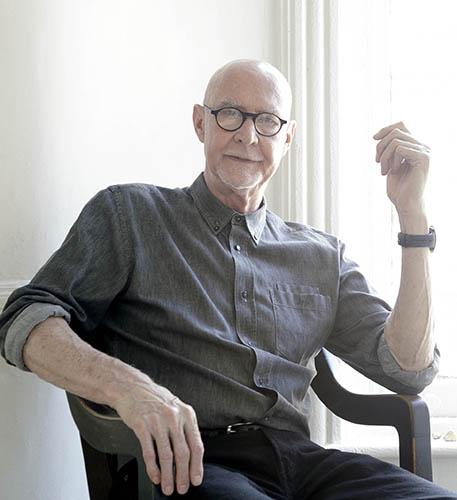

Art and cultural critic Douglas Crimp, the Fanny Knapp Allen of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies, will deliver the first lecture of the Humanities Center’s public lecture series for the 2017–18 academic year.

Crimp will give his talk—“Relying on Memory: From AIDS to Merce Cunningham”—on September 26 at 5 p.m. in Conference Room D at the Humanities Center in Rush Rhees Library.

“Memory and Forgetting” is the theme of this year’s lecture series, which will bring an array of speakers, including Nobel Prize–winning novelist Orhan Pamuk, contemporary artist Walid Ra’ad ’96 (PhD), neuroscientist Daniela Schiller, and Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, perhaps best known outside her field for penning the famous phrase “Well-behaved women seldom make history.”

Crimp will read from and reflect on several of his books, including his newest book, Before Pictures, (University of Chicago Press, 2016). In it, he turns inward to deliver a historical snapshot of New York City from the late 1960s through much of the ’70s, based on his own memories of New York’s art world and gay life in the period.

Ambivalent about calling the book a memoir, Crimp says its true subject isn’t his own story, but the era in which he lived: “Its genesis is my AIDS writing and activism,” he says. Accordingly, he terms the text a hybrid, a kind of history rooted in memory.

Crimp—whose other books include “Our Kind of Movie”: The Films of Andy Warhol (MIT Press, 2012) and Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (MIT Press, 2002)—uses memory-based writing in other works, too. A recent essay on choreographer Merce Cunningham, for instance, uses recollections about his own experiences with Cunningham’s art as its scaffolding. For that piece, memory is a “way to begin, to set up the more analytical aspects of the essay I want to write,” Crimp says.

But Before Pictures is different. There, recollections—both accurate and misremembered—serve a more fundamental purpose. The personal stake of a writer in a subject is essential, he argues, and academic prose often obscures it. He insists on his own “subjective position, my own partiality in both senses of the word. And I find that a useful corrective to the sort of performance of objectivity that’s in most academic writing,” he says.

Crimp is quick to note that he works as a critic, not a historian, and so is freed from the methodological requirements particular to that discipline. “But at the same time, [in Before Pictures] I think I’ve written a kind of history of New York City in a particular period that enriches our sense of what New York was, and not in spite of but because of the fact that it uses that partiality,” he says.