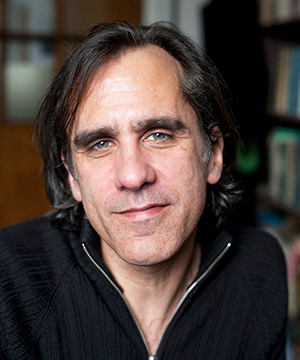

Earthling, the newest book of poetry by James Longenbach, the Joseph H. Gilmore Professor of English, had its roots in a poem he wrote called “Pastoral.”

“I heard something in it that sounded fresh to me,” he says, a different tone than in his previous poetry collection, The Iron Key (W. W. Norton, 2010). “It seemed to be talking about ordinary things, but in a way that made them seem at the same time kind of spectral or otherworldly. There was also the capacity for wry humor in that tone—and all of that seemed exciting to me.”

Written first, “Pastoral” ultimately became the final poem of Earthling, the poet and literary critic’s fifth poetry collection. The tone drove the book’s development, and the collection’s overarching narrative isn’t one of events, “but of feeling or spiritual development,” he says.

Publishers Weekly calls the book, which was published this fall by W. W. Norton, “a moving case for love’s power to sustain us.” Earthling moves constantly between the mundane and the mystical as it contemplates mortality, giving voice to a range of emotions that knowledge of life’s finiteness can create.

The book’s shifting viewpoints are exemplified perhaps nowhere more dramatically than in “The Crocodile,” a poem that playfully considers the perspective of that creature. But the whimsy also offers Longenbach an opportunity to reflect on his own mother’s death—an experience that, despite his efforts, had found no home in his poetry before.

“I don’t remember quite how it happened. I just got the idea of using this fanciful trope of the speaking crocodile as a way to get at the reality of this confrontation with mortality,” he says. The lines in the poem’s fourth section are plain and terse:

When my mother died,

I was right beside her.

She’d been unconscious for a day.

My sister and my father were there, too.

“It’s hard to get more flatly clear and straightforward in language than that,” he says, and hopes that what is evoked is also “spooky and revelatory.” He brings together the flatness of his language with the conceit of the crocodile as he ends the section:

Then, immediately, the color left her face,

She was no longer in her body,

And she sank beneath the lagoon.

“All I’m ever trying to do is to be scrupulously and absolutely clear about what I’m saying,” Longenbach says. “It’s become a discipline to me that has taken my poems to their strangest places, because trying to be very clear about things is a difficult, dangerous, and unsettling practice.”

Listen to James Longenbach read his poetry

Huntington Meadow

The Dishwasher

The title Earthling came to him when he discovered that it is one of the oldest words in the language, an Old English term for a person who plows or tills the earth.

“I’d assumed it was 1950s sci-fi speak: ‘Take me to your leader,’” Longenbach says. “I thought it was entrancing that ‘earthling’ was our name for a person intimate with the soil. And it seemed like the perfect emblem for the tone that was distinguishing these poems as they accumulated—the little earthling coming out of his hole in the ground to look about.

“It’s the vulnerability of it, yet the substantial inevitability and necessity of it, too.”

The Plutzik Reading Series will host James Longenbach for a reading from Earthling on November 30 at 5 p.m. in the Welles-Brown Room at Rush Rhees Library.