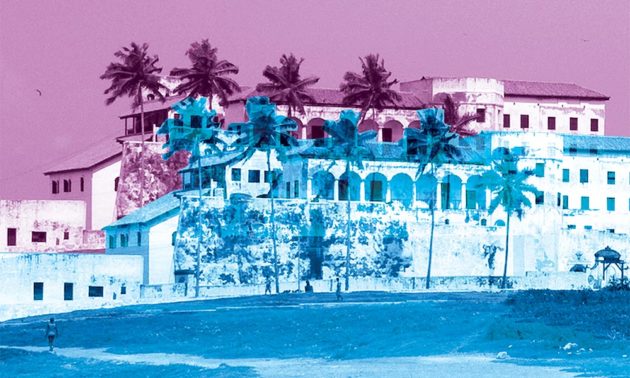

This is the second summer that University students – led by professors Renato Perucchio, Michael Jarvis, and Chris Muir – are studying the engineering, historical, and cultural aspects of the coastal forts of Ghana. They will be sharing their experiences from the field here on this blog.

By Ewan Shannon ’20

The last time I wrote an entry for this blog, I discussed how I intended to tackle all the unfamiliarities for my well- spent time in Ghana. Now that the field school has reached its end for the season, I look back with fondness and gratefulness for the opportunities I was presented. I suppose you could say I had many fingers in many pies. Dabbling in photogrammetry, structural analysis, NX modelling, total station data, and ethnographic work all in five weeks could certainly be considered a holistic experience. As an anthropology major, the latter of these experiences was something that I jumped on faster than you could spell “conspicuous consumption.”

Ethnographic study, the bread and butter of most anthropology, is something that, prior to my work in Ghana, I had very little personal experience with. Coming up on three years now, I have learned about the process, etiquette, and household names of ethnography in the classroom, and so I was very ecstatic about the opportunity to test my know-how out in the field and conduct a study for myself.

A week or two prior to the start of the field school’s ethnographic portion, the whole group wandered down to the shore outside of Elmina castle to take a closer look at the fishing boats in the process of being built. Although I’m still not entirely sure what happened, one man made it quite clear he didn’t like the looks of me (it turns out being 125 lbs. and as pale as a polar bear can intimidate people after all) and behaved towards me in a manner that made me uncomfortable. So, in my infinite wisdom, I decided that the shoreline was the safest and most ideal place for me to return to in order to conduct my ethnography. I never saw that fellow again, and in fact everyone else at the boat building area that I interacted with were very open and kind.

When you enter the town of Elmina, you’re always reminded that it’s a fishing town. The smell of the fish market is the first thing that gives it away, but it isn’t until you see the harbor absolutely crowded with boats of all colors, curiously flying the flags of any country under the sun, that you are in awe of the vibrancy the town is home to. Those boats immediately caught my attention and I knew I wanted my ethnographic study to focus on the boats and their builders. What’s with their flags and designs? Why are they built the way they are? What are they capable of?

An important step in any ethnography is to establish a good rapport with your correspondents. I was having little success until I made a breakthrough during my second day of interviews with the boat builders. As infinitely diverse as the cultures of the world are, it turns out that slapstick is universal. One of the boat owners was kind enough to let us climb aboard his vessel and talk to one of the builders, and of course I failed to notice a loose plank and would have plummeted straight down to the bottom of the boat if I hadn’t caught myself. Don’t let the word “boat” fool you—the hulls of these vessels are big enough that if I had fallen in, it would have called for a ladder to get me back out. I hoisted myself back up and looked over to see that the owner and his builders were all laughing at me. It was apparently enough to break the ice because they happily answered every question I threw at them and were equally as curious about me. I walked away that day with the nickname “Jonah,” after the biblical figure who was swallowed by a whale.

By the time I was back home in New York, I had an ethnographic paper I am very proud of to show for the rewarding work I did at Elmina. As I write this, my final grade for the field school hasn’t been posted yet, but I already know that my work this past month has paid off. In my last post, I discussed how a major benefit of my time in Ghana was how I was exposed to the unfamiliar, but another benefit has been how my knowledge of already familiar studies has been strengthened significantly through real-world application.

Ewan is a rising junior from Staten Island, New York. He is a Renaissance and Global Scholar majoring in ATHS (Archaeology, Technology and Historical Structures) and anthropology. He is particularly interested in conducting ethnographic work in the community surrounding Elmina castle and making photogrammetry models of the forts. Ewan is also an actor in the university’s International Theatre Program, and enjoys gardening, Civil War history, and Buster Keaton films.