In Class

A California Quest

Professor John Tarduno leads a group of freshmen and sophomores on a ‘field quest’ to explore the geology of the West Coast. By Ron Thomas ’71

|

| FIELD WORK: Students (Anna Wendt ’07, Megan Welsh ’07, Mary Ellen Chieco ’07, Jusin Gorski ’07, Benjamin Snyder ’07, and Kelly Hartman ’07 take notes. (Photo: Ron Thomas) |

The two vans of Rochester students stopped along Skyline Boulevard in the hills south of San Francisco, and everyone climbed out. Ducking under roadside bushes, they stepped into a clearing.

As at each stop, the freshmen and sophomores carried yellow field books in which they took notes and made sketches of the geological formations they had come 3,000 miles to see.

John Tarduno, professor and chair of earth and environmental sciences, pointed out two strips of land flanking a tree-filled valley. Shutter ridges, he told the students, are pieces of land that were moved out of place by the motion of a small fault.

“This is a clue that we’re getting close to the San Andreas Fault,” Tarduno said as the students dutifully took notes.

The opportunity to explore the fabled fault that runs north and south of San Francisco was one of the reasons the students had traveled across the country during spring break last March. It’s a highlight of Tarduno’s annual class, Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Mountain Ranges in California: A Field Quest.

For a week last spring, the class of geology neophytes traveled to the Bay Area to intensely study the fault and other land formations that can’t be found in the Rochester area.

The course is part of Rochester’s Quest program, a set of small classes designed to introduce freshmen and sophomores to a field of study by exploring research and scholarship firsthand. Many use nontraditional learning environments, an approach that’s ideal for a discipline like geology.

This year, only four of Tarduno’s 10 students had taken Geology 101 before heading west along with him, teaching assistants Gail Lee Arnold and Risa Madoff, and two of Tarduno’s former students, Mike Meyers and Mike Nugent, who drove two vans for everyone.

“At the end of the course, we end up with 50 percent geology majors,” Arnold said.

That’s partly because the annual trip to California is a rare rocky relationship that people enjoy.

During the week, the class spent three days in the Bay Area, the site of the famous 1906 earthquake and fire that destroyed much of San Francisco and the Loma Prieta earthquake that temporarily halted the 1989 World Series.

Next came 1 1/2 days trekking through gorgeous Yosemite Park and three days under the scorching sun of Death Valley, the lowest point in North America at 282 feet below sea level.

By the time they flew from Las Vegas back to Rochester, each van had traveled 2,500 miles—more than three times the length of California.

For some students, it’s an introduction to a new world.

|

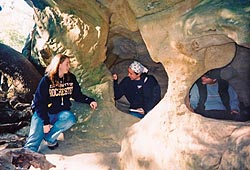

| Students explore geological formations in Castle Rock State Park. (Photo: Ron Thomas) |

“I don’t really know what my major is,” said Katrina Rudd, a freshman from Maine. “I just wanted to have an experience where I would get to see what geological science is all about without learning from a textbook.”

For others, such as freshman Kelly Hartman from Long Island, the California adventure confirmed that geology fits her interests.

“This is what I’ve done on vacation all my life,” she said. “My mom’s best friend is a geologist and this is what we did on vacation. I enjoy camping and being outdoors because you can get away from TV and video games. That can stress you out. This is very relaxing—being outdoors.”

That’s especially true considering some of the other places Tarduno has taken his students. A Rochester professor for 11 years, he has led five expeditions to the Arctic during which he takes along about a half dozen older undergraduates. The California trip isn’t nearly as physically challenging, yet Tarduno makes it academically rigorous by giving his students impromptu quizzes every stop along the way as they learn to think and see like geologists.

At Castle Rock State Park—3,600 acres of forest amid a sprinkling of steep canyons about 60 miles south of San Francisco—Tarduno led the students to a whimsical rock formation pocked with cavities big enough to climb into.

Standing on the rocks above them, Tarduno began the day’s questioning.

“What kind of rock?” he asked. “What size of fragments do you see?”

When answers weren’t forthcoming, he explained that they were looking at a classic outcrop of sandstone, 20 to 50 million years old.

At the Monte Bello Open Space Preserve, Tarduno pointed out Black Mountain, “where the motion of the 1906 earthquake stopped.” He also pointed out the fault line that caused the Loma Prieto earthquake.

At Los Trancos Open Space Preserve, the students saw a testament to the power of earthquakes. After walking down a slight incline, they stood in the shade facing two wooden fences—a reconstruction of a fence that the 1906 earthquake broke into two pieces—separated by about six feet of ground. The gap was wide enough for students to pose between the “two” fences for an unofficial class picture.

On the drive north on Highway 280, deservedly called the most beautiful highway in America, the class stopped at a rest stop for a picnic lunch of juice, carrot sticks, and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. (Freshman Benjamin Snyder dared to be different, so he had peanut butter and jelly on a tortilla.)

Then it was time to get back to the vans and off to the Crystal Springs Reservoir, which Tarduno declared was “the site of a really bad James Bond movie.”

Time, in other words, to get back to business.

“Can someone point out a shutter ridge?” Tarduno asked.

Ron Thomas ’71 is a freelance sports writer in the San Francisco Bay Area.