Exploring Hip Hop’s Hold on Women

As a self-described member of the “hip hop generation,” T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting ’89 says the music in the 1980s included voices that resonated with her.

“The hip hop I grew up with explored gender and race in interesting ways,” she says, citing performers like Queen Latifah who offered a female perspective on sexual politics, urban youth, and other subjects.

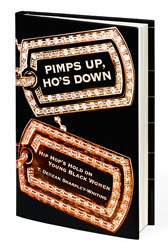

But as hip hop has grown more successful commercially, it has also grown more sexist and more violent, she says. In her new book, Pimps Up, Ho’s Down: Hip Hop’s Hold on Young Black Women (NYU Press, 2007), Sharpley-Whiting investigates the interactions between hip hop, gender politics, and American popular culture.

The title is a response to hip hop’s depiction of women as disposable commodities, held in their place by charismatic men. She calls the book an attempt at “intervention” in hip hop culture.

Pimps Up, Ho’s Down “dwells in the space between hip hop and feminism,” she says.

Drawing on Sharpley-Whiting’s interviews with filmmakers, videographers, exotic dancers, hip hop groupies, college women and recent graduates, the book considers such questions as how color prejudice permeates hip hop culture, how ideas of mainstream beauty culture portrayed in hip hop videos affect young black women, and how lyrics and videos encourage sexual abuse of young black women.

“The issues speak broadly to women,” she says, noting that the book is intended for a general audience, not just an academic one.

For Sharpley-Whiting questions about hip hop lead to questions about the larger culture that has produced it.

“I think it’s very easy to scapegoat hip hop,” she says. “It’s not that there aren’t problems with it—that’s why I wrote the book. But it’s easy to scapegoat hip hop because it’s so raw.” An analogy, she says, is early rock ’n’ roll, when people “projected cultural angst” onto a new form of music.

“We’re not being honest about the culture of incivility toward women, and black women in particular, that is part of our culture,” Sharpley-Whiting says. “If hip hop were to go the way of the dinosaur, would we still have misogyny?” she asks rhetorically.

Television commentators and others have found hip hop easy to blame for the violence, sexism, and incivility endemic in American society, Sharpley-Whiting says. The music is just one manifestation of those impulses, she argues, and the kind of confrontational talk shows that so often target hip hop are another.

Speaking of the larger American culture, she says, “We have to recognize that we find demeaning women, demeaning people, incivility in general, very entertaining. We love it, we listen to it, we want to hear them hollering.”

While she is dismayed by many of the trends in hip hop and their effects on young black women, Sharpley-Whiting finds value in the music as a whole.

“The aesthetics are being overshadowed by permutations in commercial hip hop. There are alternative hip hops,” she says. “We are passive consumers. We turn on the radio, we hear the music, and we think that’s all the hip hop out there. But if we’re going to talk about hip hop, we need to be more knowledgeable about it.

“Commercial hip hop impoverishes the art form,” she adds, “and we lose track of the fact that it is an art form.”

When Sharpley-Whiting came to Rochester as an undergraduate, students from New York City exposed her to forms of rap music more varied than she had known growing up in St. Louis.

“I embraced things that weren’t me,” she says. “I was still deeply wedded to my Southern roots. For me it was a moment of cultural mixing.”

A French major, Sharpley-Whiting also enrolled in many history courses that helped to send her on her professional path. After graduating from Rochester, she earned her Ph.D. at Brown University.

“There was a whole cadre of historians—Eugene Genovese, Elias Mandala, Joseph Inikori, and Jesse Moore—who opened up a new door for me, and a global perspective.”

A professor of French and African American studies and director of African American studies at Vanderbilt University, Sharpley-Whiting writes for popular audiences in publications such as Ebony magazine. She is also returning to scholarship on French history with a book now under way on African American expatriates in Paris during the 1920s and ’30s.

While she appreciates the secure ground a scholar can stand on when studying figures well in the past, she regards her new book with particular favor.

“This book has touched me in a way no other book I’ve written has,” she says.

—Kathleen McGarvey