Features

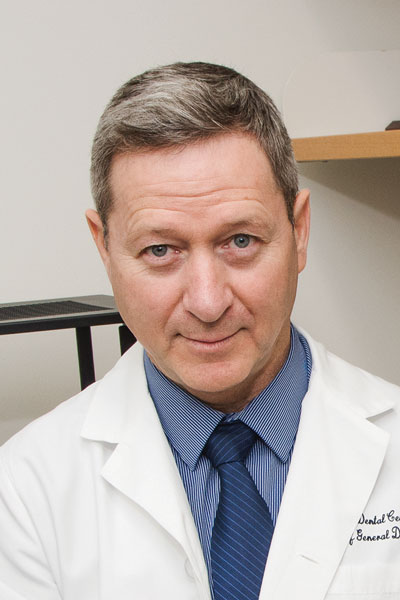

ADVANCING PUBLIC HEALTH: When the Rochester Dental Dispensary opened in 1917 to provide care to area children (below), there was only one other clinic in the nation—Boston’s Forsyth Dental Infirmary—that rivaled its mission and scope. Hans Malmstrom (above), chair of the Advanced Education in General Dentistry program, is a leader in training oral health practitioners for clinical and academic roles. (Photo: Eastman Institute for Oral Health)

ADVANCING PUBLIC HEALTH: When the Rochester Dental Dispensary opened in 1917 to provide care to area children (below), there was only one other clinic in the nation—Boston’s Forsyth Dental Infirmary—that rivaled its mission and scope. Hans Malmstrom (above), chair of the Advanced Education in General Dentistry program, is a leader in training oral health practitioners for clinical and academic roles. (Photo: Eastman Institute for Oral Health)When Eli Eliav was a dental student in Jerusalem, one of his classmates achieved a rare distinction: he was accepted to the postgraduate dentistry program at the Eastman Dental Center in Rochester. Located adjacent to the Medical Center, the dental facility was not yet fully integrated with the University, but the clinical training program run collaboratively by the two institutions was world renowned.

“Accepted to Eastman! I envied him so much,” Eliav says. “If anyone told me that I’d be the director of this institution 20 or 25 years later, I would say that’s crazy. But this is a fact.”

Eliav has been the director of the Eastman Institute for Oral Health since 2013. The institute adopted its name in 2009 as a reflection of the full integration of research, education, and clinical care in oral health into a single entity within the Medical Center.

(Photo: Eastman Institute for Oral Health)

(Photo: Eastman Institute for Oral Health)The institute, which traces its origins to the opening of the Rochester Dental Dispensary in 1917, turns 100 this year. It’s routinely among the top 10 recipients of grant funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Each year, more than a thousand applicants from around the globe compete for roughly 50 spaces in one of the institute’s eight postdoctoral training programs.

Last fall, the American Dental Education Association conferred on the institute its highest honor: the William J. Gies Award for Achievement in Academic Dentistry and Oral Health.

Leading the planning of this year’s centennial celebration is Cyril Meyerowitz ’75D, ’80D (MS). Eliav’s predecessor, Meyerowitz successfully implemented the merger of the Eastman Dental Center with the University in 1997. The highlight of the celebration takes place in June, when clinicians and researchers from around the world, including many distinguished alumni, arrive in Rochester to take part in a two-day symposium on the future of oral health, culminating in a gala celebration.

AN EASTMAN TRADITION: Eliav, director of the institute since 2013 and an expert on neuropathic pain, combines accomplishments

in research with a commitment to the kind of clinical service the Rochester Dental Dispensary was founded a century ago to

deliver. (Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health)

AN EASTMAN TRADITION: Eliav, director of the institute since 2013 and an expert on neuropathic pain, combines accomplishments

in research with a commitment to the kind of clinical service the Rochester Dental Dispensary was founded a century ago to

deliver. (Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health)The Rochester Dental Dispensary was built with funds provided primarily by George Eastman. Eastman’s interest in dental care came from his recognition that dental health was an integral part of overall health. What started as a facility to provide basic care and training grew, in an eventual merger with the University, to become an internationally distinguished center for dentistry built on the three pillars of research, specialized training, and clinical care.

It’s an unusual model in at least two respects. First, there is no program leading to the doctor of dental science (DDS) or doctor of medicine in dentistry (DMD) degrees. Instead, the institute’s educational mission is to provide postgraduate training.

Second, its clinical care is targeted to underserved populations. They’re a diverse group themselves, including people in poverty, geriatric patients, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and others with complex, ongoing medical conditions.

It’s a model that allows the institute to concentrate its resources in areas of strength—strength that helps it maintain itself as the enviable institution that Eliav could scarcely envision himself leading so many years ago as a student in Jerusalem.

Beginnings

When George Eastman was a boy in the 1860s, a budding dental profession served mostly the well-to-do. To a large degree, dental work was considered luxury care. For most people, problems with teeth, usually encountered by early adulthood, were taken care of by a tooth puller—often an itinerant laborer who provided painful extractions with rudimentary tools.

Change came quickly in the early 1900s. Many physicians and civic leaders began to recognize the broad social consequences of poor public health. Eastman—who had lost all of his teeth by early adulthood—developed an interest in dental care, based on the forward-thinking idea that oral health was integral to general health.

The City of Rochester was an early leader in dental care. As Elizabeth Brayer tells the story in Leading the Way: Eastman and Oral Health (University of Rochester Press), the Rochester Dental Society established what’s believed to be the nation’s first free dental clinic in 1901.

In early 1915, a committee of citizens and dentists met to plan for additional clinics. But Eastman had another idea. He proposed one central clinic instead. He’d been following the development of a large dental infirmary in Boston—what would become the Harvard-affiliated Forsyth Institute. As he wrote to the committee chairman, William Bausch, “I should not care to have anything to do with this affair unless a scheme be devised which will cover the whole field and do the work thoroughly and completely and in the best manner.”

(Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health)

(Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health) MEETING PATIENTS WHERE THEY ARE: Institute dentists deliver general and specialized care to underserved and difficult-to-reach

populations. Mobile units serve geriatric patients (top); and institute dentists screen children with intellectual and developmental

disabilities at a Special Olympics event (above). (Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health)

MEETING PATIENTS WHERE THEY ARE: Institute dentists deliver general and specialized care to underserved and difficult-to-reach

populations. Mobile units serve geriatric patients (top); and institute dentists screen children with intellectual and developmental

disabilities at a Special Olympics event (above). (Photo: Keith Bullis/Eastman Institute for Oral Health)No doubt inspired by Forsyth’s example, Eastman reasoned that a central clinic would be able to train much needed dental hygienists more efficiently. Hygienists would then travel to schools to provide basic cleaning and checking, and refer difficult cases to the central clinic.

With his conditions met, Eastman agreed to finance what became the Rochester Dental Dispensary. It opened in October 1917 in an expansive building at 800 East Main Street, sporting nearly 70 operating units, a research wing, a library, special examination rooms, and a children’s waiting room adorned with whimsical murals and a large birdcage.

A Fortuitous Opportunity

The dispensary flourished in its first years. Preventive care began at birth, as the director, Harvey Burkhart, sent notices to Rochester parents of newborns instructing them to bring their babies to the dispensary at the first sign of teeth. Meanwhile, twice a year, a corps of hygienists fanned out to Rochester schools to provide basic preventive care to children up to 16 years of age.

Eastman might have been satisfied had his contribution to the oral health of the local community ended with the establishment of the dispensary. But in 1920, he was presented with an unexpected opportunity.

As part of a national movement to improve physician training, the John D. Rockefeller Foundation was offering millions of dollars to help establish modern schools of medicine. The University of Rochester seemed a promising destination to the educator leading that movement, Abraham Flexner, who thought that given Eastman’s support for dentistry, he could easily persuade this progressive philanthropist to support a medical school.

Following a meeting with Flexner and then University President Rush Rhees, Eastman offered his support—provided the school be designed to offer both medical and dental education.

What Kind of Dental Education?

“I did not foresee that [the dispensary] might have an opportunity to become a part of a greater project for a higher grade of dental education than had before been attempted,” Eastman wrote to the dispensary trustees in June 1920.

He envisioned a close partnership with the school, whose trained dentists would enable the dispensary to expand the services it offered. But when the school opened in 1925, it was unable to attract candidates in dentistry. Among the reasons was that the school required dental and medical students to take the same coursework in their first two years. Other dental schools required far less of their entering students.

What emerged instead was the University of Rochester Dental Research Fellowship Program. It was consistent with the vision of the school’s first dean, George Whipple, a pathologist and dean at the University of California Medical School who came to Rochester as an unabashed proponent of building a research-oriented institution.

Joining Forces

When the Eastman Dental Center merged with the Medical Center in 1997, then President Thomas Jackson declared, “The question is not why the merger happened, but why it took 70 years.”

The reasons are various, including concern on each side about sacrificing independent control over resources and priorities. But as early as the mid-1960s, both institutions discovered they were less independent of the other than they imagined. The strengths on which they prided themselves could only be maintained in partnership.

In its early years, the dispensary focused on clinical care and training, leaving research to the University. But in the 1950s and 1960s, under the direction of Basil Bibby ’35M (PhD), the dispensary put significant resources into research. It added a new research wing, hired aggressively, and in 1965 changed its name to the Eastman Dental Center, in recognition of a mission that had expanded beyond basic treatment and training.

While the center’s resources were impressive, the University lagged in attracting students and found itself heavily dependent on the center’s resources to win coveted grants from the National Institute of Dental and Cranial Research.

But the center faced challenges, too. Because it was not affiliated with a hospital, its educational programs didn’t meet the standards for approval by the American Dental Association.

As the 1960s drew to a close, both institutions were at a turning point. The next decade would bring a formal affiliation, as well as the Eastman Dental Center’s move from its East Main Street home to a new facility adjacent to the Medical Center. “Dentistry is a specialty in the medical field,” declared the president of the Eastman Dental Center’s board in justifying the move.

Although a merger was still years away, the center’s relocation facilitated the collaborations that would lead eventually to it.

The Institute at 100

The merger of the city’s premier dental institution with the region’s major medical center may look inevitable in hindsight. That’s because it reflects the direction in which dentistry had been moving for quite some time.

“What we’ve been doing at the institute is way beyond the basics,” Eliav says. “We’re improving the quality of lives on many levels.”

As advanced dentistry begins its second century in Rochester, it’s clear that dentistry is now more fully integrated into general medicine than ever before, and more integral to medical treatment and research than many laypersons realize. That integration is apparent in the institute’s research, education, and clinical care.

Research

Research takes place throughout the institute, including the Center for Oral Biology—a direct descendent of the Dental Research Fellowship Program that the Medical Center established in 1929.

Housed in the Arthur Kornberg Medical Research Building, the center underscores the way in which dentistry and other areas of medicine are interrelated.

For example, Wei Hsu, who holds the title of Dean’s Professor at the Center for Oral Biology, discovered early in his career that a gene implicated in cancer also played a prominent role in craniofacial development and disease. Recruited to the institute in 2002, he’s conducting pathbreaking research on stem cells and skull deformities.

Catherine Ovitt, an associate professor at the center, has achieved national recognition for her research on the repair and regeneration of the salivary glands—critical for oral health, yet often seriously damaged during treatment of head and neck cancers.

Along with principal investigator Dorota Kopycka-Kedzierawski, an associate professor of dentistry, several more institute researchers are exploring the effects of stress and parenting behaviors on early childhood caries—a significant public health problem that disproportionately affects children in poverty.

The National Institutes of Health has recognized the institute not only by the grants it has awarded, but also by selecting it in 2012 for a leadership role in a $67 million national research initiative to improve clinical care.

Education

“In New York, there are five dental schools and us,” says Eliav. “We train the teachers and leaders of dentistry.”

Among those leaders is Martha Somerman ’78D, ’80M (PhD), who completed institute training in periodontics and a doctorate in pharmacology at the Medical Center, and is the director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Institute graduates serve in leadership roles in universities around the world. Most recently, after being approached by a team from Kuwait University, the institute partnered with that university as well as Damman University in Saudi Arabia to train dentists from the two Middle Eastern nations for clinical and research faculty positions in their expanding dental schools.

Eliav—who holds a dental degree as well as a doctorate in neuroscience, and researches neuropathic pain—emphasizes the need for oral health faculty who have degrees in both clinical dentistry and research.

“One of the problems we’ve had in health care,” he says, “is the lack of connection between the clinical work and research. We need more clinicians who are involved in research and more researchers who understand patients’ needs.” Given the scarcity of candidates with substantial research and clinical backgrounds, the institute often recruits faculty from among its top graduates.

The institute also leads in training practitioners to treat specific populations, including patients with complex diseases who have unique needs, older adults, and patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Eliav says there’s a paucity in the medical literature about treating such patients, and institute faculty are developing protocols that will help dentists treat them.

Clinical Care

There are about 180,000 patient visits each year to institute facilities. They include visits from thousands of patients who have no other option for care. Many of these patients are on Medicaid, which institute-affiliated dentists accept, and most private practitioners do not.

Among them are children in poverty who receive care at all Eastman’s locations as well as at a mobile dental unit called the Smilemobile. The first Smilemobile (there are now several in active use) was developed for the Eastman Dental Center in 1967 by the Sybron Corp. and Wegmans Food Markets. It was designed to provide care to targeted underserved populations, which at that time meant primarily central cities and rural areas. Today, the mobile units serve about 8,000 patient visits per year by traveling to schools and day care centers throughout the region, “If it weren’t for the Smilemobile, a lot of our kids would get no dental care at all,” says Darlene Pelow-Sullivan, a social worker at School No. 2 in Rochester. “They would be suffering from abscesses and decay. You can’t learn if your mouth is hurting.”

This year marked the introduction of an additional Smilemobile. Funded through the United Way by the family of Joseph Lobozzo, founder of the Rochester optical design and manufacturing firm JML Optical, it’s the first unit in the fleet to be outfitted especially for patients with physical, developmental, or intellectual disabilities, as well as other medically complex conditions.

But while institute dentists travel to serve patients, many patients travel distances to receive care from them. The institute is a regional destination for specialized oral health care. Patients with a range of birth defects—cleft lip and palate, severe underbites that interfere with speaking as well as eating, to name just two examples—come to the institute to be treated by highly trained specialists.

The University’s new Complex Care Center, opened last spring, is a cutting-edge facility for coordinated treatment of patients with a host of conditions that make dental care a challenge. It’s there that institute students are being trained to treat patients with special needs.

Among the admirers of the institute is Christopher Fox, the executive director of the International Association for Dental Research. Fox, who will be leading a plenary session, along with Eliav and Meyerowitz, at the June symposium, says the institute’s clinical programs are “innovative, and a model for the provision of dental services to the underserved.”

Its research and training, meanwhile, serve as a prototype for “how research will lead to the improvement of oral health worldwide.”

“This is a critical time for the dental profession,” he adds. “We have to make decisions today that will determine the future of the profession, most importantly how we will interact with the larger health care world. [The Eastman Institute for Oral Health] will continue to play a leading role in that planning.”

For more on the centennial celebration of the Eastman Institute for Oral Health, as well as the institute’s history, visit the website “Celebrating 100 Years” at www.urmc.rochester.edu/dentistry/centennial.aspx.