She didn’t want to live.

Her bed was one of the things that Lauren Opladen missed the most. So when she finally got back after a month away from home, that’s where she headed.

Her bed was one of the things that Lauren Opladen missed the most. So when she finally got back after a month away from home, that’s where she headed.

The sheets were cool and soft. The blankets, heavy and comforting. She felt safe. And as she fell asleep, she thought happily that she might never want to get out of bed again.

But by morning, something profound had changed. She still didn’t want to leave her bed, but the warm, content feelings were gone, replaced by those far more ominous. And as the morning wore on, they became more and more acute.

No, she didn’t want to get out of bed. She didn’t want to move. She didn’t want to do anything. She didn’t want to live.

People who have been close to a suicide — those who have had either a family member or close friend take their own life — are at much higher risk at attempting it themselves. “It can definitely be a red flag for us as counselors,” said Matt Drury, therapist in the partial hospitalization program at Golisano Children’s Hospital.

When Lauren attempted to take her own life, six years had passed since her older brother, Joshua, had taken his at age 17.

Four years later, Lauren’s father — for whom she had been a primary caretaker — passed away from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Her family then moved from Greece to Spencerport, upending her social life. And after a surgery for congenital hip dysplasia, which required a year of rehabilitation, Lauren was unable to play soccer, which had been her primary escape for years.

“A lot of things were just going downhill,” she said.

But at this crucial period in her life, with many of her safety nets falling apart, she did the one thing that comes as difficult to many teens in a similar position: She sought help.

“I had a close friend who was also struggling, and we both told each other the same thing: If it gets bad, make sure to speak up,” said Lauren. “A water bottle can only fill up so much before it overflows.”

Getting help

Lauren’s first attempt to get help came in the form of Golisano Children’s Hospital’s partial hospitalization service, a program where teenagers struggling with suicidality and other significant mental health concerns stay in the hospital from Monday through Friday during school hours. The program accommodates 22 teens at any given time — that number will increase to 33 once the new Golisano Pediatric Behavioral Health building opens later this year — and priority is given to those who are struggling with severe depression but can safely stay at home during evenings and weekends.

The program is a mix of various therapies, including one-on-one sessions, group discussions, and activity therapy, such as music or art therapy. There’s also some classroom learning mixed in — care providers coordinate with the student’s teachers to ensure they don’t fall too far behind on schoolwork.

One major goal of the program is to establish a solid safety plan for when suicidal thoughts set in, which means identifying supports and developing coping mechanisms.

“We go through warning signs, triggers for major stressors, and talk about who is their major support system,” said Drury, who served as Lauren’s primary therapist when she was in the program.

Once equipped with these coping tools, some patients get their feet underneath them and are able to return to care in an outpatient setting. Others need more support.

Lauren initially spent time in partial hospitalization, but her depression continued to grow worse, so she was admitted into the inpatient unit, where patients spend 24 hours a day. She remained there for a month before she was moved back to the partial hospitalization.

She got home that first night, missing her bed. That next day was when she woke up, wanting to end her life. She attempted suicide that morning.

After the attempt, she spent another month back in the inpatient unit. She engaged in more work, more discovery, and more treatment. It’s hard for her to put her finger on what, specifically, helped her symptoms improve. But that month, she says, was a turning point.

After the attempt, she spent another month back in the inpatient unit. She engaged in more work, more discovery, and more treatment. It’s hard for her to put her finger on what, specifically, helped her symptoms improve. But that month, she says, was a turning point.

“The staff just really helped me,” she said. “They were a big part of my recovery because I really gained a connection with many of the people there. I knew I could talk to them — even now, I’ll go and visit them sometimes.”

Upon release, she transitioned to an outpatient care setting, and began seeing a therapist once a week.

Hope for the future

“It is important to meet a patient where they are at, identify what progress they’d like to achieve in treatment, and engage in safety planning to help prepare for more challenging days. Lauren engaged well and worked to identify activities to engage in that she enjoyed to help mediate challenging events or stressors,” said McKenzie Smallcomb, Lauren’s clinician at the children’s hospital’s Behavioral Health and Wellness Outpatient Services. “Lauren exhibited many strengths that contribute to resiliency including empathy for others and humor. She was always talking about being there for others.”

With Smallcomb, Lauren was able to expand on the safety plan that she’d developed with Drury. Now, Lauren has celebrated many exciting life updates, welcoming a pit-bull mix named Chief—who she adores and walks every day—and her graduation from The College at Brockport with a nursing degree. She is now an Intensive Care Unit nurse at Strong Memorial Hospital and continues her advocacy for mental health services.

With Smallcomb, Lauren was able to expand on the safety plan that she’d developed with Drury. Now, Lauren has celebrated many exciting life updates, welcoming a pit-bull mix named Chief—who she adores and walks every day—and her graduation from The College at Brockport with a nursing degree. She is now an Intensive Care Unit nurse at Strong Memorial Hospital and continues her advocacy for mental health services.

The coping skills she learned have been suiting her well as of late. But Lauren knows that her symptoms could come back. And that’s why, she’s sharing her story: She wants anyone who reads it to do the same thing if they are struggling.

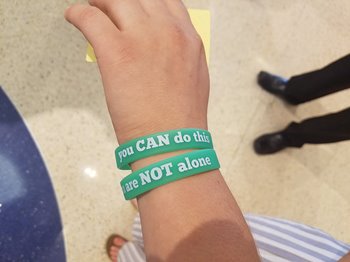

“You have to tell someone,” said Lauren. “No one can do it alone.” Fortunately, she’s not afraid to ask for help.

—Story by URMC Communications, March 4, 2019. Updated January 2024