The community-engaged learning program at the Center for Community Engagement challenges students and faculty to reconsider where learning happens. Presentations by students in Writing, Speaking, and Argument courses Being Homo Sapiens Sapiens: The Brain, The Mind, The Heart, and Full Catastrophe Living and Translation: Interpreting and Adapting, emphasize that our natural world has a lot to teach us when it comes to engaging with community.

Since 2021, Professor Stella Wang has partnered with the Ganondagan State Historic Site and the Digital Scholarship department at River Campus Libraries to explore the human and ecological histories of Rochester, especially its Haudenosaunee roots. Out of this partnership emerged the YoUR Nature Walk, which Stella describes as “an interactive map that provides information about the natural world around campus, […] encouraging self-guided nature walks for a range of health, environmental, and relationship benefits while foregrounding the university-Native-community collaboration.” The map is continuously updated each semester based on Story Maps created by students in Being Homo Sapiens Sapiens, and topic-specific research pieces by students in the translation course – all guided by the continued collaboration with Ganondagan.

Charley Pecora ‘29 shared that she takes frequent nature walks herself, but going on a campus nature walk led by Trish Corcoran, Onondowaga/Seneca naturalist and writer, helped her connect with the natural environment of Rochester, which will be her home for the next four years. Charley’s reflection nods to the importance of fostering relationships not only with local residents, but with nature.

On October 30, students presented one of their course projects – an individual Story Maps digital writing project with a companion, hands-on, multimodal project involving a small canvas sling bag. They set up their presentations at tables in Lam Square, allowing for intimate conversations about their research. Stella, Trish, and Blair Tinker (GIS-specialist, who ran a map-making workshop for students’ Story Maps) were also on site to chat and add further context to the students’ work.

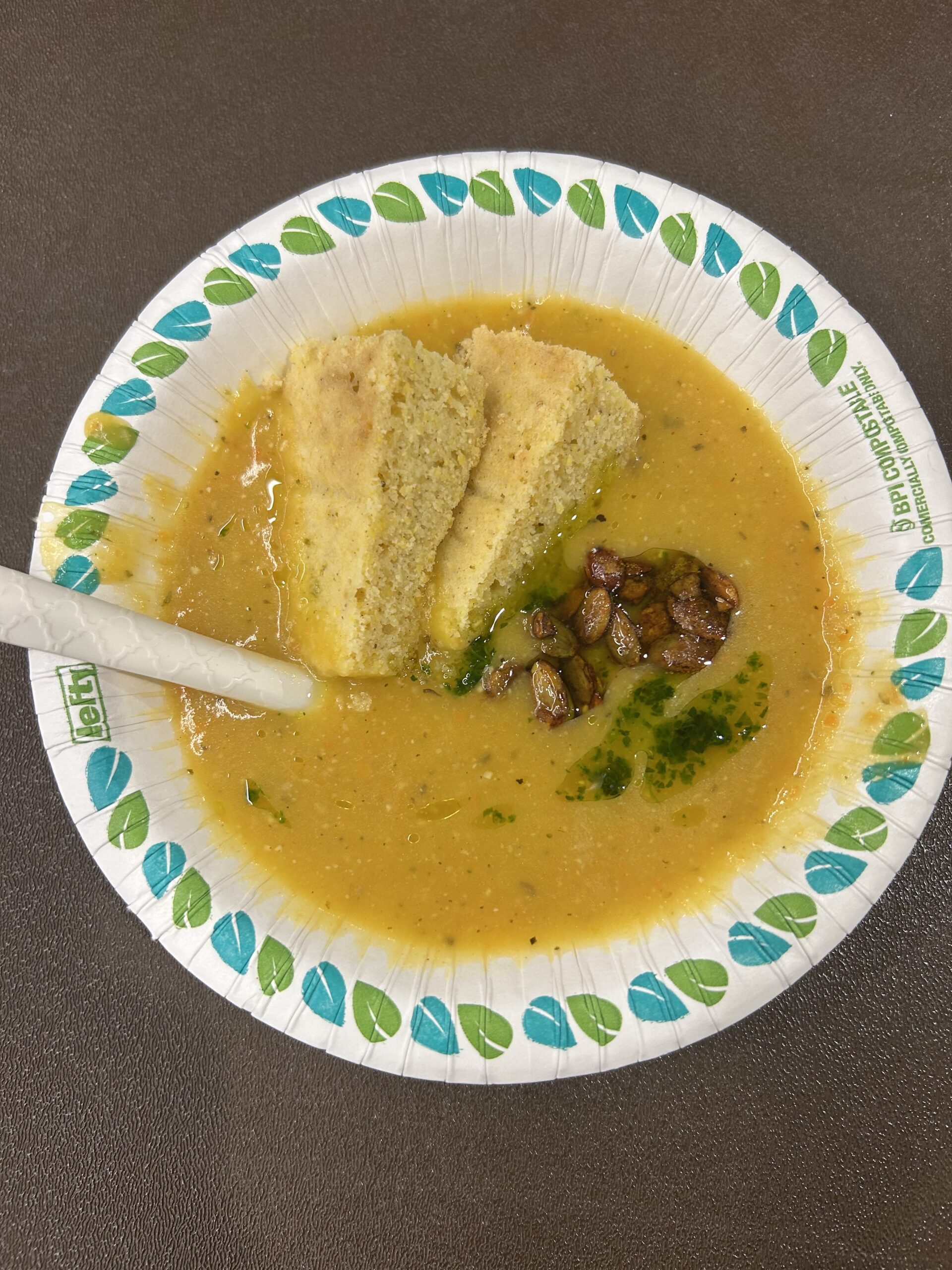

Refreshments prepared by Saul Schuster and Haley Christoff of Turtle Island Homestead added an additional layer to the event, highlighting the cultural significance of White Corn, a staple crop of the Haudenosaunee. Unlike sweet corn, White Corn is high in protein and has a lower glycemic index. Additionally, it can’t be eaten “green.” Rather, it needs to be dried out, shucked, and cooked in hardwood ashes to remove the hull. All of this is done by hand. Saul and Haley featured this staple crop in a butternut squash bisque with kernels of White Corn and cornbread, alongside a coconut chia pudding and sweetgrass and sage tea. Saul and Haley explained that White Corn represents resiliency, with heirloom seeds dating back at least 1,400 years in spite of European colonialist attempts to destroy the crop. “You destroy the crop, you destroy the people,” Saul said. Preserving and cooking with White Corn is a way of connecting with ancestors, past and present. Saul joked about meeting Haudenosaunee elders who will insist that they are making corn soup wrong! Everyone has their own recipes, which reveal personal and communal (hi)stories.

Through guided campus nature walks and embellishing canvas sling bags, students have the opportunity to develop their own relationship with these histories. For her project, Alexa Prouty ‘29 researched the environmental benefits of repurposing old buildings. On her sling bag, she paid homage to a dead tree that she saw on the guided walk with Trish. She learned that dead trees can be used as homes for animals, which she represented with a Labubu doll keychain. Far from detritus, the dead tree is still integral to the environment. This is in stark contrast with the human-made trash that pollutes the environment, which Alexa represented with glittery sequins at the bottom of the sling bag.

For Charley’s project, she researched the Red Oak, a tree indigenous to Turtle Island (North America) that has evolved to be highly adaptive to the effects of climate change. Although the Red Oak is not immune to the risks of climate change, it is known for its abilities to resist fire, retain water, and host a large community of insects, birds, and other animals. Charley reflected that the Red Oak could help us learn how to help ourselves – only take the resources that we need and leave the rest to other species in our community.

To learn more about the groups featured in this blog, see:

shared a variety of dishes cooked with ingredients from their farm and Indigenous

sources

written by Megan Lovely, Program Manager of Community-Engaged Learning