Student Research

Diary Links Centuries in Student Project

|

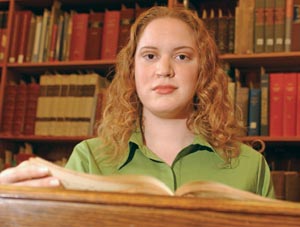

| DEAR DIARY: “It was like meeting a whole new individual,” says Kristi Martin ’04 of her research on a diary written by a young woman in the 1840s. |

Kristi Martin ’04 found a new friend during her senior year at Rochester. They shared many things in common—both were about the same age, both enjoyed writing, and both spent a lot of time in upstate New York—but an important difference separated them.

Martin’s friend, Adaline Lindsley, lived more than 160 years ago and might have remained anonymous much longer if Martin had not undertaken a student research project to study the young woman’s diary of life in rural Middlesex, New York, during the early 1840s.

“It was wonderful to bring her back to life,” says Martin. “She was just an ordinary person from the 19th century who would have been forgotten if not for her diary.

“It was like meeting a whole new individual,” Martin says. “In a way, I was able to gain a friend from the experience.”

Martin first “met” Lindsley during the College’s Meliora Weekend in 2003. As she and her older sister, Kimberly, waited to tour the tower of Rush Rhees Library, Martin saw the diary in a display case along with a notice that the library was looking for an intern who could transcribe the 140 pages of handwritten text.

The idea piqued the interest of Martin, who, as a student, drew from courses in history, English, and other humanities to design a major in American studies for herself. As she began deciphering the diary, she realized there was more research that she could do to flesh out Lindsley’s life and the history of her family.

The project eventually became Martin’s senior thesis. In addition to transcribing and annotating the diary, she also wrote a 40-page introduction, added an index, and collected photos and other historical material related to the diary.

For much of the last summer, the diary was back on display at Rush Rhees, this time in a case devoted to highlighting student work.

Martin, who hopes to pursue a career as a museum curator, says the research helped her appreciate not only the work that curators and scholars do, but also the lives of women in the 19th century.

Lindsley, who was the sixth child in a family of seven, had tuberculosis and

was housebound for much of her life.

In the period covered by the journal, roughly 1840 to 1843, the entries make

clear that Lindsley was a devoutly religious Christian who functioned as the

social hub of her family. She had a great interest in education and relied on

her brother, Thales, who was attending college during the time, to tutor her.

“I was surprised at how well educated she was,” Martin says. “She pretty much had a college education.”

In her research, Martin learned that Lindsley married a Methodist-Episcopalian minister named Joseph Cross in 1845 and traveled with him to New York City, New Orleans, and eventually to Lexington, Kentucky, where she died on Christmas Day in 1847. The couple’s stepson and daughter died earlier.

In 1854, Cross published a book devoted to his wife that included a biography of her and examples of her writing.

Martin suspects that Lindsley kept a journal recounting her life before the period covered by the one she studied, and that she must have continued to write because her husband drew on her work after their marriage in putting together his book.

Martin is confident that Lindsley had future readers in mind as she wrote. Given her tuberculosis, which often incapacitated her, Lindsley knew she was unlikely to live into old age.

Says Martin: “I think she would be happy that I have resurrected her, in a way, because she wanted to be known as a writer.

“She definitely had a future audience in mind.”