Alumni Gazette

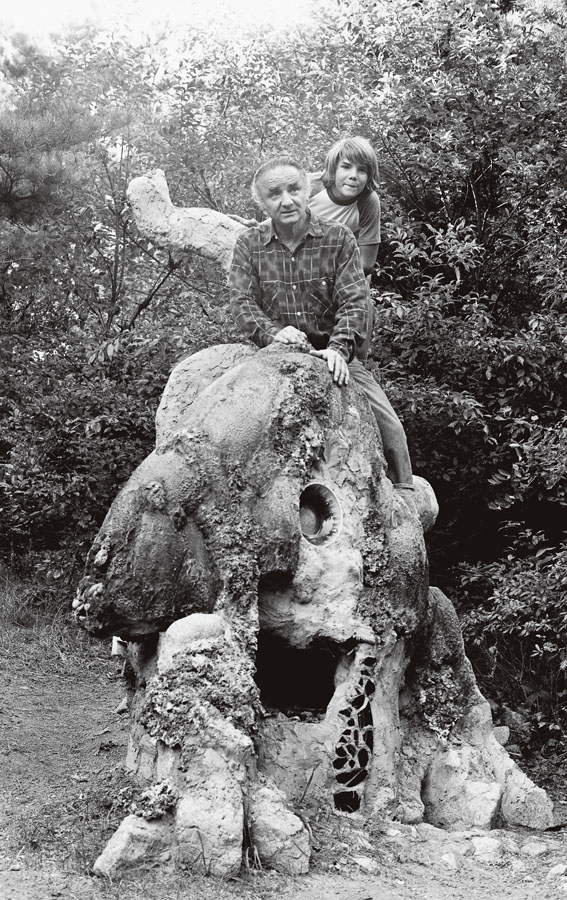

JUNK YARD: Father and son pose atop “The Monster,” a backyard sculpture the elder built from a coal stove and other throwaways. (Photo: Courtesy Sascha Feinstein ’85)

JUNK YARD: Father and son pose atop “The Monster,” a backyard sculpture the elder built from a coal stove and other throwaways. (Photo: Courtesy Sascha Feinstein ’85)A month or so after Sascha Feinstein ’85 released Wreckage: My Father’s Legacy of Art & Junk (Bucknell University Press), he received a welcome surprise: a four-page, single-spaced letter from his first creative writing teacher, the novelist Thomas Gavin, a professor emeritus at Rochester. It was “one of the greatest letters of my life,” Feinstein says.

Feinstein is now an accomplished writer himself—a poet, an essayist, and the codirector of the creative writing program at Lycoming College in Pennsylvania. Wreckage tells the story of growing up as the son of Sam Feinstein, a noted painter in the American postwar abstract expressionist movement who was also, according to his son, “a hoarder of monumental proportions.”

“The students he taught revered him,” says Feinstein. “Those who painted from his massive still lifes obviously knew he collected plenty of junk, but such facades eclipsed the many layers of things buried within.”

Feinstein’s mother, also an artist, died of cancer when he was in high school, leaving him alone with his father, whose hoarding consumed entire rooms of the home they shared. His father’s creativity bred physical and emotional destruction, a kind of contradiction that captivates Feinstein.

“As a writer, I’m most interested when opposites fuse with one another,” he says, adding that the overarching theme of Wreckage is “creativity married to destruction.” Yet, Feinstein finds that his father’s ideas about the creative process hold true, for artists, as well as for him as a writer.

“The artistic concepts that he taught for half a century—largely about making a canvas its own self-expression, with the fluidity of form and balanced colors creating a lifelike presence—still seem unassailable to me,” he says. “Each painting should inspire a journey for the eye that cannot be experienced in any other way except by viewing that painting. And, ideally, the viewer should hunger to return. Making an artistic statement that fully stands alone, regardless of medium, should be, I think, the goal of any artist. It’s certainly my greatest aspiration as a writer.”

Has he succeeded in this aspiration? Gavin found that Feinstein’s account of his father’s scavenging recalled Robinson Crusoe’s heroic efforts to rescue remains from his wrecked ship. But, as Gavin wrote in his letter to Feinstein, “Your superb portrait of [your father] in all his maddening, outrageous glory succeeds in many other ways that Defoe never imagined.”