Rock on, WRUR.

The radio station that began on a small corner of the University of Rochester’s River Campus, in the basement of Burton Hall, is now 70 years old.

What might be said about radio in general could also be said about WRUR: it has shown remarkable persistence. It survived the rise of television, thrived in the age of the VCR, and found new life in the 21st century, as first the internet, and then social media, threatened its eclipse.

There’s no question WRUR has made an impact. At times in its history, the impact has reached beyond the University.

In the fall of 1973, for example, WRUR was one of the only places in the Rochester area where you could follow the Senate Watergate hearings live (commercial television stations ended their live coverage in September).

In the 1980s, the station was part of a national heyday of college radio in which student deejays acted as tastemakers, elevating obscure bands to national and international stardom.

Consistently, however, WRUR’s deepest impact has been on the students who have participated in making the station run. They’ve received valuable professional training, to be sure. But that alone can’t account for the raw emotion that emanates so often from the alumni of WRUR.

“It was like heaven,” recalls Jim Carrier ’66, station manager in 1965. “WRUR was my college education.”

Last spring, outgoing general managers Carrie Taschman ’18 and Toby Kashket ’18 offered their own reflections. “A lot is ending,” Kashket said. “But we know that if we’re coming back to visit school, WRUR will be the first place.”

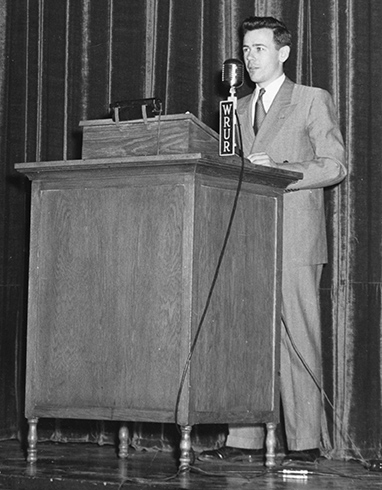

OPENING NIGHT: George McKelvey ’50, ’58 (MA) at the podium during WRUR’s first broadcast from Strong Auditorium. The World War II Navy veteran is widely credited with bringing college radio to Rochester.

They were, the Campus reported in January 1948, a “busy little group of men.” George McKelvey ’50, ’58 (MA), the World War II radio officer who first proposed a campus radio station and led the work to bring it to fruition. Glenn Bassett ’48, who helped on the business side. Daryl (Hugh) Albee ’50E, ’56E (MM) and Charles Adler ’50 who lined up the DJ's, musical groups, live broadcasts, and theatrical performers who would keep the entertainment going each evening from 7 p.m. to midnight at 640 on campus radio dials.

WRUR was student initiated and student run from the beginning. But the leaders of the University took note, as did those at the local station WHAM.

Originating on the River Campus at the College for Men, the station enlisted students at the College for Women as well. Dean Janet Clark of the College for Women joined in celebrating the station, comparing radio to aviation—rapidly advancing technologies that “belong to your generation.” Dean J. Edward Hoffmeister of the College of Arts and Sciences observed that commercial radio broadcasting had already become tired. “Radio needs new blood,” he declared. College students would provide it.

On the evening of February 10, 1948, a crowd gathered in Strong Auditorium. At 8 p.m., the station was formally launched with an announcement by a sophomore English major from Buffalo named George Toms ’50, ’51 (MA):

“WRUR is on the air.”

The 90 minutes that followed were a mix of celebratory addresses and performances by some of the University’s most beloved musical and dramatic ensembles. The 40-piece Eastman Orchestra, with Dorothy Merriam ’48E as soloist, performed the exuberant last movement of Mendelsohn’s Violin Concerto. “Sax-man” Kenn Hubel ’50 led a jazz quartet in a series of standards. The Women’s Glee Club sang, and the men’s dramatic ensemble, the Quilting Club, performed a satirical sketch.

Hubel still treasures the photograph of him and his band taken that evening. “The actual details of that opening night, I recall very few of,” he concedes. But he remembers McKelvey in particular as an extraordinary leader who brought something of lasting value to the University. “It was an operation of love that got off to a start that was originally shaky,” he says. “That’s the nature of any major achievement.”

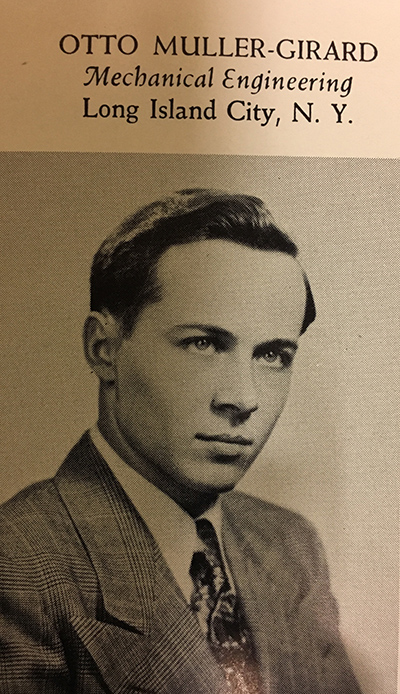

Otto Muller-Girard ’51, ’52 (MS)

Chief engineer, 1950–51

In its earliest days, WRUR was much more impressive as an outlet for cultural programming than it was as a technical feat. Otto Muller-Girard ’51, ’52 (MS) was a sophomore mechanical engineering major when he first tuned into WRUR.

“Terrible,” he says, recalling the reception.

He was no armchair critic. The station was located right inside his dorm, Burton Hall. He went downstairs to pay a visit. “I said, ‘Maybe I can help.’”

Muller-Girard had made a hobby of tinkering with radio as a high school student. Before he got to Rochester, he’d had a job installing and repairing television sets in New York City.

“It wasn’t like it is today, where you go into a store, you buy a TV, you move it up to the cable plug in the wall, and you’re ready to go,” he says. “You had to have an antenna out the roof or out the window pointing in the direction of the antenna of the station you wanted to receive. All the televisions in New York City at the time had different locations for their antennas. So really, it was a challenge. Which kind of station do you like? Because you can’t point at all of them—if you can point at any of them.” Customers were often frustrated. “People said, ‘I can’t get anything. Why buy the set?’”

When he joined WRUR, he saw it as an outlet for “pent-up design ideas” for transmitters. Among the problems he addressed was what WRUR station manager Ray Ettington ’51 still recalls as “the hum.” “The hum was a problem,” Muller-Girard concedes. “In our early transmitters, it was very prominent. When I came along, I could improve it, but I couldn’t really get rid of it. Operating on a frequency of 640 kilocycles—and transmitting over power lines in each building rather than over the air—were the roots of the problem.”

The students at the College for Women were growing frustrated as early as the fall of 1948 with the quality of the reception. Yet, “solving their weak reception and ‘hum’ problem was more challenging still, as access of male students to the basement transmitters was viewed with great suspicion and tightly controlled,” Muller-Girard recalls.

As chief engineer, Muller-Girard either built or rebuilt transmitters in four buildings: Burton and Crosby at the College for Men, and Monroe and Cutler Union at the College for Women.

SAX-MAN: A yearbook photo captures Kenn Hubel ’50, at right, leading his jazz quartet, from left, George Hart ’48, Ed Gordon ’52E, ’53E (MM), and Fred Remington ’50, during WRUR’s inaugural broadcast on February 10, 1948.

WRUR’s arrival came not at the beginning of college radio, but at a turning point.

“College radio actually goes back all the way to the 1910s,” says Scott Fybush, an industry analyst and editor and publisher of NorthEast Radio Watch. The first stations came out of Midwestern land-grant universities, which launched them as a way to bring up-to-date market information to farmers.

But as Harold McCarty wrote in the Phi Delta Kappan in the spring of 1939, college radio was by that time a shadow of its former self. McCarty was the director of WHA—a public radio precursor based in Madison, Wisconsin—and his article, “The Role of the College Radio Station,” was a rallying cry. In 1921, 168 educational institutions—mostly colleges and universities—had broadcast licenses. In 1939, the number was 25, “survivors of a severe trial period,” striving to be heard amidst a nationwide expansion of commercial radio.

The story, as McCarty told it, was that early college stations had arisen out of the intellectual curiosity of electrical engineering students. Once they had answered their questions to their satisfaction, the stations faded away.

The time had arrived for a new type of college radio station—one that would focus less on technology and more on programming.

“A busy little group of men”: In a photo from December 1947, from left, George McKelvey ’50, ’58 (MA), Charles Adler ’50, Daryl (Hugh) Albee ’50E, ’56E (MM), and Glenn Bassett ’48 were among the first students to propose and then run the campus radio station that would become WRUR.

At Rochester, a Radio Club met in the 1940s, and in the spring of 1946 declared a campus station as its aim.

As it turned out, however, the Radio Club’s broadcasts never achieved a wide audience, most likely because that was never the goal. The club served the purpose of “instructing interested members in the science of radio technology.” Headquartered in the engineering building (present day Gavett Hall, named in 1949), the club was mainly equipped to prepare students to pass the Federal Communications Commission examinations in radio code. In the spring of 1946, two years before WRUR emerged out of a series of electrical wires strung through the underbellies of campus buildings, students in the Radio Club were already schooling themselves in the relatively new technology of FM.

There is wide agreement—both in contemporary accounts and in present-day recollections—that WRUR came about due to the initiative of a single student: George McKelvey ’50, ’58 (MA).

Born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, McKelvey was drafted by the Navy following his graduation from high school in 1943. He served briefly as an aviation cadet, then as a radio officer at sea.

Just weeks before his death in 1998, McKelvey recalled that, “I had been reading a story in the New York Herald-Tribune about college radio stations. And it just seemed as though Rochester needed one.”

He was regarded as a skillful leader, remarkably effective at harnessing and focusing the enthusiasm of fellow students toward a singular goal. He was “an impressive guy,” says Hubel. WRUR was “really his endeavor, and he was able to find the people who could assist him.”

McKelvey majored in history and went on to earn a master’s degree in political science. During the semester of WRUR’s launch, McKelvey was elected to a leadership position in the national umbrella organization for college radio stations, the Intercollegiate Broadcasting System. He also headed the Empire Network, a partnership of New York state college radio stations that also included the stations at Cornell, Sampson College, Union College, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and St. Lawrence University.

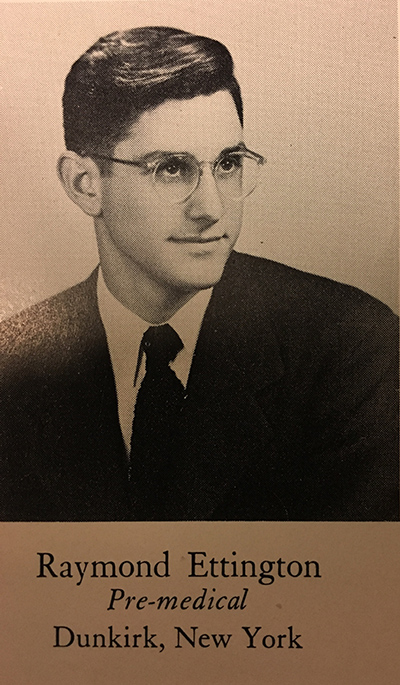

Ray Ettington ’51

Program manager, 1949–50

Station manager, 1950–51

Seventy years later, Ray Ettington ’51 still remembers sitting in the Todd Union lounge during his freshman year as the founders of WRUR were holding the first auditions for students who wanted to become announcers on the brand new station.

“They assigned them to read some scripts, but also to ad lib as though they were at a house fire,” he says. Ettington was already itching to be an announcer. But he would wait another year. “I thought, ‘I could never do that.’ Ad lib a whole thing like this? So I sat there listening.”

During his sophomore year, he applied for—and got—a role as a news reader. Every night at six o’clock, he read the news. “We would get two to three sheets in telegram form, all these strips, from the AP. And I would read five minutes of news,” he recalls.

It took a while for him to get comfortable in the role.

“When I started that, I was visibly shaking, I had such mike fright. It scared the hell out of me. Night after night, I’d go through this trauma. But after a year of that, if the AP [strips] didn’t arrive on time, I could ad lib five minutes. I completely lost my stage fright.”

From news reader, he became a public address announcer for football and basketball games, and a master of ceremonies for college banquets. A member of the dramatics group, the Quilting Club, he also participated in the role of radio actor on student performances broadcast over WRUR.

In his junior year, he was named program manager, and as a senior, he rose to the top role of station manager. There, he continued to pick up new skills. He found he excelled at selling advertising. To this day, he says, “I attribute my successful 36-year career in IBM sales and marketing to the selling and public speaking skills I learned at WRUR.”

In the spring of 1950, then station manager Tenney Johnson ’51, “reported that a drive will begin shortly to increase the quality and coverage of reception on the Prince Street Campus, as well as to enlarge the opportunities for feminine participation in the radio station’s activities,” according to the Campus. Ettington, along with program manager Tom Coyle ’52, “will help facilitate that move.”

Ettington still recalls his role in ensuring, for the first time, that the women students were not only heard as performers, but granted their own airtime, which they used to launch their first program, “Co-ed Corner,” in November 1950.

“This doesn’t sound like much today, but this was long before women were welcomed by the broadcast industry,” he says. “I’m very proud of that.”

Joseph Platt ’37, a professor of physics at Rochester during McKelvey’s years there, noted years later that establishing the station was largely a political task—and one at which McKelvey excelled. He “knew his radios,” wrote Platt following McKelvey’s death. “He also knew how to recruit and organize a group of undergraduates who wanted to help put Station WRUR on the air and keep it there.”

Recognizing McKelvey’s talents, the University called upon McKelvey to help develop networks of alumni, and with the merging of the Colleges for Men and Women in 1955, appointed him as the very first director of alumni relations. Two years later, Platt, having then moved onto become the first president at the brand new Harvey Mudd College, recruited McKelvey to become its director of development.

The earliest college radio stations, including WRUR, were carrier current networks, meaning that signals were transmitted through electrical wires—in many places strung through pipes—rather than antennae. Carrier current was a relatively low-cost approach, suitable to stations that broadcasted exclusively to a small geographic area—a school, campus, or hospital, for example. WRUR’s network would be somewhat more complicated, however, because the main transmitter in Burton Hall needed to connect to the College for Women’s Prince Street Campus, located about two miles away. It did so through a leased telephone line running to a booster transmitter installed on the women’s campus.

The network was designed to reach any radio within 200 feet of any electrical line in the system. But women on the Prince Street Campus complained of poor and uneven reception, with some buildings receiving no signal at all.

The complaints stung, given that the station was widely viewed as having the potential to foster unity between the two campuses. A series of articles in the Campus and the Tower Times throughout the fall 1948 semester traces the efforts of the station’s technical personnel to install new lines at the College for Women—and of the business and programming staffs to contend with the station’s first public relations challenge.

“The members of the staff of WRUR pledge their continued effort in the entertainment of the students of the University of Rochester and its colleges,” program manager Charles Adler ’50 announced in the semester’s opening broadcast on September 27. The women’s newspaper, the Tower Times, reported that business manager Dick Williams ’50 “announced that the aim of the technicians is perfection in reception and urges all WRUR fans to have faith until final adjustments are made.”

In spite of the ongoing technical challenges with the network, judging from the foreword of the 1949 Interpres yearbook, many students could barely contain their glee—or their expectations—regarding the significance of WRUR.

“Here is a new thought pushing aside stagnated thinking,” it read. “Here is a glimpse of the social progress we as individuals must stimulate. WRUR is a symbol of foresight and planning. It is probably a small step, but it is none the less great in its achievement, for it was born of a single student idea.”

The station seemed to be fulfilling one its core missions, to discover and help develop hidden talents among the student body.

“It is hoped by the leaders of the station that much latent talent among University of Rochester students may be found,” wrote a reporter in the Campus in January 1948. “Tryouts and auditions for programs may well discover many new voices and personalities on campus.” In April 1948 the dramatics group the Dandelion Players formed with the expressed purpose of broadcasting over WRUR. Meanwhile, the founders created a training program to take, as reported in the Campus, “the raw material (in the form of the student) and successively introduce him to the operations of all of the various departments and phases of radio station work.”

Yet, to the extent that WRUR was the voice of the University, it was, in its first several years, a male one. The growing staff of the station included women students, and all-women performance groups such as the Women’s Glee Club graced the station’s airwaves. But there were no live broadcasts on the Prince Street Campus. Instead, student broadcasters cut vinyl discs while on air in the Burton studio, making a recording that could be subsequently aired on the women’s campus.

In the fall of 1950, the College for Women won the first broadcasting spot of their own: a 30-minute show, aired every Tuesday evening at 9:30, called “Coed Corner.” Featuring five minutes of campus news and 25 minutes “filled by dramatic or musical sketches, featuring talented Prince Streeters,” the show was “written, directed, acted, and produced by the Women of the University,” a Times-Union reporter boasted.

The show, directed by Charlotte Allen ’51 (whom the Times-Union identified as a promotional director of WRUR), was an outgrowth of a concerted effort by station leaders to increase the participation of women students. By the time WRUR celebrated its fourth birthday in February 1952, the Prince Street Campus had its “own studio and console.” Three years later, with the merger of the two campuses, women would take the helm.

PRESENT AT THE CREATION: Ray Ettington ’51, right, and Otto Muller-Girard ’51, ’52 (MS) met while working as station manager and chief engineer at WRUR and have now reconnected after discovering that they live in the same Rochester retirement community. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

By the mid-1950s, WRUR no longer bore the weight of trying to unify two distinct campuses. In the fall of 1955, the College for Men and the College for Women united on the River Campus as a single entity, the College of Arts and Science.

During this same year, the new student newspaper—the Campus Times, a merger of the Campus and the Tower Times—celebrated the success of WRUR. The station had finally arrived. It was, by any measure, firmly established. A front-page feature celebrated the station’s success: “WRUR: A Big-Time Operation.”

For WRUR, a new studio accompanied the merger—one so superior to the makeshift operation in Burton Hall that the Campus Times declared WRUR now embarking on a new era, even after “a seven-year period of growth and expansion.”

For Joyce Timmerman Gilbert ’58, WRUR station manager during 1957–58, the change was especially stark. She recalls the Prince Street Campus studio, in Cutler Union, from her first year. “In Cutler, we occupied a windowless oversized closet,” she says. Atop a desk was a three-speed turntable, a rack of 33 1/3 records, a lamp, and a phone with a connection to the main studio. Given the University’s plans to move the women to the River Campus, there was no incentive to improve it.

The Burton Hall studio, while a cut above Cutler Union’s, was also rudimentary, consisting of little more than two turntables, a console, and a trio of microphones.

By contrast, the new Todd Union studio included three broadcasting studios, a news room, a business office, and a control room. Equipment included a brand new Magnecord tape recorder, a 16-inch Rek-o-Kut turntable, uni-level amplifier, and microphones—all state of the art for the time. A sponsorship from Levis' Music Store, a downtown destination for many Rochester musicians, brought a piano to the studio for live broadcasts. “WRUR this year boasts some of the most modern equipment and facilities of any college radio station,” Robert Mates ’57 reported in the Campus Times. “The large studios surpass the facilities of many of the city’s commercial stations.”

The merger of the two campuses and the new studio together brought forth a burgeoning of new programs. “Symphonic Studies," led by Judy Kantack Temperley ’57, a program of “light piano favorites,” by Mary Luft Fenwick ’56, and piano improvisations by Alan Kohan ’55E, ’56E (MM), were just a few.

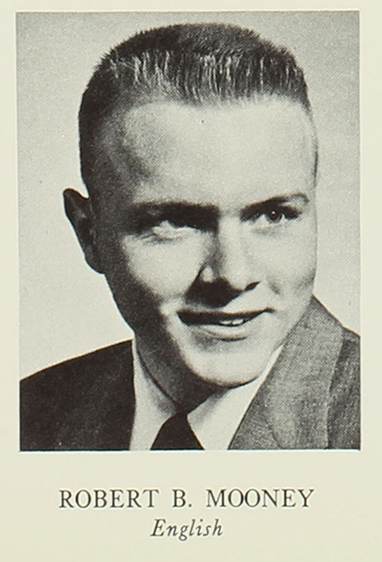

CAMPUS CELEBRITIES: “Uncle” Bob Mooney ’60 was the host of the Tuesday evening light jazz program “Moonglow Show" and an early DJ personality.

New student groups arose just to take advantage of the opportunity the campus radio station promised. WRUR Players’ Workshop, for example, formed in the fall of 1955 and performed plays monthly on a show called “Curtain Time.”

There was also more coverage of campus news through regular forums that drew students, faculty, and administrators together to discuss issues of common concern.

Meanwhile, other student organizations turned to WRUR to share their news and promote their events. A WRUR promotion director collected “spots” written by club representatives to be read over the air.

With about 80 student engineers, announcers, and broadcasters working under the supervision of a governing board, WRUR was the largest extracurricular activity on campus.

While many WRUR staffers worked behind the scenes selling advertising, collecting sponsors, and providing technical assistance, the station also gave rise to a new type of campus celebrity: the DJ personality. An early example was “Uncle” Bob Mooney ’60, whose “Moonglow Show” featuring light jazz aired on Tuesday evenings. In the spring of 1958, Mooney inaugurated a weekly WRUR column in the Campus Times in which he brought a bit of that personality to print, pumping up colleagues (“Jim Hagadorn’s many guests on the ‘Monday Morning Show’ will soon force us to knock out one of the station’s walls . . . How can you get people up so early, Jim?”), and cajoling listeners with highlights of the coming week.

Notably, women became instant leaders in student journalism with the merger: Ann Dalrymple ’56 took on the role of WRUR station manager and Sally Miles ’56 rose to editor of the Campus Times.

Dalrymple was named station manager in March 1955 and continued in the role for most of the 1955–56 academic year (a new leadership slate was selected again in March 1956). Practically speaking, her appointment made a lot of sense: she had been the assistant program director the previous year on the Prince Street Campus. But still, it was remarkable.

Following the integration of men and women, “there were many questions about what the resulting entity would look like, feel like, be,” says Gilbert, who took over as station manager in 1957, marking another point of pride for women students. Nonetheless, she adds, “In many respects, power remained in the former College for Men.”

On the Prince Street Campus, women were visible and influential leaders. Gilbert, along with WRUR station-mates Nancy Kelts Rice ’58 and Deanne Molinari ’58, all recall powerful role models such as Margaret Habein, dean of the College for Women, and Ruth Adams, a faculty member in the English department. Under their tutelage, women students thrived.

IN CHARGE: From left, Gordon Spencer ’57, ’63 (PhD), Dave Anderson ’57, ’63W (MA), Barry Robinson ’57, Ron Coplon ’56, and Ann Dalrymple ’56, seen in a Tower Times article from March 1955. Dalrymple has just been named station manager for newly unified WRUR at Todd Union.

“On the women’s campus, women had the opportunity to take leadership roles,” recalls Rice. For a time—at WRUR at least—women leaders held their own. Gilbert, for example, recalls being invited to meet with then station manager Jack Barber ’57 and another male WRUR officer. They asked her if she’d be interested in becoming the station manager the following academic year. “To this day, I wonder why they chose me, and how decisions were made. Obviously, my answer was yes.”

After Gilbert’s graduation, women continued to be involved with the station—but not, for the most part, as officers. Rice, Molinari, and Gilbert speculate as to why.

“There may have been a decreasing emphasis among women students on leadership roles to ‘get along’ with men students. And without strong leadership interested in women’s roles, their presence in these roles faded away,” says Rice.

Gilbert concurs. “The old pattern began to reassert,” she says.

Molinari stresses the progress the women still made. “Women had a strong presence in leadership roles in student government, as well as various publications,” she says. It wasn’t perfect, she adds, “but the ethos did begin to change with our arrival on the River Campus.”

Joyce Timmerman Gilbert ’58

Station manager, 1957-58

Joyce Timmerman Gilbert ’58 got her introduction to WRUR in a closet-sized, makeshift studio in Cutler Union. By her senior year, she was station manager ensconced in a new, multiroom, impressive-for-its-time studio in Todd Union on the River Campus.

In July 2018, Molly Robins ’20, a WRUR DJ and chief engineer major from Culver City, California, opened the doors of WRUR’s Todd Union studio so that Gilbert could take a peek for the first time in 60 years. Gilbert, who lives in Rochester, shares her recollections and reactions.

Jim Carrier ’66

Station manager, 1965

In 2016, Jim Carrier ’66, DJ (“The JC Show”) and 1965 station manager, shared recollections of his work on WRUR, as well as thoughts on his love of radio, with Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian.

“I’ve had a wonderfully productive and adventurous life,” he wrote, “and it all began in the basement of Todd Union.”

Carrier was a leader in bringing WRUR-FM on the air. After graduating from Rochester with a degree in psychology, he migrated to central New York, where he became a newscaster for WTKO in Ithaca. He spent most of the 1970s as a writer, editor, and correspondent for the Associated Press. Following a five-year stint as managing editor of the Rapid City Journal in South Dakota, Carrier became a columnist, project writer, and roaming correspondent for the Denver Post in 1984. He remained at the Denver flagship paper until 1997.

Carrier is the author of 12 books. His work has also appeared in National Geographic, the New York Times, and the 2010 Best American Science and Nature Writing anthology.

In recent years, Carrier has taken to film, producing documentaries and multimedia materials for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Growing up on a chicken farm in the Finger Lakes in the 1950s, I first learned of the world over the horizon on a little brown radio that my mother kept on a red breadbox in the kitchen. After school and chores I would sit on a stool, as she made supper, and listen to 15-minute radio dramas. They included “Sky King” and the “Lone Ranger.” I also remember hearing Santa Claus reading letters that we mailed to the station, listing the toys we hoped to get. It was quite magical. It was also a fountain of imagination.

As I became a teenager, and rock ’n’ roll began to edge out the music of Sinatra and Rosemary Clooney, the music my folks sang and played, I was able to buy a couple of 45 rpm records and pretend to be a DJ. I practiced for hours timing the intro to finish just as the singing began. That, I thought, was the height of professionalism.

I arrived at the University of Rochester as a pre-med student in the fall of 1962. It was likely during my first trip to the mailboxes in the basement of Todd Union that I discovered WRUR. Maybe there was an open house, but I walked in, and, quite literally, got sucked into a world that, until then, had only been in my imagination. The huge record library, the studios, mics, a workbench littered with wires and tubes, sofas covered with empty pizza boxes, all peopled by nerds, geeks, misfits and dreamers: It was heaven, and I really never left.

My earliest memory is from November 22, [1963] racing to the station after our classes were abruptly dismissed, and seeing UPI wire copy of [President] Kennedy’s assassination stuck to the station door windows. Students were crowded around reading the latest. Stepping inside, helping out, I felt I was part of history. I still have one of the bulletins.

In time, I learned the ropes, had my own show — “The JC Show” — learned production techniques, created stories and illusions, and an audition tape that I sent to WBBF, the No. 1 rock station in Rochester. They hired me as a fill-in jock for vacationing DJs, most often 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. on Saturday night. My fellow “Busy Bees” included Jessica Savitch and Jerry Fogel. Periodically, using my student status, I’d visit some famous DJ as he worked, notably Cousin Brucie on WABC in New York.

At WRUR, meanwhile, I became station manager, and put the FM station that [1963 station manager] Bill Claiborn ’64 and others had started, on the air in 1966. Putting WRUR on the FM dial 50 years ago was also very important to the University, although I doubt they understood its significance. For the first time, a real radio station broadcast to the city from the campus, one run by students who rose to professional standards. Today, of course, it is also a public radio outlet.

By the middle of my junior year, I was at a crossroads — radio or medicine. Friends stuck a “Where is JC?” arrow on my dorm door. You could swivel it between “WRUR” and “Strong Hospital,” where I worked as an orderly. Radio won, and I graduated in 1966 with a BA in psychology.

But WRUR was my college education — the most important thing I got out of four years at the U of R. It was here that this country kid began to find his voice. I’ve had a wonderfully productive and adventurous life, and it all began in the basement of Todd Union.

By 1960, WRUR was operating in an environment of heightened expectations, yet still struggled with technical infrastructure and capacity. In the spring of 1962, station manager Leo Zabinski ’64 told the Campus Times that, in CT’s words, the station had gone “as far as it can with AM carrier current.”

On Sunday evening, March 6, 1966, at 7 p.m., WRUR launched its first FM broadcast. Now at 90.1 on the FM dial and broadcasting with 10 watts of power, WRUR-FM reached beyond the River Campus, extending outward to within a 5- to 10-mile radius.

Why did it take so long? The station would be reaching well beyond the University—and becoming subject to regulation by the Federal Communications Commission. Before WRUR-FM could go on the air, the station’s leaders had to apply to the New York State Board of Regents, the University administration, as well as the FCC.

Much of the process was overseen by Jim Carrier ’66—host of an eponymous show on WRUR, the station’s regular columnist at the Campus Times, and the station manager in 1965.

Late in the fall 1964 semester, Carrier sat down to lunch with local station WBBF’s general manager, Robert Kieve, to make what he thought would be a clear-cut case for the WRUR’s readiness to broadcast to the larger community under FCC oversight. As Carrier explained the following week in his regular Campus Times column, “Carrier Waves,” Kieve had instead posed to him some clarifying questions about the goals and aims of WRUR.

Who was the audience for WRUR now? Who would it be for WRUR-FM?, Kieve asked.

“I mumbled something through my whiskey sour about college-level people, professors, and civic-minded individuals, but way down inside, I knew that I hadn’t hit the nail on the head. In fact, I hadn’t even picked up the hammer,” Carrier wrote.

WRUR had surveyed students about their listening preferences since its first semester on air. In fact, it was a requirement of the station’s membership in collegiate radio’s umbrella group, the Intercollegiate Broadcasting System.

But Kieve’s questions inspired Carrier to spearhead a more comprehensive survey—one that would dispense with assumptions and “once-and-for-all find out” what students were listening to and use the results to shape future programming.

The survey revealed that folk music enjoyed wide popularity, and accordingly, folk programming got a boost. Two folk DJs in particular, James Lemkin ’68 and Phil Zimmerman ’66, brought a global element to their shows. As host of “Folk Music of Africa,” Lemkin played music and invited guests, including African students at the University, to talk about the music and the continent. Zimmerman aired music and interviews by traditional folk music artists “from this country and around the world” on his show, “Trip O’er the Mountains.”

By the mid-1960s, “rock and roll” was widely considered the music of the younger generation—and in 1965, partly as a result of the student survey, WRUR began broadcasting the genre for the first time.

Those born in later generations might assume the students had clamored for it. But Carrier revealed a more complicated picture: a sizeable group of students were listening to rock and roll. But would they want rock on their treasured college station?

“Do me a favor,” he wrote in “Carrier Waves.” “Ask yourself if you like Rock and Roll. Chances are you will say no. Do you muster all the grownup college-man seriousness to tell of your appreciation of classical music and jazz, but shrink away from the words Rock and Roll? . . . Mr. College Man, are you afraid to admit your craving for Rock and Roll?”

WRUR-FM signified a certain gravitas, underscoring the significance of the station as an educational and cultural enterprise—cultural in the highbrow sense, bringing to area listeners music either widely regarded as serious, or at the very least, broadly popular, as in the case of standards.

Consistent with its role as an educational resource, the FM station would carry no ads. It would broadcast classical, jazz, popular standards, and other varieties of music, along with news and discussions. In order to comply with the FCC, WRUR-FM would be owned by the University, rather than by the Students’ Association, as it had before.

Meanwhile, the AM station would continue to broadcast, free from the FCC. It was considered a training ground for DJs aiming for FM. But it was also a platform for experimentation. Anyone with any lingering reservations about rock and roll could rest a little easier knowing that, in the near term at least, the genre would be confined to AM.

While WRUR had always covered campus news, WRUR-FM did so in an atmosphere of higher stakes. In the late 1960s, the station had to contend with multiple campus controversies. In 1967, WRUR faced criticism among some students when it interrupted a broadcast of the show “Accent on Religion” with University chaplain Peter Holdorf. Draft resistance, which was illegal, was a topic on the show. Did the discussion constitute advocacy of an illegal act, a violation of FCC regulations? The station’s executive board said it did.

The program “was not a discussion, but a monologue; only opinion in favor of the Spring Mobilization was represented,” the board wrote in a letter published in the Campus Times.

One critic noted that WRUR had recently run live coverage of a speech on campus by the Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary, during which Leary had openly encouraged the use of the illegal hallucinogen LSD.

But the board held firm: “Educational broadcasting is not an excuse to provide a sounding board for certain selection programmers to expound their philosophies under the guise of ‘freedom of speech.’”

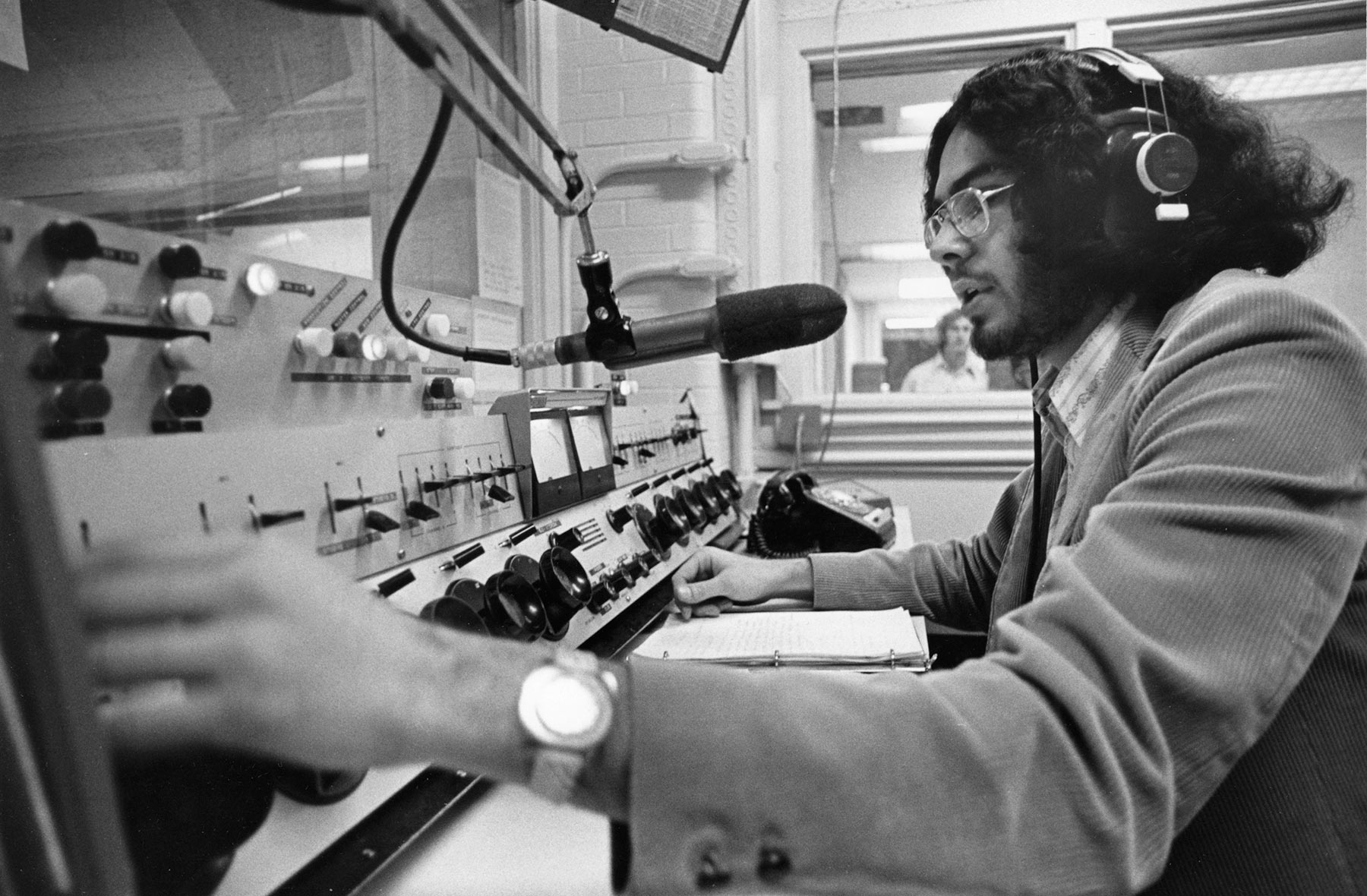

By the 1970s, WRUR was thriving in what would become a golden age of college radio. In 1971, Billboard magazine estimated there were 450 college radio stations across the country.

By 1975, that number had grown to more than 600. And students were listening in droves.

“About 40 to 50 percent of all college students listen to their campus radio stations,” Billboard reported. “That’s a claim very few commercial stations can make.”

The golden age would extend through the heyday of Madonna and Michael Jackson in the 1980s—though neither artist would be heard on college radio, which was widely credited with “discovering” the musicians and groups who were rarely, if ever, heard on commercial stations.

At the onset, the growing popularity of college radio was partly due to advances in consumer electronics. “If you were working at the college FM station in 1965, most of the kids in the dorms wouldn’t have had FM radios, and they certainly wouldn’t have had them in their cars, so to a certain extent you were talking to nobody,” says Scott Fybush, a radio industry analyst and editor and publisher of NorthEast Radio. “You go a decade forward to 1975, and everybody’s got an FM radio, and everybody can tune to the bottom of the dial and hear you.”

At the onset, the growing popularity of college radio was partly due to advances in consumer electronics. “If you were working at the college FM station in 1965, most of the kids in the dorms wouldn’t have had FM radios, and they certainly wouldn’t have had them in their cars, so to a certain extent you were talking to nobody,” says Scott Fybush, a radio industry analyst and editor and publisher of NorthEast Radio. “You go a decade forward to 1975, and everybody’s got an FM radio, and everybody can tune to the bottom of the dial and hear you.”

But there’s also no doubt that cultural changes played an outsized role. Adds Fybush: “The musical scene was exploding all around you, and the culture was exploding all around you.”

All of these changes were apparent at WRUR, as the station entered a two-decade period of continued transformation and growth.

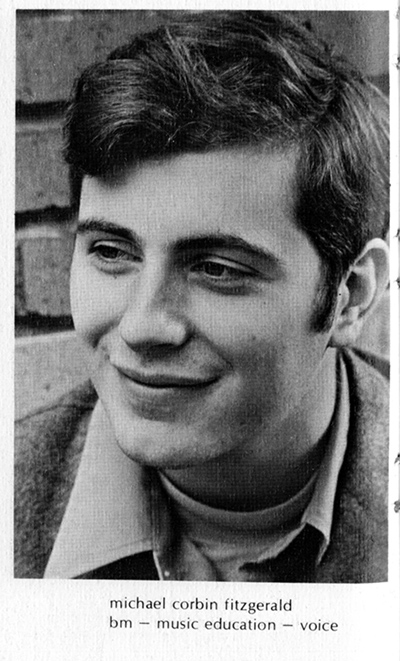

Mike Fitzgerald ’70, ‘70E

Disc jockey

Mike Fitzgerald ’70, ‘70E majored in voice and trumpet at the Eastman School of Music and education at the College. The Poughkeepsie, New York, native stuttered as a child and listened to radio shows religiously growing up to “mimic the DJs and improve my voice.”

Fitzgerald hosted several “Top 40” countdown shows when he joined WRUR. That experience led to a 44-year career as a radio disc jockey, including 30 years in New York City (he also hosted a morning show with Micky Dolenz of the Monkees). While at WHN in New York, he won a Billboard Radio Award for best on-air personality in country music in a major market.

“You never know what will happen,” says Fitzgerald, now a freelance game designer and radio consultant in Lafayette, Colorado. “I go to college to be a musician and end up training for a career as an on-air personality.” WRUR paved the way, he says.

“It provided a great way for me to work on smoothing out my speech and gain confidence,” he says. “Without WRUR, I never would have been an on-air personality.”

Even before the ’70s began, the music of young America permeated the airwaves at WRUR.

“We played everything from the Beatles and bubble-gum groups, Motown groups like the Temptations, the Four Tops, and the Supremes, to early metal groups like Iron Butterfly and Steppenwolf,” says Tom Bartunek ’70, who hosted shows all four years he was at Rochester and was program manager his junior year.

WRUR featured soul beginning in the mid-1960s, when Bartunek and Bruce Hammer ’69 hosted nightly shows, playing everything from stars like James Brown, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, and Ray Charles, to lesser-known acts like Ruby Andrews, Little Milton, Rex Garvin and the Mighty Cravers, the Sand Pebbles, and Al Green, before he became a popular 1970s crooner.

“Soul was just on late in the evening,” says Hammer, who was station manager his senior year. “In those days, that was 'Todd break time', when students would wrap up studying or take a break and grab a snack at the student union. So, we had a captive audience with the speaker outside the studio in Todd.”

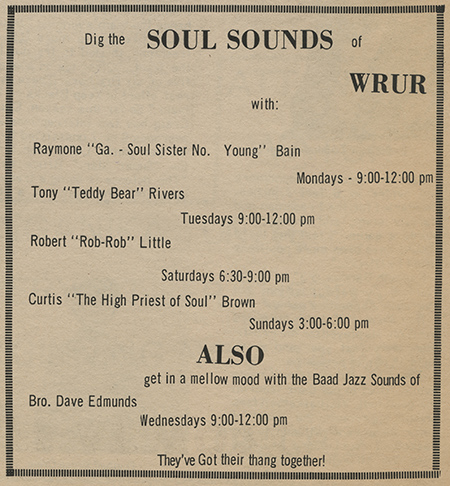

DIG THE SOUL SOUNDS A 1972 ad from the Campus Times.

The first African-American student to host a soul show was Jackson Collins ’71, a New York City native, a member of the newly formed Black Students Union, and a star on the men’s basketball team.

“His stature around campus attracted a lot of other black disc jockeys,” says Bartunek recalling Collins, who died in 2006.

By 1977, another genre would dominate the music scene—one that the DJs at WRUR were reluctant to acknowledge.

“The music played at WRUR is not similar to conventional AM radio,” the Campus Times reported. “The disco duck has yet to quack its way into the hearts of our DJs.”

WRUR had been broadcasting on a scant 12 watts throughout its history, reaching only those living within a few miles of the River Campus. But early in 1970, the FM station announced it would begin broadcasting in stereo at 20,000 watts, making it just the third stereo station in Rochester and extending its reach throughout Monroe County and beyond.

When the first stereo broadcast took place on February 6, 1970, the occasion was marked by a level of acknowledgment that recalled the station’s inaugural broadcast in 1948. City of Rochester Mayor Stephen May welcomed WRUR into the community. University president W. Allen Wallis extolled the station as “an exclusively student enterprise,” which had proven to be an enduring asset to the institution. And Dean Kenneth Clark noted that WRUR reflected the College’s effort to offer opportunities that were “not a shadow experience of the real world, but an actual, participating experience.”

On the evening of February 6, 1970, a sign-on by former station manager Jeff Portnoy ’70 kicked off WRUR-FM’s inaugural broadcast in stereo at 20,000 watts.

With WRUR-FM now reaching all of Monroe County, the 50-minute broadcast was a celebratory occasion.

University President W. Allen Wallis, Rochester Mayor Stephen May, and Dean Kenneth Clark of the College of Arts and Sciences all offered their thoughts on the air, striking a unifying theme. WRUR would now be, in Wallis’s words, “an exceedingly useful link bringing together the University of Rochester, the City of Rochester, and the Greater Rochester area.”

Students’ Association treasurer Gerald Katz ’70, struck a similar note, while presenting a detailed account of the work that went into bringing the FM stereo station into being.

The inaugural broadcast offered a rich overview of the station’s programming, as newly appointed station manager Alan Feinberg ’71 introduced a succession of DJs who, one after the other, pitched upcoming programs by offering musical excerpts and bits of commentary on folk, jazz, “progressive rock,” Top 40, classical, and soul.

In his view, the students had done an extraordinarily job. “I believe that the people of the community of Rochester are going to be astonished as they listen to this station,” he said. “If you tune it in accidentally, you will not believe that you are listening to a station that is run as an extracurricular activity of students at the University of Rochester. You will believe that you are listening to anoter one of the professional stations in the community.”

But this time the fanfare was short-circuited. Several chemistry professors in Lattimore Hall, adjacent to the station’s headquarters in Todd Union, noticed that equipment vital to their work was inoperative while WRUR was on the air. Professor Andrew Kende called the WRUR signal “electromagnetic pollution” and estimated that 17 lab rooms in Lattimore were unusable, and thousands of dollars in unfilled contracts were being lost.

On February 17, just 11 days after its 20,000-watt transmitter debuted, WRUR-FM announced it would make an unusual request to the FCC to drop its power to 970 watts, a level which would not interfere with chemistry experiments.

In 1973, when the chemistry department moved to Hutchison Hall, several buildings away from Todd Union, students at WRUR hoped to return to 20,000 watts. But some faculty members remained uneasy about the station’s power, and WRUR remained at 970 watts. It wasn’t until 1993 that the station would raise its power to 3,000 watts by moving its transmitter atop the Hyatt Hotel in downtown Rochester.

AND NOW IN STEREO: Top row, from left, Rod Cowan ’70, Jeff Portnoy ’70, and Alan Feinberg ’71; and standing, from left, Andy Hanushevsky ’72, Peter Zadarlik ’74, Bob McAvoy ’66, an unidentified participant, and Phil Fenster ’71 proudly accept the delivery of the station's new FM transmitter on October 30, 1969.

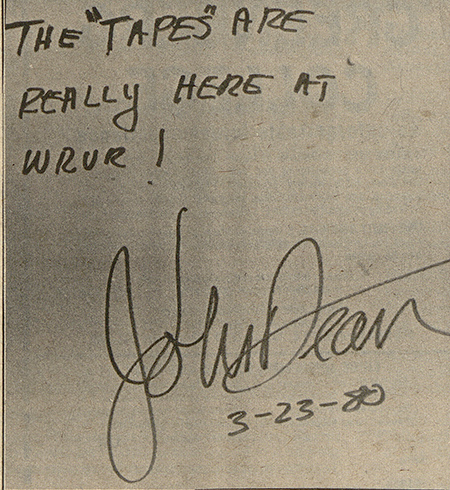

BREAKING NEWS: Watergate figure John Dean III left his mark (and his autograph) when he visited campus in March 1980.

Students hosted daily news programs and weekly shows like “Rochester Political Scene” and “Science in Rochester.” They took their role as journalists seriously.

“We tried to cover it all,” Bartunek says, “including our take on the killing of Kent State students [by National Guardsmen] in 1970 on a day that our classes were canceled for a campus-wide day of discussion and debate.”

WRUR also would cover a student strike on the River Campus in 1969, broadcasting live many meetings between students and the administration.

Throughout 1972, WRUR ran a show called "Path to the White House” that featured coverage of state primaries leading to that November’s presidential election. In September 1973, the station began live broadcasts of the Senate Watergate hearings after the three major commercial television networks decided to end their live coverage of the proceedings.

In the early 1990s, WRUR remained an important venue for state and local office-seekers to gain exposure. Students with WRUR News hosted conversations touching on hot-button issues of the day, including taxes, abortion, drugs, and the death penalty, and delving into the details of policies and their implementation.

This clip from 1990 features Ethan Corona ’94 interviewing Pierre Rinfret, the Republican challenger to incumbent New York Governor Mario Cuomo.

Election nights were major events at WRUR. The station would send three crews out to Democrat, Republican, and Board of Election headquarters and report on returns from late afternoon until early the following morning.

“It was a thrill, and we did a pretty damn good job,” says Steve Alperin ’83, who hosted shows all four years at Rochester. “Election night was always a big deal for us.”

The custom continued well into the 1980s. According to Adam Konowe ’90, WRUR was given the same access as the local commercial TV or radio stations. “Each media outlet had a table at a party house, with a landline phone on the desk, and a mixer and microphone next to the engineer,” he recalls. “We would do updates all night.”

Konowe said he was involved in WRUR “from Day One,” and this fall his daughter, Celia Konowe ’21, became a disc jockey on The Sting, WRUR’s online station.

Because it operated under FCC rules, WRUR-FM had to justify that it deserved to keep its license, which was renewed every five years.

“We had to prove that we served the community, and not just ourselves,” says Dan Luna ’88, chief engineer and later general manager.

In addition to its strong election night coverage, WRUR’s FM channel was a major source of University news, airing campus meetings (sometime live, sometimes on tape), sporting events, a sports call-in show, and live broadcasts of operas performed in Strong Auditorium, while hosting discussion forums about topics of interest on the River Campus and call-in shows with University administrators.

In the fall of 1985, when misinformation about the transmission of AIDS abounded, WRUR’s Lisa Grunberger ’88 hosted an evening call-in show with three guests: Sue Cowell, a registered nurse and nurse practitioner and AIDS educator working with the Monroe County Health Department and University Health Services; Mark Siwiec ’87, cochair of the Gay and Lesbian Association at the University; and William Valenti, ’76M (Res), a medical doctor specializing in infectious diseases at the Medical Center.

The broadcast shows the role of WRUR in bringing expertise at the University and in the Rochester area before the public; and gives a sense of the University’s role in AIDS treatment, prevention, and education in the early years of the disease’s spread.

In 1973, a nightly 15-minute local news show was established on the FM dial, while WRUR-AM aired a Sunday afternoon show called “Two Hours of Lunacy” which ran the gamut from shows about local politics and news from the River Campus to the world premiere of a new opera called L’amour Meshugeh and a special called “The World of Woody Allen.”

Ron Gerber ’90, ’92 (MS)

Disc jockey

When Ron Gerber ’90, ’92 (MS) was a graduate student in the early 1990s, he debuted a show on WRUR called "Crap From The Past"—a title suggested by a former WRUR engineer.

He had been the AM program director in 1989. With the FM station acting as an antidote to commercial “Top 40” Radio, AM lost a bit of its luster. “I staked out my musical claim by playing older pop music, with plenty of disco and new wave from the late 1970s and early ‘80s,” Gerber says. “This was a very odd thing to do in the late ‘80s. College radio scoffed at everything pop. And that left me thumping away to my own amusement.”

By the early 1990s, tastes may have shifted.

The most popular songs played on the show in 1992 included “Come On Eileen” from Dexy’s Midnight Runners (1983), “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees (1978), “The Safety Dance” from Men Without Hats (1983), “Whip It” by Devo (1980), and “Funkytown” by Lipps Inc. (1980).

“The response was overwhelming,” he says. “Within three months, I had so much phone response that the show was 100 percent requests.”

In hindsight, Gerber attributes the show’s success to “luck and timing.”

“The concept of ‘retro’ was about to go mainstream,’’ he says. “I was lucky enough to be playing older music on the radio just before everyone else did.”

To archive his shows, Gerber would record the shows on hi-fi VCR tape. “They were audiophile’s dirty little secret,” he says. “They could record six hours uninterrupted on a $2 tape, in extremely high fidelity. I’d start the VCR recording at home, go do the show, come home and then stop the tape.”

The show continued after Gerber received his MS in optics in 1992.

“It has followed me for 26 years and counting,” he says. “I lugged the show around with me as I moved city to city, through graduate school and other jobs. I even brought it back to WRUR in 1996–97 when I worked for Eastman Kodak.”

He has hosted Crap from the Past on KFAI-FM in Minneapolis since 1998, where it still airs on Friday nights. The show has run on stations in New Zealand, Germany, England, Singapore, and Brazil. In 2017, Gerber wrote a book about radio titled Between The Songs: A Step-by-Step Guide to Creating Radio Magic, or: Stuff I Learned from Hosting Crap From The Past for Twenty-Five Years.

The station also was a fixture at an annual dance marathon from the Louis Alexander Palestra which started in 1974 as a 48-hour charity fundraiser. Engineers snaked cables from the Palestra to a nearby dormitory and set up a common area, then sent a line over to Todd Union and broadcast live.

The DJs didn’t just play music at the marathon; they danced to it.

“My freshman and sophomore years, I was one half of the couple representing WRUR in the dance marathon,” says Jacqueline Volin ’87, WRUR’s FM program director during her senior year. “Either I was DJing or my friends were, and that was a nice thing to have over a long weekend.”

In the spring of 1974, the Student Activities Board inaugurated an annual tradition: the Dance Marathon, a charity fundraiser in which contestants sought sponsors as they danced to live music in the Palestra over a 48-hour period—with only 20 minutes rest every two hours and two three-hour sleeping periods.

WRUR broadcast the event live each year.

In April 1989, WRUR’s broadcast included a 2 to 4 a.m. set by a band called Calvin and the Night Rockers, who delivered a rousing program covering tunes from Stevie Wonder (“Superstition”), Eric Clapton (Further up the Road”), Aretha Franklin (“Respect”), and more.

The band ended its first hour with the 100th song of the event: “Knock on Wood,” the 1966 hit by Eddie Floyd that made it to number one on the Billboard R&B charts, and which disco diva Amii Stewart covered in 1979. Listen to the first hour of the set here.

Luna says WRUR played “many different genres” of music.

“For myself, I couldn’t stand most of it and was content to watch the needles bounce up and down in the transmitter room,” he says. “I liked jazz and classical, but that was about it. But I understood that the outlet provided by college radio gave new music a chance that commercial stations couldn’t give.”

Volin says one emphasis at the station during her time as FM program director was alternative rock—“though at the time, we just thought of it as college radio music.”

That’s because college radio stations, for the most part, brought the alternative genre into being—and eventually into the mainstream.

“We played music from a lot of bands from overseas, especially from the UK, who eventually became well known,” she says. “I was also a huge R.E.M. fan, and they’re the best example I can name of a band that made it big thanks to college radio.”

HEY DJ: Jacqueline Volin ’87 spins records during the 1986 summer picnic.

Volin says her format was an “open” one.

“By playing lots of singles by many bands, college radio stations like WRUR gave exposure to a lot of bands whose music wouldn’t have had airplay otherwise. We played anyone whose music we thought was cool.”

The list included everyone from the Soup Dragons and Cassandra Complex to Chameleons, Politburo, and Cactus World News.

Not exactly Cyndi Lauper or Duran Duran, but that was the point.

Likewise, Alperin, who hosted radio shows all four years at Rochester, says WRUR’s policy was to let the DJs work independent of a set format and with little regard to the hits of the day.

“Everybody had their own thing, and we really didn’t do playlists,” says Alperin, whose preferences ran from classical music to jazz. One DJ, he says, “would play whatever struck his fancy. One time he did a four-song set: My Sharona by The Knack, followed by Weird Al Yankovic’s parody, My Bologna, then the Chipmunks’ version, and then the original played at 45 rpm instead of 33.”

An Atlanta native, Alperin served as WRUR’s business manager his junior and senior years and learned the engineering side as well. After graduation, he worked at WHEC-TV in Rochester for nine years before embarking on a 27-year career in technical operations and engineering project management at CNN and Turner Broadcasting.

Lenny Bart ’80 was another student who turned his WRUR experience into a career in media. He has been in the television entertainment business for 35 years and currently serves as a vice president for WGN America. He selected a range of music for his shows, from “rock shows centered on blues-based music—Rolling Stones, Doors, Eric Clapton,” to new music.

“There really was no format at WRUR,” Bart says. “That was a dirty word.”

WRUR’s “Doing Our Thing” jingle was a mainstay of the station’s broadcast day.

As WRUR entered the 1990s, it was still in a golden age.

In April 1991, the campus welcomed the Violent Femmes to the Palestra, and WRUR’s Allison Scola ’94 was there to interview the band members. It was a typical kind of scoop, one that station DJs had been winning for years. Many groups like the Violent Femmes owed their success to college radio; it wasn’t hard to convince them that an interview with a student DJ on a low-wattage college station was worth their time.

When two popular alternative bands, the Throwing Muses and the Violent Femmes, came to the River Campus to perform at the Palestra in April 1991, WRUR’s Allison Scola ’94 had the chance to chat one-on-one with band members from the Violent Femmes.

More than 25 years later, Scola hasn’t forgotten. “I loved doing that interview,” she says. “I was a big fan of the Violent Femmes for years, so it was a thrill to meet them and talk with them about their music and career.”

Hear lead singer and guitarist Gordon Gano offer Scola some surprising details—such as his taste for chamber music—with the sounds of racquetball in the Palestra echoing in the background.

The segment also includes background on both bands from Scola, and a short clip from an interview with the Throwing Muses by British record label 4AD.

The Campus Times continued to feature prominently WRUR’s top albums, as it had for years. Campus news programs and election coverage—like interviews conducted in 1990 with candidates for governor, state assembly, and senator—were still a mainstay.

But technical problems, the likes the station hadn’t seen for about two decades, arose again. At the very same time, college radio was facing a challenging environment.

As enterprises that promised listeners what they couldn’t find anywhere else, college radio stations faced competition from digital audio, in the form of MP3 files distributed by peer-to-peer file-sharing services. By the early 2000s, the internet was offering what was once promised almost exclusively by college radio.

In the fall of 1993, Alex Cohen ’94 and Al Becker ’94 brought Yellowjackets football to Rochester from Francis Field at Washington University, just outside St. Louis.

In this third game of the season, the players faced challenging conditions. An exceptionally rainy period produced what Cohen called “a mini-Lake Ontario” around the 40-yard line. Becker noted that the conditions would make it difficult for quarterback Gregg Eisenberg ’94 to pass, putting added pressure on the Yellowjackets’ star tailbacks, Isaac Collins ’94 (nicknamed “Speed Gear” and a 2012 inductee in the University’s Athletic Hall of Fame) and Jeremy Hurd ’94 (named a First-Team Academic All-American at the end of the season).

The broadcast begins with nine minutes of analysis, followed by the game, with play-by-play commentary, starting at the 9:00 mark and running until the end of the first quarter.

Although the quarter ended with Wash U. ahead 3-0, the Yellowjackets rallied and finished on top, 14-6.

Ever since the dust-up with the chemistry department over station interference with faculty and student experiments in 1970, WRUR had wanted to find a way to return to a higher wattage. In 1993, the station thought it had finally found the means to do so. A new transmitter atop the Hyatt Hotel in downtown Rochester enabled WRUR to raise its power threefold. But the transmitter turned out to be too close to that of another station, WRMM, and the two stations together wound up interfering with Monroe County’s 911 system. The result was game-changing for WRUR. The station went off the air for much of the 1993–94 academic year, before the problem could be resolved. Student involvement with the station declined sharply.

It didn’t recover in the next year. Diminished personnel meant hours of dead air that ran afoul of Federal Communications Commission regulations. And the FCC was strengthening enforcement around the same time.

A partnership with WXXI Public Broadcasting helped place WRUR back on a firm footing.

WXXI had long sought to join forces with WRUR. As early as the summer of 1979, it proposed taking ownership of the license for WRUR-FM. The response from the WRUR Executive Board, as reported by the Campus Times, was characteristically unvarnished. The transfer of the license would "make the University appear in broadcasting circles and in the community at large as a foolish pawn, tricked by smooth talking."

WXXI made repeated overtures to the University regarding WRUR's license, all of which were rebuffed by students. In one case, according to the Campus Times, station manager Ted Vaczy ’88 ’95S (MBA) and program director Lenny Bart '80 accused WXXI of attempting a "coup."

But 24 years made quite a difference. When WRUR entered into the partnership in 2003, "reaction among the WRUR staff was mixed," says then-station manager Jared Lapin '05. "But among those closest to the operation, there was an understanding that the station needed additional resources and professional support.”

WXXI’s interest in WRUR was simple: there were no available FM frequencies in the Rochester area. “We had searched over the years in the hopes of starting a second FM station for our news programming,” says Susan Rogers, executive vice president of WXXI. “WRUR doesn’t just serve the campus. It can reach a potential audience of 800,000.”

Rogers notes that WRUR risked losing broadcast rights to a third-party station. Dead air “could open the door for religious broadcasters and other special interests to appeal to the FCC for a channel-share arrangement,” she says.

C. Mike Lindsey ’08 (T5), who became general manager of WRUR in 2006, says that on balance, the partnership was a good move.

“The University was faced with the decision to either sell the signal or partner with professionals who could help keep the station running,” he says. “U of R chose to partner with WXXI on the condition that they would help educate students on professional broadcasting skills."

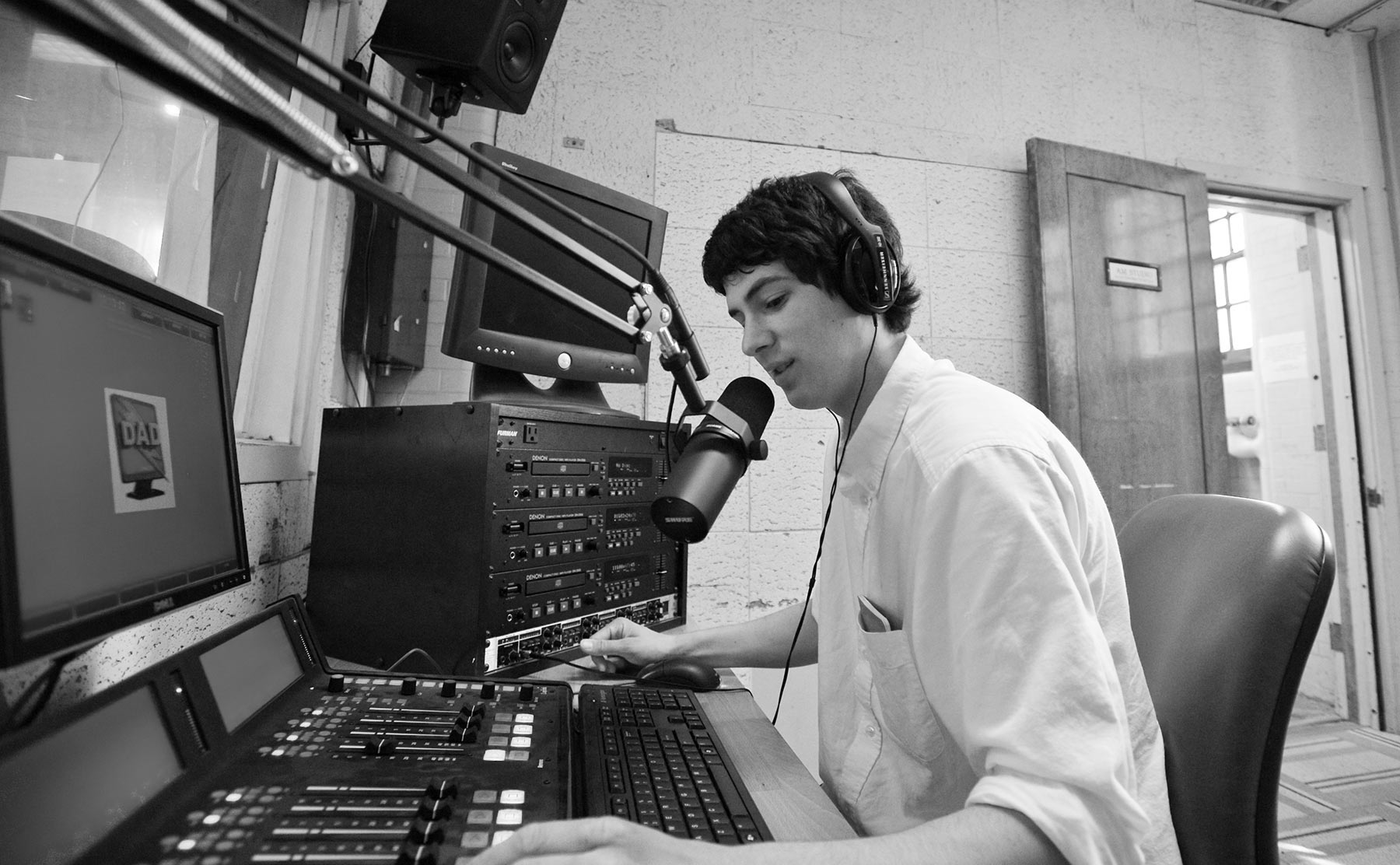

OVER THE AIR: C. Mike Lindsey ’08 (T5) was WRUR general manager in 2006, and helped work on a new partnership between the station and Rochester’s public radio affiliate WXXI. (University of Rochester photo / Richard Baker)

The agreement allowed WXXI to carry its morning news show on WRUR during the summer and to broadcast its late afternoon news program, "All Things Considered," on WRUR as well. In return for getting valuable airtime for its news programming, WXXI agreed to provide the students training. WXXI personnel taught a course on campus originally called Broadcasting in the Digital Age, since changed to Media in the Digital Age to reflect the evolving interests of students.

As college radio weathered its toughest decade, WRUR came out in relatively good shape. In the early 2010s, universities around the country, including Vanderbilt, Rice, and the University of San Francisco, were selling their student-run stations’ licenses.

“To be sure, hundreds of student-run stations of varying levels of quality and professionalism continue to broadcast within the Federal Communications Commission's historically designated noncommercial portion of the spectrum, 88.1 to 91.9 MHz,” reported the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2011 in an article “What’s Eating College Radio?” “But in a trend that industry observers say began in the 1990s, many others have been driven onto the Web or into oblivion when college administrators have decided to sell their licenses for much-needed cash.”

On Monday evenings, Abi Milner ’19—co-general manager of WRUR—and Molly Robins ’20—chief engineer—banter between the alt-rock songs they’ve selected for their two-hour evening program on WRUR-FM, “Breadtime.”

On Friday afternoons, Christophe Simpson ’19, a molecular genetics major, unwinds from the week on WRUR’s online station, The Sting, by sharing his thoughts on the premed experience at Rochester— interspersed with some of his favorite tunes.

Outside the door to the station’s Todd Union studio, Celia Konowe ’21, whose father, Adam Konowe ’90, was involved at the station all four years at Rochester, poses for a picture, holding a sign that sums up that attitude at WRUR today:

“New generation, same commitment.”

A WRUR WELCOME: The door to the station’s Todd Union studio is covered in 2008—as it is today—with stickers and signs. (University of Rochester photo / Brandon Vick)

In the fall of 2009, WRUR became part of a trend in college radio by launching an online station.

“In simplest terms, it’s WRUR’s internet-only counterpart to its terrestrial FM station,” says Nathan Snyder ’10. Snyder, who now heads the engineering department of a digital music distribution company, was the general station manager of WRUR when The Sting made its debut.

“The biggest thing we did was name it,” he says, half in jest. Truthfully, Snyder also oversaw the construction of two new internet-only recording studios, designed the logo, and helped create The Sting’s website.

HEAR THE STING: Nathan Snyder ’10 broadcasts from The Sting in 2009. Snyder was a driving force behind the new Internet-only station, a trend in college radio at the time and an outlet for student creativity and professional development. (University of Rochester photo / Brandon Vick)

The push for an internet-only radio station was multi-faceted and came in equal measures from the administration and WRUR’s student board. The University administration saw The Sting as a tool for career readiness; it was fertile ground for aspiring professional DJs to hone their craft—something that had once been the function of the AM station.

The students at WRUR saw The Sting as a natural expansion for their organization. Most important, internet radio, free from FCC oversight, became a canvas for creativity in a way that FM radio could no longer be.

“The Sting was a restriction-free space for edgier shows that didn’t fit the WRUR format,” Snyder says.

Anne-Marie Algier ’16W (EdD),

Associate dean of students and advisor for WRUR for over a decade

There’s a lot of value for the students. First, there are the people most of us think about—the DJs. But there are also a lot of other students involved that people don’t necessarily know, such as our engineering students. They learn the behind-the-scenes—what happens with all the infrastructure and all the different computers and equipment that make the station fuction. There’s a community of people that comes together from all different majors, and yet they come together over the radio station. It’s really kind of powerful.

There are some students who will only be involved with The Sting. The Sting doesn’t have the same FCC regulations, so [the students] can play whatever format they want. We allow much more variety in music on The Sting, whereas on the FM station, we have a triple-A [adult-album-alternative] format, so the show needs to follow those guidelines. That’s for the people who are more serious about learning radio—how do you get market share, how does your show actually build from one show to another, things like that. It’s a different kind of learning.

I hope it’s bright. I keep seeing more and more students involved with a crossover of majors. The Office of Alumni Relations has put together an advisory board of people who were involved in the station over the years. AnnMarie Cucci ’18W (EdD), assistant director there, and Adam Konowe ’90 have been the ones leading that effort. The alumni who are part of that board are very interested in helping the students be all they can be. It’s a very energizing time for the station.

For the aspiring FM DJ, as one might suspect, you can’t just show up to the WRUR station in Todd Union with a couple of CDs and expect to be on FM radio within the hour. There’s a process, not least of which entails racking up four hours of show time on The Sting.

“I had a show from 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. once,” says Milner. “But I did that to get on FM.”

If you’re new to WRUR, the first item on your to-do list is to schedule a training meeting with The Sting director. They’ll show you around the soundboard and guide you through the various nobs, lights, and sliders. Next is to sit in and observe a fellow DJ’s live Sting show. Once you get the idea, you schedule a pre-recording session with The Sting director to record a 30-minute sample of your show. If you’re angling for an FM slot, it must, of course, must be an FCC-appropriate genre. The director will then listen to your sample and either approve it to run as a full 60-minute segment on The Sting or explain why it didn’t measure up.

The most common reasons for a rejected show are choppy transitions, poor audio quality—a song downloaded from YouTube won’t cut it—or a violation of FCC rules.

The golden rule, for both FM radio and The Sting, is absolutely no swearing. “We enforce that rule as much as we can,” Milner laughs.

Once your sample is approved, the next step is to accumulate four hours of run time on The Sting, which generally breaks down to one hour a week, or one month of run time. If all goes smoothly, your sample is sent on to WXXI to review and approve for FM. There’s one final session with The Sting director to be retrained for FM broadcasting. Assuming everything goes well, you can have a show on FM in little more than two months.

So, if a DJ can script and pre-record a show and then play it later, how is internet radio different from a podcast?

“One of the things that The Sting directors try to impress upon new DJs,” says co-general manager Nate Nickerson ’20, “is that a podcast is exactly what we’re not.”

Pre-recording is actively discouraged and is only done with ample advance notice if the DJ can’t make their show’s regular time slot. Of the two studios devoted to The Sting, the pre-record studio is much smaller than its live-radio counterpart. It’s sparsely decorated, a bit dusty, and looks, frankly, a bit crummy.

IN THE STUDIO: The current WRUR co-general managers Nate Nickerson ’20, left, and Abi Milner s19 recording in the smaller of The Sting’s two studios. The Sting is the digital counterpart to WRUR’s over-the-air broadcast station. (University of Rochester photo / Brandon Vick)

“We want [the pre-record studio] to be as unwelcoming as possible,” Nickerson jokes. Live radio helps to preserve the organic nature of a radio show, he explains, and an authentic, live stream of consciousness is valuable.

“The accidents are very important,” agrees Milner. “It’s what makes radio, radio.”

In the age of instant streaming services—music, podcasts, video—WRUR lives on. What’s its role in this new environment?

For one thing, it may not matter which technology delivers the programming.

“I think college radio is something special and it doesn’t necessarily have to turn into anything new,” says Milner. “I want us to keep the college radio culture as this very raw and angsty ‘we’re tired, we’re all studying, but we’re still sharing music that we love’ and sharing it with the campus community.”

Carrie Taschman ’18, co-general manager during her senior year, puts it succinctly: “Well, the nice thing about radio is that it can be what you want.”

CAN’T STOP THE SIGNAL: Recent University of Rochester graduates Carrie Taschman ’18 and Toby Kashket ’18 spent their senior year as WRUR station managers.

The internet’s fleet-footed ability to adapt to the latest technologies and ideas ensures its longevity. Perhaps the opposite is true of college radio. It is steadfast, not despite outmoded traditions, but because of them. Like college radio in its early decades, The Sting does not have a large audience as of yet. But for the students who take part in its operation, the size of the audience isn’t what gives value to college radio. It’s the student behind the mic.

It's also the unique potential of college radio to capture a community. Last spring, as she prepared to graduate, WRUR’s other general manager, Toby Kashket ’18, said that The Sting isn’t just an outlet for music. The station “is a great way for people to come in and do a talk show. We have lots of different talk shows dealing with many different issues, like queer issues, and we have a feminist sports show.”

She adds that the station’s future plans include “getting involved in ways that benefit other clubs,” including live-streaming of events.

“I would hope that The Sting would become a part of the university brand that students can identify with,” says Snyder, “the same way that you would identify with a sports team.” There’s something to be gained from listening to The Sting, he says. A connection with the campus community.

Were you a part of WRUR history? As a manager, engineer, disc jockey, or audience member? Share your story below and we’ll post your memories here. Thank you for sharing.

Additional reporting by: Peter Iglinski, Jim Mandelaro, Susan Ziegler ’19.

Archival research: Melissa Mead. Audio engineering: Joe Hagen ’20.

Videography and graphics: Dawn Wendt. Web design: David Hunt, Lori Packer.