Features

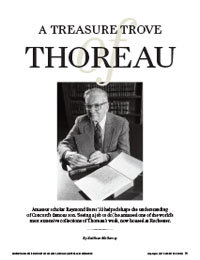

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)When Henry David Thoreau was born, 200 years ago this July 12, he arrived in the wake of a calamity.

In 1816, known around the world as the “year with no summer,” ash, dust, and sulfur dioxide choked the atmosphere, spewed there by the 1815 eruption of Indonesia’s volcanic Mount Tambora.

Crops failed in New England as frost conditions persisted through that summer. Farm families, including the Thoreaus soon after Henry’s birth, were driven from their land.

Thoreau’s father, John, tried to make a living as a storekeeper a few miles away. Ultimately, the family found its way back to Concord, Massachusetts, with a pencil-making business that transformed American pencil manufacturing. They never returned to the land as farmers.

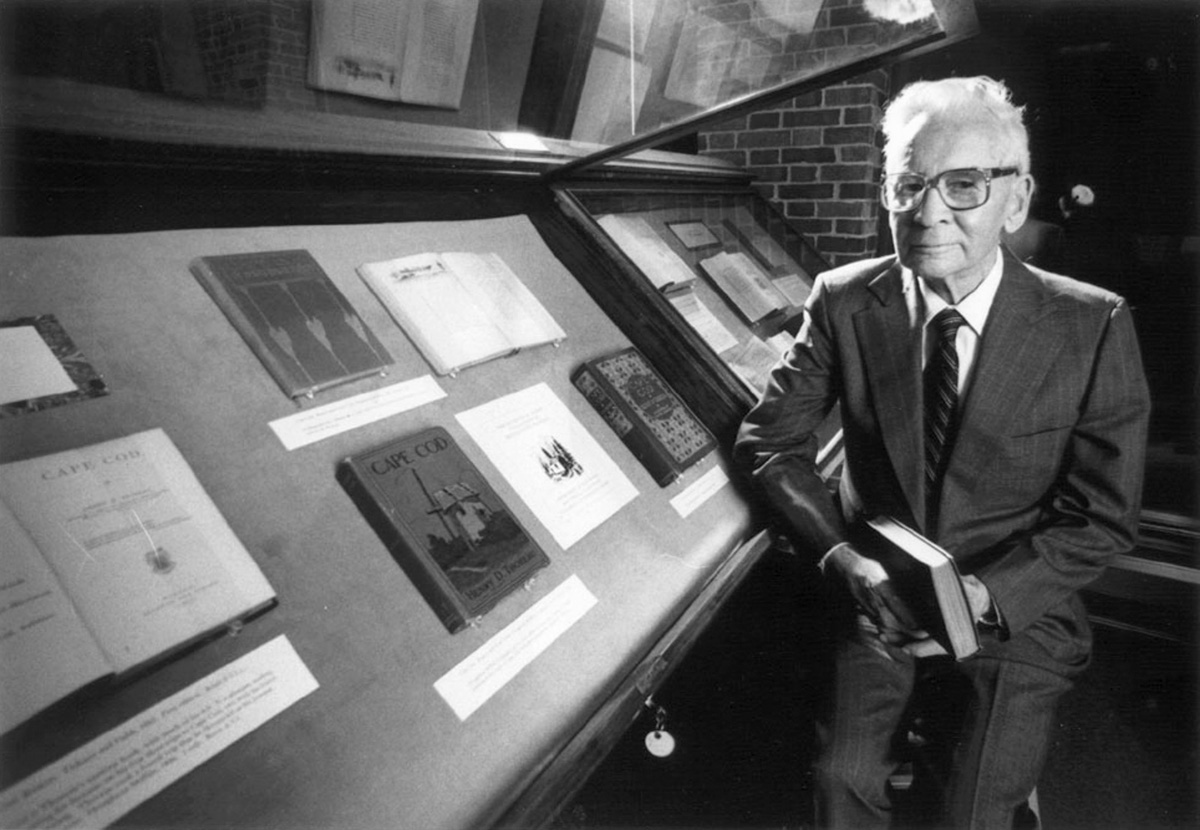

EARTHY INTERESTS: Henry David Thoreau, born 200 years ago this July, may be most closely associated now with ideas of wilderness,

but he was deeply absorbed in the agricultural practices of his community, too. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

EARTHY INTERESTS: Henry David Thoreau, born 200 years ago this July, may be most closely associated now with ideas of wilderness,

but he was deeply absorbed in the agricultural practices of his community, too. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)But there is no American writer more closely identified with the natural world than Thoreau. Although only two of his books—A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) and Walden: or, Life in the Woods (1854)—were published in his lifetime, his work grew steadily in popularity after his death from tuberculosis in 1862.

His words in Walden are familiar even to people who have never opened its cover:

“Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!”

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Among the many who have thrilled to his words was the late Raymond Borst ’33.

He came by his enthusiasm incidentally. On a business trip to Chicago in the 1940s, he picked up a copy of Walden at a hotel bookshop. His wife, Anne, wanted it for her book club. Traveling home by train to Auburn, New York, Borst began to read Thoreau’s account of living a simple life near Walden Pond.

That train trip was the start of a lifelong project. Beginning modestly, the Borsts took to rare-book hunting as a pleasant way to make day trips. They contacted book dealers to say they were interested in knowing when the dealers received an unusual edition. And as time passed, Borst amassed one of the world’s most extensive Thoreau collections, which grew so large that the couple added a wing to their house to contain it.

In 1996, five years before his death at age 91, Borst donated his collection of roughly 800 items to the University, prompted in part by his long friendship with the then head of the library’s rare books department, Peter Dzwonkoski. There is a strong connection between collectors and curators, says Jessica Lacher-Feldman, the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation. “Our work in special collections is as much about relationships as it is with preserving and making accessible rare and unique materials.”

Featuring first editions of all of Thoreau’s published books, plus a wide range of rare 19th-century magazines and pamphlets containing articles unavailable in any other form, the Raymond R. Borst Collection of Henry David Thoreau became the University’s best printed collection in American literature. It complements the libraries’ other 19th-century American holdings, such as collections for Frederick Douglass, abolitionists Isaac and Amy Post, and Secretary of State William Henry Seward.

In a fundamental way, Borst—sunny, friendly, and devoted to his family—and the famously odd, seemingly solitary Thoreau make an unlikely pair. But they shared a love of nature and a deep- rooted interest in the agricultural world. After Borst graduated from Rochester, he went to work for the Civilian Conservation Corps. But before long, his father asked him to return with his brother to their hometown of Auburn to take over the family’s farm-equipment business. There, Borst bought a house built in 1813 with no plumbing and little electrical wiring—a place where the Thoreau of Walden might have felt at home. He did some farming on its 160 acres and interacted daily with farmers at his business. In Thoreau, he had found a writer who had occupied a similar world.

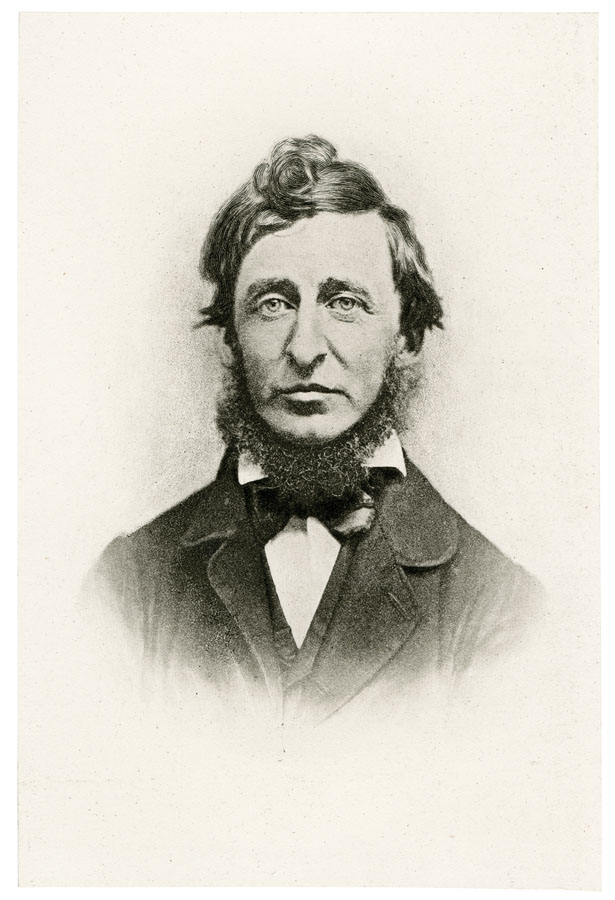

DOCUMENTED LIFE: Raymond Borst ’33 compiled The Thoreau Log: A Documentary Life of Henry David Thoreau, 1817–1862 (G. K. Hall, 1992), an exacting work that pulls together journal entries, correspondence, newspaper articles, and even library records to give account of Thoreau’s life, day by day. Here, the edited typescript appears alongside the first edition of the published work. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

DOCUMENTED LIFE: Raymond Borst ’33 compiled The Thoreau Log: A Documentary Life of Henry David Thoreau, 1817–1862 (G. K. Hall, 1992), an exacting work that pulls together journal entries, correspondence, newspaper articles, and even library records to give account of Thoreau’s life, day by day. Here, the edited typescript appears alongside the first edition of the published work. (Photo: Adam Fenster)For scholars, there have been many Thoreaus: the political Thoreau of “Civil Disobedience,” important for issues of social justice and individual rights of protest; the ecological Thoreau, one of the first great advocates of an environmental understanding of nature, the world, and the human place in it; the scientific Thoreau, whose work contributed to the formulation of scientific methodologies and intersecting natural systems of the type described by 19th-century scientists Louis Agassiz and Alexander von Humboldt.

And increasingly, an agrarian Thoreau has emerged—one who was not just invested in wilderness, but also appreciated the human manipulation of nature and its use for human productivity. He was acutely knowledgeable about the practices of local farmers in eastern Massachusetts.

Laura Dassow Walls, the William P. and Hazel B. White Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, is the author of Henry David Thoreau: A Life (University of Chicago Press, 2017). Released in conjunction with the bicentennial of Thoreau’s birth, the book is the first full-scale biography to be published in almost 30 years. Walls’s research makes clear that Thoreau was in constant conversation with farmers. He wasn’t a member of the Concord Farmers’ Club, but its membership lists correspond to his circle of friends, and his name comes up regularly in the records of the club’s meetings. “They’re talking to him, and he’s talking to them,” she says.

“In a lot of ways, the agrarian aspect of his work and thinking is at the core of all those other understandings of Thoreau—social justice, environmental justice, scientific, ecological,” says Walls. He wants to know why farms are failing. Friends are losing their land, and he approaches the question as a matter of social justice. He investigates how farmers could better grow their crops, and that’s a question of harnessing science. He tries to understand how land could reach a condition where nothing would grow, and that’s a question of environmental justice.

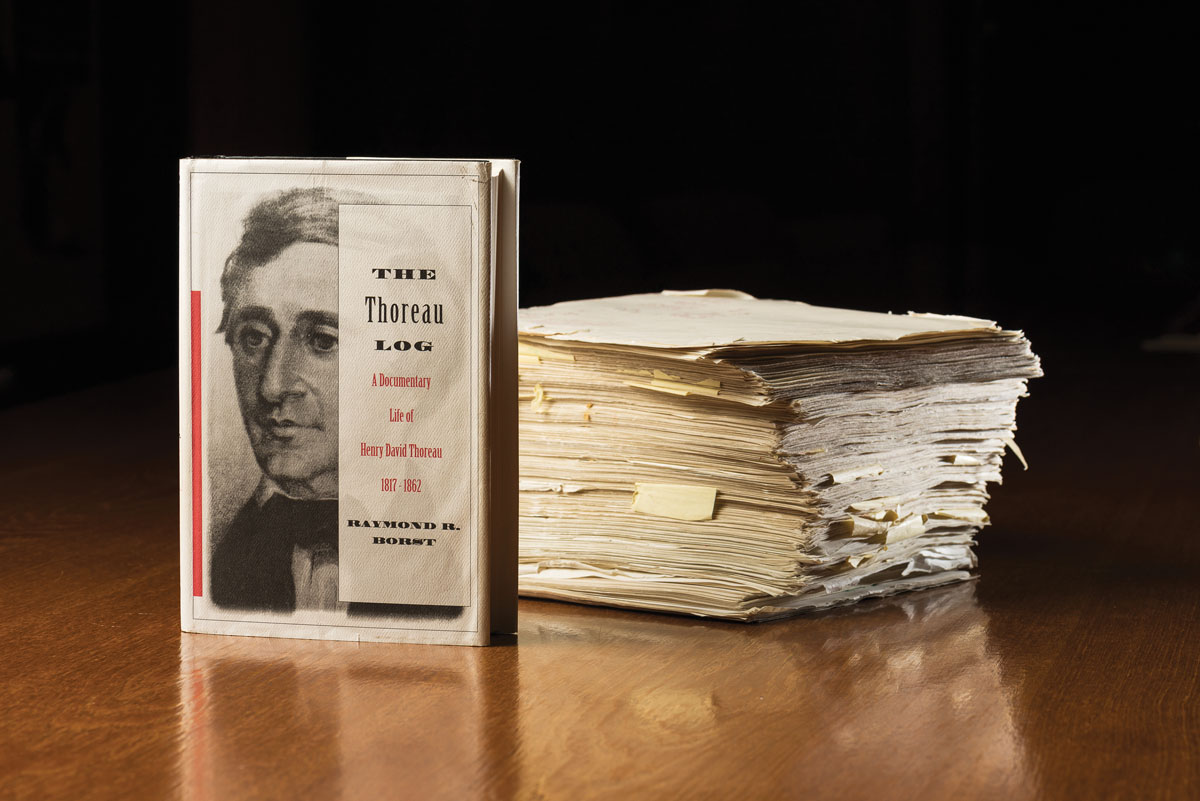

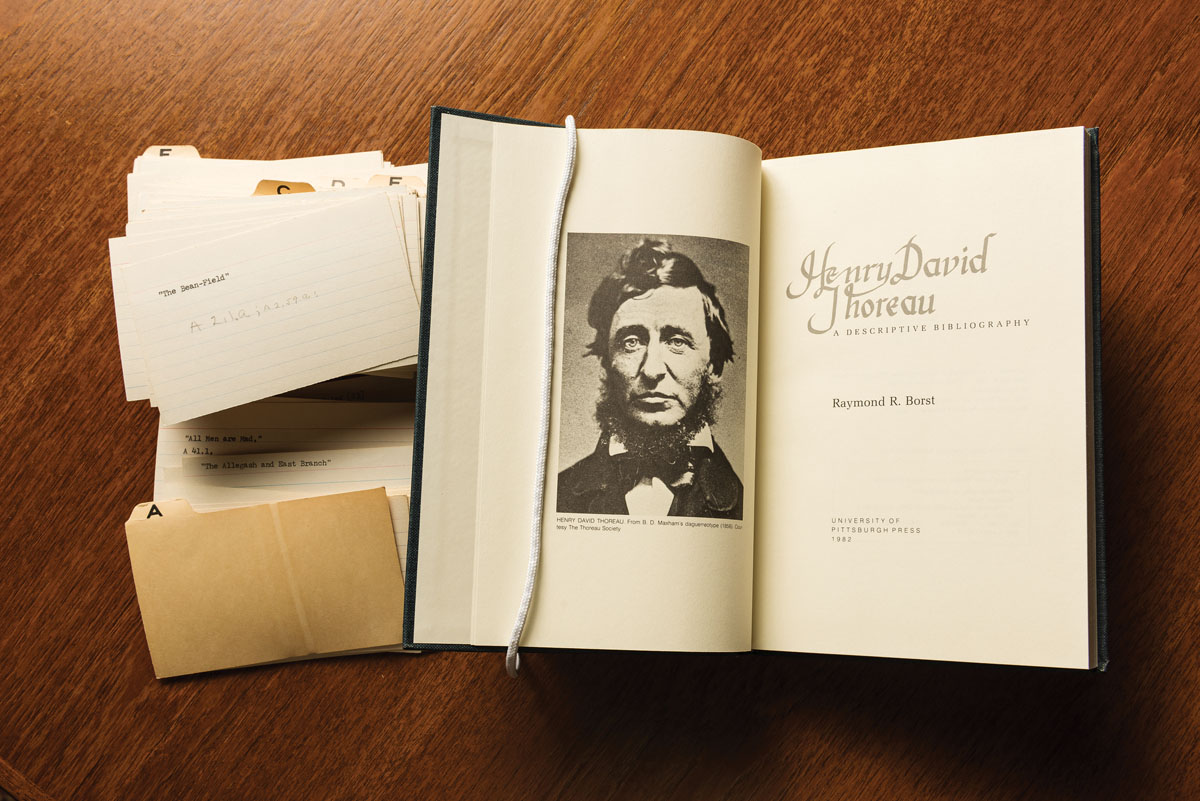

RECORD BOOK: Borst’s first foray into scholarly work was Henry David Thoreau: A Descriptive Bibliography (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982). Borst traveled to libraries in Europe and around the United States to produce this detailed catalog of all of Thoreau’s publications, a resource still relied on by scholars and book dealers. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

RECORD BOOK: Borst’s first foray into scholarly work was Henry David Thoreau: A Descriptive Bibliography (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982). Borst traveled to libraries in Europe and around the United States to produce this detailed catalog of all of Thoreau’s publications, a resource still relied on by scholars and book dealers. (Photo: Adam Fenster)New England farmers were mortgaging their farms to afford technologies they hoped would help them prosper as the railroad forced them to compete with farmers working more fertile lands to the west, in places like New York and Ohio. When they couldn’t make their payments, they lost their farms. “This, to him, is tragic,” says Walls. “And a lot of this comes home to him because these are his neighbors.”

Although people don’t typically think of Thoreau as a man of his community, Borst was well known for his ability to connect with others. He cocreated a local fire department, directed the Auburn Chamber of Commerce, and was president of both a regional art and history museum and an art center.

Whatever he did, he ended up being chosen to lead the group, says his daughter Cynthia Sherwood ’83 (MA). “He just thoroughly enjoyed people,” she says.

In 1977, Anne Borst died, and the always busy Ray found himself at a loss. And just at that time, the University of Pittsburgh asked him to create a descriptive bibliography for Thoreau.

The work became an exhaustive catalog of Thoreau’s publications as physical objects, noting the paper on which they were printed, their ink and binding, and the circumstances of their publication. With his daughter, Borst traveled to libraries in Europe and at Harvard and to small institutions with Thoreau holdings. He did much of his writing at his cabin in the Adirondacks.

WORLDWIDE WALDEN: Walden: or, Life in the Woods is Thoreau’s best-known work, popular with readers around the world. Editions in the Borst collection include volumes published in (clockwise from top left) Sweden, Denmark, Israel, Brazil, Italy, France, and Switzerland. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

WORLDWIDE WALDEN: Walden: or, Life in the Woods is Thoreau’s best-known work, popular with readers around the world. Editions in the Borst collection include volumes published in (clockwise from top left) Sweden, Denmark, Israel, Brazil, Italy, France, and Switzerland. (Photo: Adam Fenster)“He needed a project, and this just dropped from the sky right into his lap,” says Sherwood. The University of Pittsburgh Press published Henry David Thoreau: A Descriptive Bibliography in 1982. Almost all rare-book dealers refer to Borst’s work when identifying a volume for sale. Andrea Reithmayr, Rochester’s special collections librarian for rare books and conservation, calls it an “incredible legacy.”

A decade later, Borst published The Thoreau Log: A Documentary Life of Henry David Thoreau, 1817–1862 (G. K. Hall, 1992), a description—culled from Thoreau’s own Journal, newspaper articles, library lending records, correspondence, and other materials—of Thoreau’s activities for as many days of his life as could be accounted for. The Log represents the very rare instance of an amateur’s work becoming a touchstone for scholars. Walls says she began her biography of Thoreau by working with the Log. “It’s a treasure trove for researchers, no matter what you’re interested in,” she says.

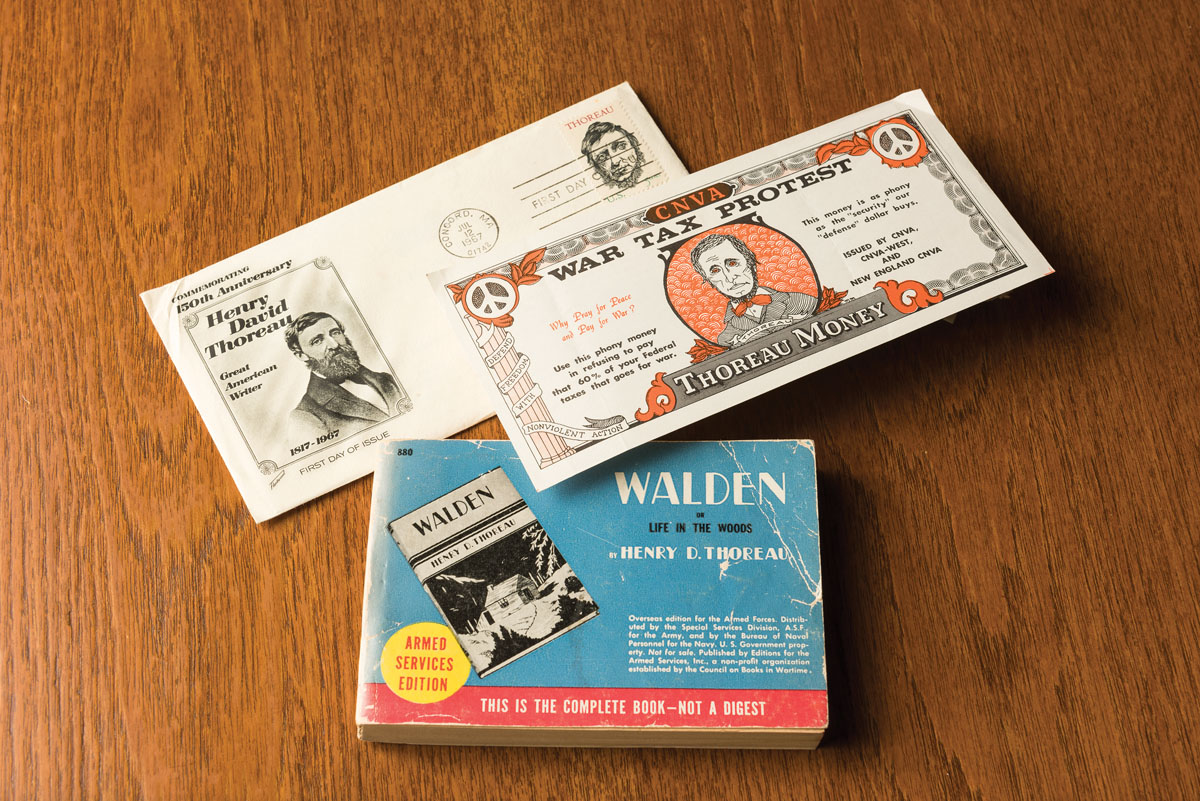

POP-CULTURE THOREAU: Borst’s collection includes (from top) a United States postage stamp and envelope commemorating the sesquicentennial of Thoreau’s birth, hand-canceled on July 12, 1967, in Concord; an example of “Thoreau Money,” produced by the Committee for Nonviolent Action in the 1960s and distributed during antiwar protests; and an edition of Walden created for the Armed Services during World War II. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

POP-CULTURE THOREAU: Borst’s collection includes (from top) a United States postage stamp and envelope commemorating the sesquicentennial of Thoreau’s birth, hand-canceled on July 12, 1967, in Concord; an example of “Thoreau Money,” produced by the Committee for Nonviolent Action in the 1960s and distributed during antiwar protests; and an edition of Walden created for the Armed Services during World War II. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Different from critical scholarship, the Log is a compilation of coincidences and events in Thoreau’s life, curated from a vast array of sources and set in chronological order. In it, Borst creates a tactile and local Thoreau, allowing readers to follow, in minute detail, the activities of his daily life—the people he talked to, the places he went on his walks, the commentary he had on local agricultural practices.

Thoreau’s writing has been studied and commented on by people as varied as Mahatma Gandhi and Hannah Arendt. But Borst gives readers Thoreau in Concord, with his feet on the ground. He tells them not just when Thoreau and his brother built the boat they rowed down the Concord and Merrimack (in the spring of 1839), but what they named it (the “Musketaquid”), how they celebrated the upcoming journey (with a “melon spree” party), and to whom Thoreau later sold the boat (novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne).

Naturalist Louis Agassiz once wrote to Thoreau, asking him to collect specimens for his museum. Thoreau did. Borst gave himself a similar task—with the same dedication and focus that he brought to creating his collection of Thoreau’s works, he gathered little bits of information and created in the Log a museum of Thoreau’s life.

“He was the kind of person that, if he saw a job to do, he did it,” says Sherwood.

At Walden’s conclusion, Thoreau writes of taking a hammer in hand: “Drive a nail home and clinch it so faithfully that you can wake up in the night and think of your work with satisfaction . . . Every nail driven should be as another rivet in the machine of the universe, you are carrying on the work.”

Borst listened, and so he did.