The Grand Dame of Sex Education

The Grand Dame of Sex Education

Historian Ellen Singer More ’79 (PhD) explores the complex legacy of pioneering sex educator Mary Calderone ’39M (MD)

UNIVERSALIST: “We are all sexual, all of our lives, each in our own unique way at any given moment,” said Calderone, a Quaker, who believed sexuality was a divinely bestowed gift to be celebrated. While she shocked some, she alienated others, particularly the young, beginning in the late 1960s, with her espousal of what she called “responsible sexuality.”

From the 1960s until well into the 1980s, Mary Calderone ’39M (MD) was a high-profile and a divisive figure in American culture.

That may have been inevitable, given the subject of her work and the social context in which she operated.

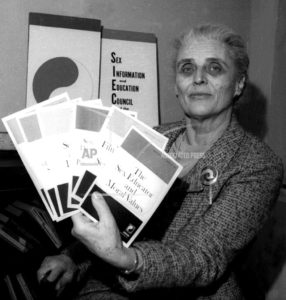

Calderone was the first medical director of the Planned Parenthood Federation, holding that position during the approval and roll-out of the first oral contraceptive in the United States. In 1964, she left the federation to cofound the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States, or SIECUS (since 2019 known as SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change). She was the author or coauthor of multiple books, including The Manual of Contraceptive Practices (1964), The Family Book about Sexuality (1980), and Talking with Your Child about Sex (1984).

The mission of SIECUS under Calderone’s leadership was not only to convey accurate information about sex, but also to change attitudes. At a time when parents, educators, and religious and civic leaders expressed great anxiety over the implications of “the pill” for the sexual lives of young people, Calderone and her colleagues advanced a positive view of sexuality as a natural and healthy part of life that emerges during childhood and can remain vibrant throughout life.

At the start of her career, in the 1940s, many of her contemporaries found her views shocking. By the late 1960s, however, she began to lose her radical edge. In The Transformation of American Sex Education: Mary Calderone and the Fight for Sexual Health (New York University Press, 2022), Ellen More ’79 (PhD) traces Calderone’s career and explores her profound and complicated legacy in the context of the larger history of sex education in the United States.

More was a postdoc at the Medical Center in 1984 when she first met Calderone. A historian by training—of Tudor-Stuart England, to be exact—More, much like Calderone, shaped her career in the context of her family circumstances. Now a medical historian and professor emeritus in psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, More had a husband with a job at Kodak and a young daughter when she was starting her career. She was nearing the completion of her dissertation, taking stock of the opportunities available to her locally, when she was offered the chance to develop and teach Rochester’s first undergraduate course on the history of the American medical profession. Questions raised by her students—many of them young women preparing for careers in medicine—and a tip from then professor of medicine Edward Atwater ’50 about a rich collection of materials related to early women physicians he had amassed and donated to the Miner Library (now part of the Edward C. Atwater Collection of American Popular Medicine and Health Reform) led her to research women physicians, and eventually, Calderone.

“Calderone herself was not someone you would get close and personal with,” More says, recalling that first meeting and several more with Calderone later in the 1980s. But she was deeply charismatic. The daughter of one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century, Edward Steichen, Calderone, who was born in 1904, spent her childhood jet-setting between Paris and New York and finished off her secondary education at New York’s elite Brearley School.

Calderone always expected to be interviewed wherever she went, and she had been interviewed countless times . . . in the back of my mind I knew that I wanted to write about her. —Ellen Singer More

One of the challenges of telling Calderone’s story is contending with how much public discourse on sexuality has changed in the years since she was active, and since her death in 1998. It’s tempting to ask, what would Calderone have said?

We’ll never know. But Calderone was motivated throughout her life by “a deeply held belief in universalism,” More says. A Quaker throughout her life, “she was interested in universalizing. That was her orientation. She wanted to express that sexuality was a universal human need and a universal, underlying biological system.

“However it expressed itself, it was part of every human.”

Who Was Mary Calderone ’39M (MD)? A Brief Introduction in Five Scenes

The New York Times anointed Mary Calderone ’39M (MD) “the grand dame of sex education” when she died in 1998.

But she, like all great social pioneers, was a complicated, nuanced figure who devoted her considerable energy on projects that were not met with wholehearted enthusiasm by the society she was hoping to help. Here are five important ideas about her life and work, drawn from The Transformation of American Sex Education: Mary Calderone and the Fight for Sexual Health (New York University Press, 2022), by Ellen More ’79 (PhD).

1. As a child, Calderone received mixed messages at home about sexuality.

Calderone was born as Mary Steichen in 1904 to parents steeped in the transatlantic artistic avant-garde. Her father was the renowned photographer Edward Steichen, credited along with Alfred Stieglitz as a major figure in the transformation of photography into an art form. During Mary’s childhood and adolescence, Steichen became a pioneer in fashion photography, producing, More writes, “wide-ranging studies of the human form,” imbued with “the modernist view of the body as a subject of straightforwardly sensuous representation.”

Mary’s mother, Clara, by contrast, was “a perfect exemplar of Victorian sexual attitudes,” More says, and “clearly very uncomfortable with her husband’s sexual openness.”

Following a common Victorian practice, Clara put Mary to bed in aluminum mittens designed to prevent masturbation. But despite Steichen’s seemingly libertine attitudes, according to More there is no evidence that Steichen ever objected to Clara’s treatment of Mary—treatment that Calderone later characterized as sexual shaming that left a deep impact on her. More relates another incident from Calderone’s childhood that made a lasting impression: a teenaged gardener exposed himself to Calderone while the two were in a shed. “I think any parent would be horrified,” More says. But what remained with Calderone years later were Steichen’s words to her, after he fired the gardener: “Now you have lost your innocence.”

“Those words were burned into her memory and were in some ways, some of the most important ones ever said to her,” More says. “I really believe that her campaign to destigmatize sexuality—and particularly children’s sexuality, their sense of pleasure in their own sexual beings—is rooted in these experiences of her childhood.”

2. Calderone’s medical school mentor was George Washington Corner, who later was the lead scientist in the identification of progesterone, key to the development of the contraceptive pill.

After briefly taking up theater, Calderone, who majored in chemistry at Vassar, decided to pursue medicine. She was 30 years old when she arrived at the School of Medicine and Dentistry for the doctoral program in the physiology of nutrition. But on her third day in the program, Calderone paid a visit to Dean George Whipple and successfully petitioned him to be transferred into the MD program—likely her intended destination all along, More suggests.

There she met Corner, a professor of anatomy and an endocrinologist. Corner, who was doing the research that led eventually to the isolation of the hormone progesterone, was also at work on two sex education books for children: Attaining Manhood: A Doctor Talks to Boys about Sex (1938) and Attaining Womanhood: A Doctor Talks to Girls about Sex (1939). Calderone was one of two students of Corner’s at Rochester who went on to distinction in the field of human sexuality; the other was William Masters ’43M (MD), the gynecologist who went on to write, with his research partner and wife, Virginia Johnson, Human Sexual Response (1966), popularly known as “Masters and Johnson.”

3. Calderone believed that changing attitudes about sex was a necessary precursor to improving sex education. At a time when sex education was typically confined to lessons on reproduction, she urged her medical colleagues, as well as parent and civic groups, to view sex as a positive end in itself. At Planned Parenthood, she urged greater social and cultural acceptance of birth control among physicians as well as religious establishments.

After graduating from the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Calderone earned a master’s degree in public health at Columbia, where she also met and married fellow physician and public health advocate, Frank Calderone. Then she began her medical career as a physician in the public schools of Great Neck, New York, where she frequently delivered workshops to PTA groups on how to talk to children about sex.

Calderone’s lectures “deviated from the typical [physician’s] script in significant ways,” More writes. As Calderone told parents in one lecture, “My job, I think, is to help you achieve good feelings about sex. If necessary—to change your feelings. Once you feel that sex is right, and warm, and a good part of life, you will have no difficulty letting your child in on this right and warm and good thing.”

Calderone took that view with her when she became the first medical director of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1953. In 1960, when the FDA approved the first oral contraceptive, Calderone lobbied the American Public Health Association and the American Medical Association to endorse contraception as part of standard medical practice.

As early as the late 1950s, and throughout the 1960s, Calderone promoted the wide availability of a range of birth control methods as an antidote to abortion. In 1958, Calderone organized a conference on abortion (practiced among physicians more widely than often realized) as a “social disease” that could be cured by greater social and cultural acceptance of—and therefore, use of—contraception. Although Calderone spoke about the need for women to control their reproduction, she did not frame abortion in the language of choice or of bodily autonomy—but rather as evidence of a failure of society.

4. Calderone framed sexuality as an integral part of personal identity. But she said or wrote very little on the subject of gender identity.

Calderone talked about sexuality as not only a positive force, but as an integral aspect of human identity. In a 1967 interview in Parade magazine, Calderone said, “Too many people think you complete sex education by teaching reproduction. Sex education has to be far more than that. Sex involves something you are, not just something you do.”

But, More explains, “Calderone was no theoretician, nor did she formulate a model of either gender-or sexual-identity formation.” To the extent that Calderone addressed gender identity, she “conformed loosely to a Freudian developmental template,” More argues, citing as evidence Calderone’s remarks to a parent group in the late 1940s: “Even the tiniest baby will begin to get an impression of man-ness and woman-ness. . . [As] a child grows up in the family he becomes aware of what a man is . . . [and] . . . what being a woman means.”

5. Starting in the late 1960s, Calderone came under attack by participants in a growing, grassroots conservative movement. But she was no libertine, as those critics claimed, and simultaneously faced another group of critics, on the cultural left.

More writes that by the mid-to-late 1960s, “Calderone seemed firmly established as the ‘mother of sex education’ in the United States.” But at that same time, an organized movement against sex education was emerging in Southern California, with Calderone and SIECUS as its target. Calderone was condemned for her remarks normalizing masturbation and homosexuality. After an appearance Calderone made in Milwaukee in 1971, a protester took the microphone and said, “Dr. Calderone, I accuse you of rape of the mind.”

Yet sexual mores were also “liberalizing much faster than SIECUS under Calderone’s leadership could or would acknowledge,” More writes. Calderone did not align herself with the feminist movement, nor would she aid in the destigmatization of premarital sex by weighing in on the moral debate surrounding it.

Instead, Calderone often exhorted individuals to develop their own moral frameworks. It was an approach that More suggests was likely rooted in Calderone’s Quakerism, but which many young people saw not as a principled position, but as a dodge.

— By Karen McCally ’02 (PhD)

This article originally appeared in the spring 2022 issue of the Rochester Review magazine.