When Martha Graham danced…

When Martha Graham danced…

A year-long teaching post at the Eastman School of Music provided Martha Graham with “a new adventure of seeking” that would prove pivotal to her place as a pioneering dancer and choreographer, according to a new biography.

Neil Baldwin ’69. PHOTO BY BLUE MOON PHOTOGRAPHY NJ

As a scholar and author, Neil Baldwin ’69 willingly expresses an affinity for the currents of American culture that lead to reinvention—older currents being reconfigured and recast in new ways.

If through lines can be found in his life’s work as poet, critic, and biographer, that might be one. The former founding executive director of the National Book Foundation and now a professor emeritus at Montclair State University, Baldwin has written highly regarded books about poet and physician William Carlos Williams, visual artist Man Ray, inventor Thomas Edison, and auto magnate Henry Ford, among others.

A new biography of modern American dance icon Martha Graham—the first in more than 30 years—seemed a logical addition to that pantheon.

“I felt like [Graham] had been left out of the narrative that I’ve been creating for my whole life about American art,” Baldwin says. “I thought, ‘Wait a second . . . what about dance? I did art. I did literature. I did technology.’”

“At a rather late point in my career, I suddenly am hit over the head with this physical nature of modernism, movement- wise, and how she used her body to create a new aesthetic,” he says. “Again, the key note is new, to make it new, as Ezra Pound says, to carve space and to create shapes with the body that no one’s ever done before—Graham was the pioneer of physicality.”

After more than a decade of research and dozens of interviews with Graham dancers— former and current—Baldwin published Martha Graham, When Dance Became Modern: A Life in 2022.

Listed in many year-end round-ups as one of the best books of the year, the biography recounts Graham’s creative life, from growing up in Pittsburgh to her status as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Among the many institutions where Graham left a lasting mark was the Eastman School of Music. From the fall of 1925 to the spring 1926, Graham participated in an innovative, but short-lived, program of “dance and dramatic action” at Eastman.

“She was hired with the express reassurance that she was going to do something different than just conventional ballet at Eastman. And she welcomed that,” Baldwin says. “In terms of the theme of the book, “When Dance Became Modern,” that’s really important because the roots of her modern mode can definitely be traced to that year.”

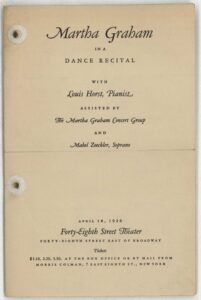

ENCORE: Graham and her Eastman students reprised the New York City debut for a late spring recital in Rochester. MARTHA GRAHAM COLLECTION/MUSIC DIVISION/LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

What brought Graham to Eastman?

At that point, she was starting to develop her own choreographic style of movement. And when she was hired by Rouben Mamoulian who was the head of a newly established school of dance and dramatic action under George Eastman, she was told that she could use the class to experiment in developing her individual technique, which is what she was really itching to do at that point.

She had paid her dues in vaudeville and as a showgirl. She had traveled back and forth across the country and performed in all these little towns from east to west and north to south with Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis and their dance company.

Did she have a plan in mind as she joined the faculty?

When she left the Greenwich Village Follies and moved beyond vaudeville, she said she wanted to create her own dances in her own body and that was crucial to the Eastman residency. Intrinsic to the origin of modern dance, is there was no formal, pre-existing repertory. There’s no, “Oh, let’s do Swan Lake.” Everybody has the pattern and the narrative and the staging of Swan Lake to follow, whereas Graham was concocting dances from simple, pedestrian movements like walking, running, skipping, and leaping and drawing upon her students’ inner energy to make new movement patterns come to life.

Is it fair to say the roots of the Martha Graham Dance Company can be traced to her time at Eastman?

Three Eastman students—Evelyn Sabin, Betty Macdonald, and Thelma Biracree—were the nucleus of what became her company. Looking back upon that nascent period, which was less than a year, she was teaching in New York City at John Murray Anderson’s school and then she would take the train up to Eastman and teach her classes and she went back and forth like that from New York to Rochester. She featured Eastman students in her New York City premiere in April 1926.

Did you work with Eastman as you were recounting Graham’s time in Rochester?

The Eastman School’s historian, Vince Lenti, and his books, for example, For the Enrichment of the Community: George Eastman and the Founding of the Eastman School of Music (Meliora Press, 2004), were very helpful. The head of special collections at the Sibley Music Library, David Peter Coppen, was also extremely helpful. Paul Horgan’s memoir of Mamoulian was a gem, as were some old Rochester Democrat and Chronicle clippings files I discovered in the Reading Room of the Library of Congress. I would say that the story of Graham’s time at Rochester is more known among the Eastman community than the larger University community.

How do you think your time as a student at Rochester set you on your path as a writer and scholar?

It was my freshman or sophomore year, when the Outside Speakers Committee brought the charismatic cultural critic Susan Sontag to campus. I don’t think she was even 30 years old. She had just published what would become her most enduring classic, Against Interpretation. I remember all of us students sitting on the floor in a circle around her. That was my first really vivid inspiration about how you could write about the alchemy of societal mores and art and performance and visual art. I still return to Against Interpretation every few years.

During my freshman year, I took a course called American Intellectual History with the brilliant, resonant-voiced, impassioned professor Loren Baritz in the history department. The startling keyword for me was “intellectual”—the core of his thesis in his book City on a Hill. That was a major cataclysmic epiphany for 18-year-old me.

— Written by Scott Hauser

This article originally appeared in the spring 2023 issue of Rochester Review magazine.