Campus Life

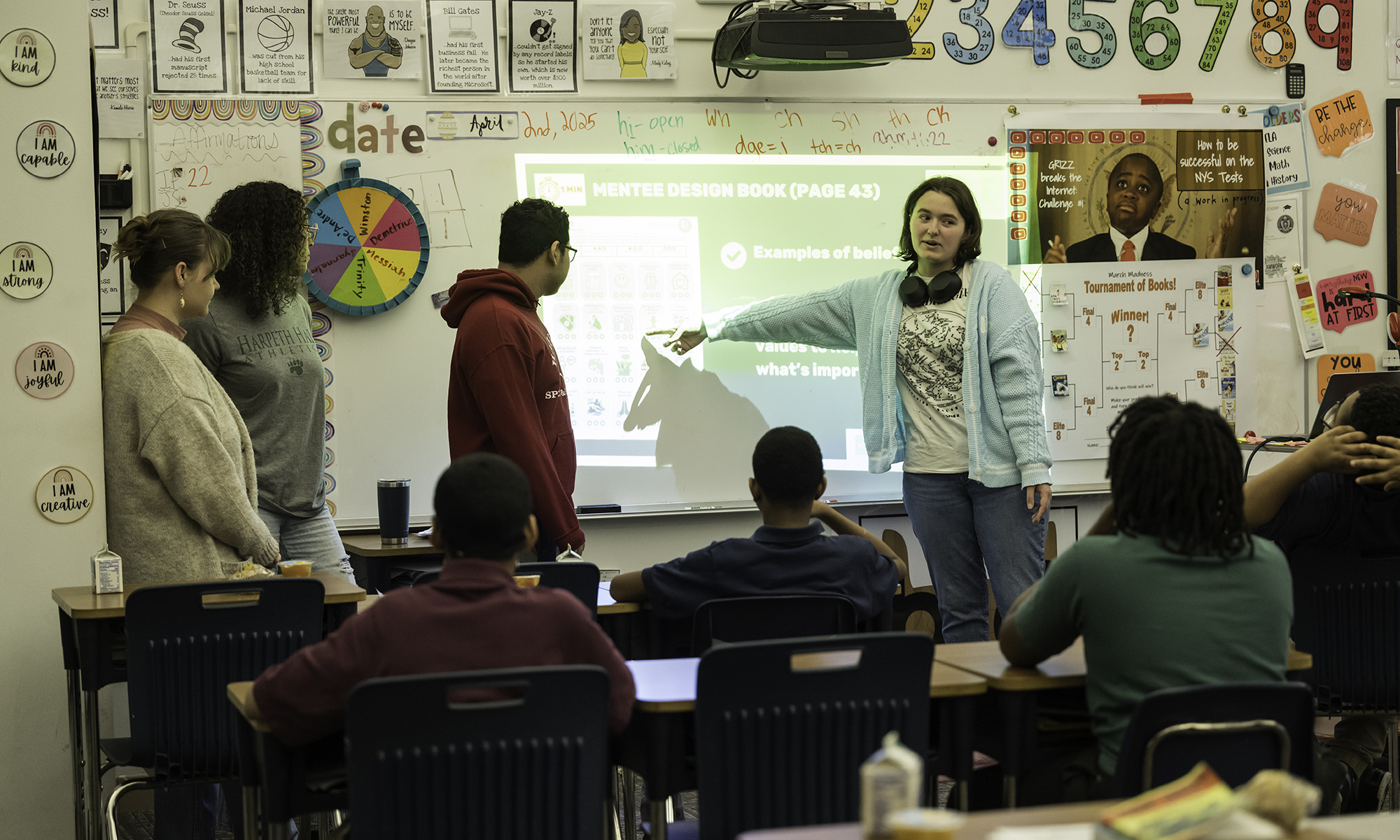

Sarah Bjornland ’17: Embracing her management superpowers

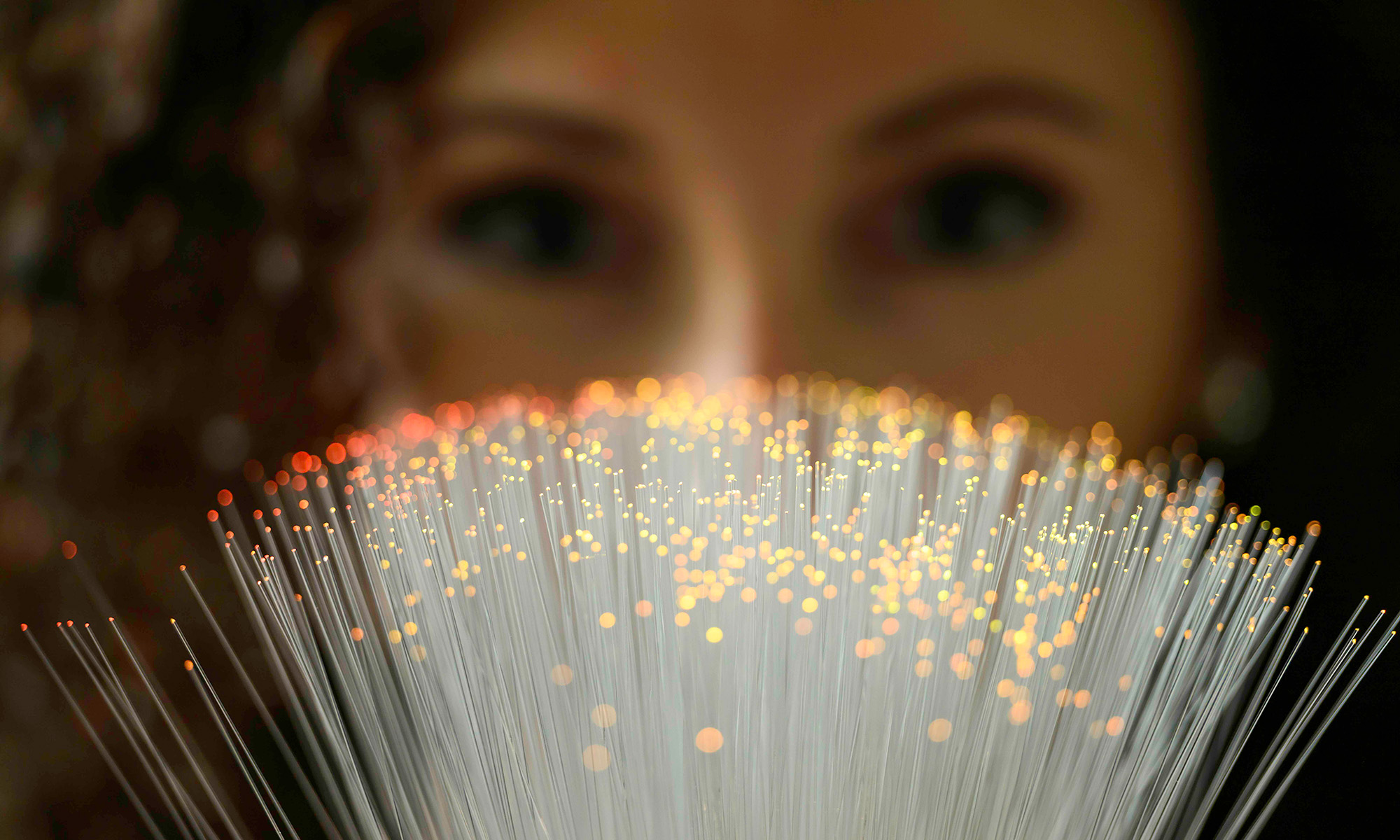

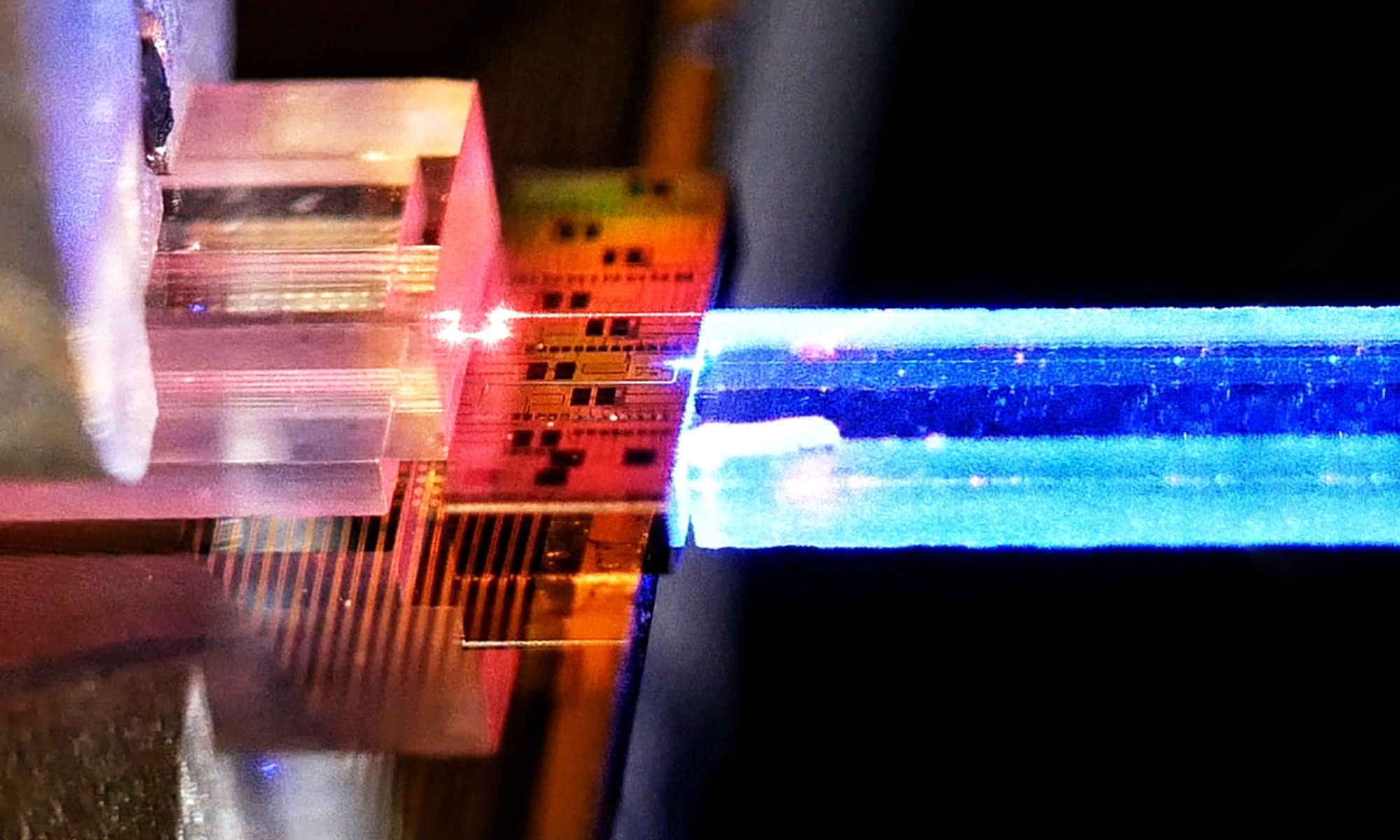

Meaningful connections with faculty and industry experts helped the Rochester graduate find her niche in the field of optics.

Rochester researchers on the growing concern of plastics exposure on human health.