Richard Feldman arrived on the River Campus as an assistant professor of philosophy in 1975. He eventually became a professor and chair of the department, and in 2006 he was named interim Dean of the College when longtime dean William Scott Green left to become vice provost and dean of undergraduate education at the University of Miami.

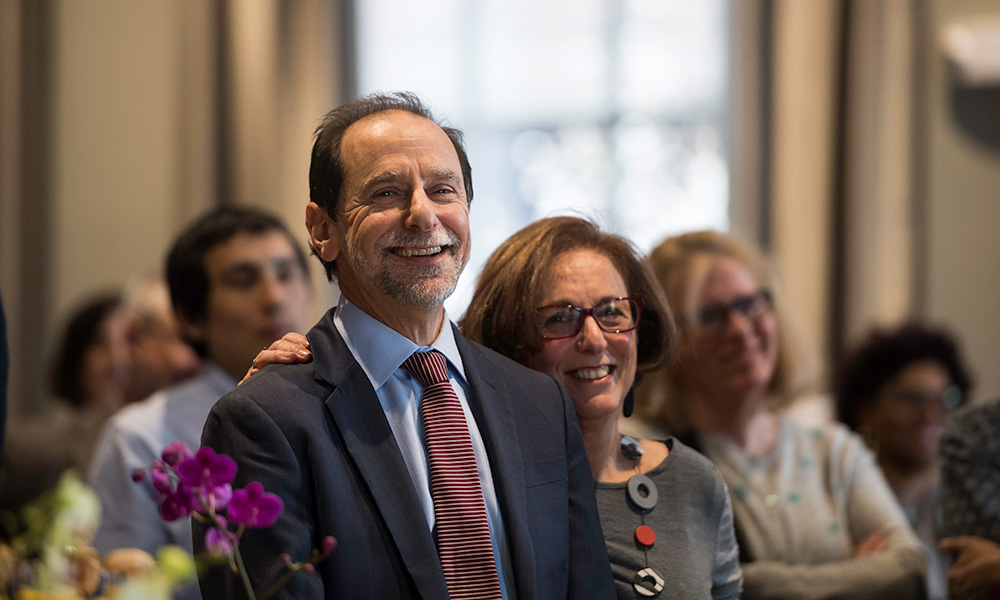

Feldman was appointed dean in 2007, and this past January, he announced he was stepping down at the end of the academic year. He’ll take a year’s sabbatical before returning to the University in 2018 as a philosophy professor.

“It’s hard for me to imagine the College without Rich Feldman as dean,” says Dean of Students Matthew Burns, who has worked with Feldman for 15 years. “While he leaves the College in a stronger place than ever, and has done as much as any one person could to ensure our future success, it seems surreal to imagine the place without him. He’s known for his great mind, his ethical leadership, and his sense of humility despite his tremendous abilities. It’s been one of the greatest privileges of my career to work with him.”

Beth Olivares, dean for diversity initiatives, says Feldman will leave a lasting mark at the College.

“A couple of colleagues noted that Rich models the best behaviors of the best leaders: he teaches by example as much as anything,” Olivares says. “I suspect there isn’t a corner of the College that hasn’t been changed for the better because of Rich’s leadership and attention to detail.”

Outgoing Students’ Association president Vito Martino ’17 says Feldman’s contributions to undergraduates have been “priceless.”

Feldman received his bachelor’s degree from Cornell University in 1970 and his doctoral degree in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1975. He lives in Rochester with Andrea, his wife of 42 years. Their daughter, Erica, lives in Philadelphia with her husband and two children.

How has the campus most dramatically changed over the four decades since you arrived?

One of the biggest changes is our connection to the Rochester community. When I started here, we were like an island, with the river and the cemetery surrounding the campus. There was very little connection to the Rochester community. The fact that students were in Rochester, New York, made very little difference to their experience. Now, with the growth of College Town, our academic engagement with the community, volunteering and internships, we’re a part of the community in a way we never were, unrecognizable from when I came here.

Why is it important for students to be part of the Rochester community?

Education beyond the classroom has a real impact on students’ lives. That kind of hands-on experience, interacting with the community, adds enormously to what they’re able to learn. Extending the classroom beyond the campus extends what students have the opportunity to learn about. Several years ago, people started to think online education might replace campus-based education. And it made me think, well, why are they here? What’s the value of them being here? There were three things: the ability to interact with one another on campus, the ability to interact directly with the faculty in research, and the ability to expand their education by interacting with the community. All help to enrich their education.

How have the students changed?

One way the student body has changed is the demographics. We’re more diverse in every way you can imagine: internationally, different racial groups, different religions. That’s one of our greatest strengths, provided we take advantage of it and students interact with one another and learn from one another. The other change that’s most notable has to do with technology and how it has changed the world. When I got here, there weren’t computers. You had to go to the library and read your books. Today’s students grew up with computers. It’s part of their lives. The way they interact with each other and the faculty and staff is so different.

You helped create and implement the Rochester Curriculum, which allows undergraduates to build a program of study based on their strengths and interests. Can you take us back to when you and others were fleshing it out and describe the philosophy behind it?

The curriculum committee meetings in the mid-1990s went like this: the standard model for the curriculum was to have a half-dozen categories of things and everyone has to do one of these and two of those. We thought it fostered a kind of superficiality, where you did an introductory thing here and there, checking off a list. Students would ask, “What do I have to do to be done with this?” Faculty too often found themselves teaching students who didn’t want to be there. Students were doing things they were forced to do. They weren’t engaged and weren’t learning enough. We also thought there was no convincing rationale for what set of things students were required to take. We could agree that it would be nice if they knew a little chemistry, and some biology, and some economics, and so on, for every discipline. But we couldn’t require some of everything. Our conclusion was that we should pick just a few broad categories and let students choose what they’re interested in. It will add breadth to their education, but they’ll own it in a different kind of way. It seems to me it has worked extremely well. Very few universities have something like this, and nobody I know has exactly this.

You placed a great emphasis on internships and study abroad programs. What’s the impact of this?

To prepare students for success in the world after they graduate. Employers say they want some kind of disciplinary expertise, but they also want people who are problem solvers and are able to communicate and interact with others and work in teams. In a great many cases, companies are established worldwide. Students gain those types of experiences through internships and studying abroad. In addition, studying abroad provides students with an opportunity to engage deeply with another culture, thereby building skills that will benefit them in the globally connected world into which they will graduate.

You played a lead role in planning the renovation of the Frederick Douglass Building, now Douglass Commons, as a student hub. Why was it important to have this revitalized building next to Wilson Commons, which opened the year after you arrived?

It connects to the point about the diversity of the campus. It’s effective if students interact with each other, and that’s increasingly a function of the kinds of spaces we offer. One impact of technology is that it makes it very easy to sit in your room and stare at a screen. That makes community spaces more important. A space like Douglass fosters accidental connections among students who might otherwise not interact with one another. The importance of community spaces like Douglass and the library have grown over time. It’s what Douglass is all about. Before Wilson Commons, the student hub was Todd Union, and there was a guy in the basement making hamburgers (where the post office is now). Wilson Commons is a beautiful building, and it’s played a great role on campus. But if you think about the purpose of a student center—a place where students can meet and events can happen—Wilson Commons is a big open space. There’s not a lot of floor space. It failed to serve that purpose as well as it might. Douglass fixes that, and we’re trying to link the two buildings as much as we can and think of them as a Campus Center. Together they make it all work.

You served as co-chair on the Presidential Commission on Race and Diversity. How do you view the racial climate on campus?

Overall, there’s a great deal of respect, acceptance and interaction among students. But at times there are problems. There are circumstances in which minority students and various groups of students feel excluded and unwelcome. We work very hard to try to correct that, but things happen that are less than ideal. I’ve been pleased by some things that have happened since the commission was started. The We’re Better Than That anti-racism campaign has brought a good number of faculty, staff, and students together. There is a lot of good-will in the campus community. But we need to continue to work to help people talk about difficult things in thoughtful and respectful ways. We can do always better, but the direction is right.

What other challenges remain for the College?

There are different kinds of challenges. From the administration’s perspective, there are challenges about continuing to attract and enroll the strongest students, issues about affordability of college and being able to address them. The structure of the curriculum, the offerings, it’s never a finished product. You’re always adapting. Years ago, you went to college, you studied something and got a degree, and had confidence that something would work out. We have to be more intentional now in understanding what skills our students need and keep getting better about making sure our education equips students for the world they’re entering.

If you never moved to higher education, what would you be doing today?

I’ve thought about that. It’s hard to know. My guess is I would have gone into law.

When did you know you wanted to be a professor?

Not until late in college. I started college as an engineer. I did well in math and science in high school, and people said ‘You’re an engineer.’ I didn’t know what engineering was, but I applied to engineering schools. I got in and pretty quickly learned I didn’t want to do that. I switched to physics for awhile and then went into political science. As a junior, I took a philosophy course, because my older brother at that point was finishing grad school in philosophy and I wanted to know what he was doing. I thought it was the hardest and most interesting thing I’d ever encountered. So I decided to make it my major, but then I went through this “Is it cool to do what my brother does?” It was senior year in college that I really decided philosophy was what I wanted, and I went on to grad school.

Being the dean of a college must be stressful. What are your stress relievers?

I like to run, I like to bike, my wife and I enjoy movies . . . I get together with friends. Those are the main things. One hobby I have is growing orchids. I intend to get more involved with that. As a kid, I played bridge a lot. I may get back to that.

You were named the Romanell-Phi Beta Kappa Professor in Philosophy for 2017-18 for your contributions to the field. You’ll present three lectures this fall that are open to the public. What will you be talking about?

The lectures will broadly be about topics on rational argument and public discourse. Kind of an interesting topic to think about these days.

Are you looking forward to returning to the faculty in 2018?

I am. The pace and style of the dean’s world is very different from the faculty. I’ve absolutely loved this job. It’s been enormously gratifying, rewarding, and exciting. The pace of it is intense. I’m looking forward to a change, but I know I’m going to miss being dean.

Will you do any traveling during your year away?

Yes, I have a philosophy conference and talks in Italy, a week-long seminar in Cologne, Germany, and my wife and I plan to spend a month in Philadelphia where our grandchildren and their parents live. And we’re thinking about a trip to Cuba.

What will you miss most about being dean?

I think the interactions with the students, my colleagues in the dean’s office, and the college staff I work closely with. The thing I’ve come to appreciate as dean in a way I didn’t before is how much all the people on the college staff contribute to the education of our students to make it all work. All the things beyond the classroom that contribute to the students’ experience have really made an impression on me.

Finally, what’s your proudest achievement as dean?

Early on in my time as dean, we looked at the graduation rates of our students. They weren’t what we wanted them to be, and we set out to find out why, and what we could do to improve them. They’ve gone up notably, and I’m delighted by that. Everything that happens on campus contributes to the success of students: the classes, co-curricular programs, the buildings. The improvement is a function of lots and lots of different things.