A new study from the University of Rochester sheds light on how parents and caregivers of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) can best help their kids, and at the same time, maintain peace at home and at school.

“Children with FASD often have significant behavior problems due to neurological damage,” says Christie Petrenko, a research psychologist at the University’s Mt. Hope Family Center.

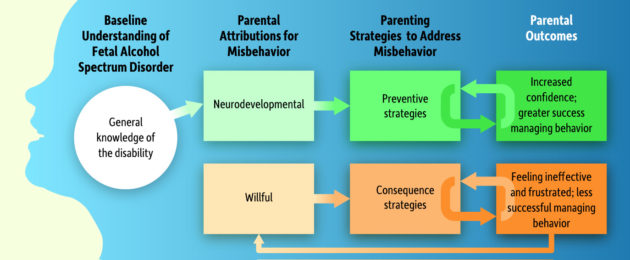

Petrenko and her colleagues found that parents of children with FASD who attribute their child’s misbehavior to their underlying disabilities—rather than to willful disobedience—tend to use pre-emptive strategies designed to help prevent undesirable behaviors. These strategies are likely to be more effective than incentive-based strategies, such as the use of consequences for misbehavior, given the brain damage associated with FASD.

The study included 31 parents and caregivers of children with FASD ages four through eight. Petrenko and her team analyzed data from standardized questionnaires and qualitative interviews that focused on parenting practices.

Petrenko says that the study, which is published in Research in Developmental Disabilities, shows that educating families and caregivers about the disorder is critical.

People with FASD often have problems with executive functioning, which includes skills such as impulse control and task planning, information processing, emotion regulation, and social and adaptive skills. As a result, they are at high risk for school disruptions and trouble with the law.

Parents who use pre-emptive strategies “change the environment in a way that fits their child’s needs better,” says Petrenko. “They give one-step instructions rather than three-steps because their child has working memory issues. They may buy clothes with soft seams if their child has sensory issues, or post stop signs to cue the child to not open the door. All of these preventive strategies help reduce the demands of the environment on the child.”

The study also shows that parenting practices correlate with levels of caregiver confidence and frustration. Families of children with FASD are frequently judged and blamed for their children’s misbehavior. Parents and caregivers who are successful in preventing unwanted behaviors have higher confidence in their parenting and lower levels of frustration with their children than parents who counter unwanted behaviors with consequences after the fact.

Petrenko says that evidence-based interventions for families raising children with FASD have been developed and show promise for improving outcomes for children and families. She and her team at Mt. Hope Family Center are continuing to further test these interventions and identify what strategies and approaches are most effective in getting evidence-based information to families.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.