We dug into the campus newspaper archives to trace the evolution of eclipse knowledge—and etiquette—over the last century.

There’s no shortage of advice on how to safely view the total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024. From guides on eyewear to telescope filters and vantage points to pinhole projectors, modern media has every angle covered.

So, what advice were people given about how to look at a solar eclipse the last time such an event plunged Rochester into darkness? Before the internet. Before smartphones. Before television. Before eclipse glasses were mass produced.

It was 1925 and Calvin Coolidge became the first president to have his inauguration broadcast on radio, F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby, and the National Spelling Bee debuted.

Here’s a look back at how The Campus, the student newspaper that preceded The Campus Times, advised the University community to view the total solar eclipse of January 24, 1925.

1. Make sure your timepiece is accurate.

Before the clocks on our computers and smartphones were synced up to atomic clocks embedded in GPS satellites orbiting the globe, no one really knew precisely what time it was.

People set clocks in rough approximation. They might have asked someone, “What time do you have?” and that person, looking at their wristwatch or pocket watch, might have replied, “Oh, about quarter to 3.” And, so, the time became 2:45.

During the last total solar eclipse in Rochester, wristwatches had just come into vogue, having been a holdover from soldiers in World War I, who affixed their pocket watches to their wrists in combat.

University physics professor Floyd Cooper Fairbanks was a stickler for time in his column in The Campus on how to view the eclipse. “If you have an accurate timepiece, recently checked, it will be worthwhile to record the exact time (of the total solar eclipse),” he wrote. “. . . If you have an accurate timepiece, the exact time of the beginning and ending of the totality should be observed.”

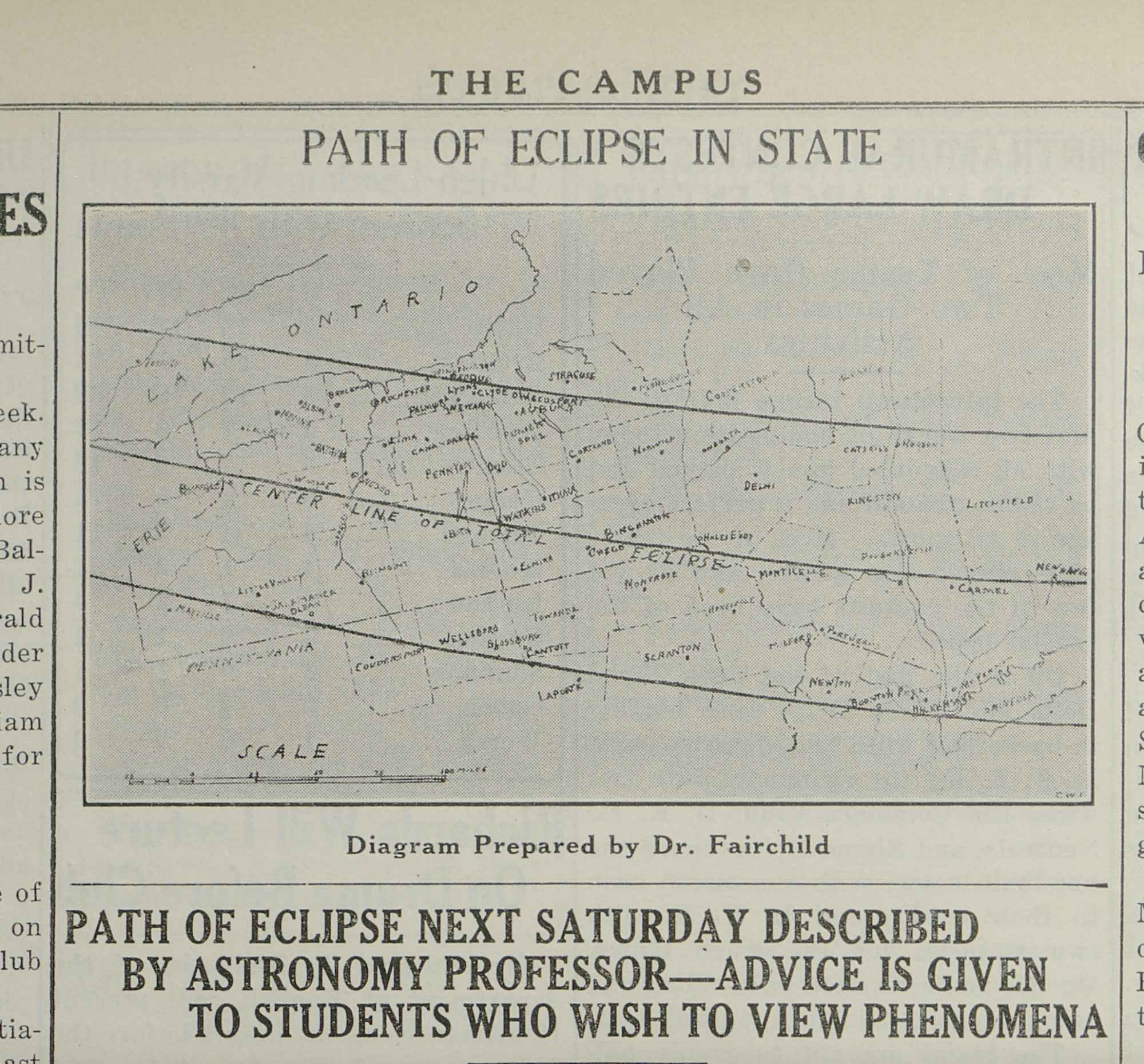

He suggested watching from a high hilltop and to look to the west for the path of totality—a shadow roughly 110 miles wide—fast approaching. “(T)he black shadow may be seen approaching at the tremendous speed of 1,300 miles an hour,” he wrote.

That’s a shadow about the size of Connecticut.

2. Enjoy the spectacular solar corona—but don’t ask what it is.

The last time Rochester was engulfed in a total solar eclipse, scientists had yet to settle on what made the solar corona so spectacular.

“The most striking object to be observed during totality is the corona,” Fairbanks wrote. “. . . There is no satisfactory explanation of the corona. The spectroscope gives evidence that its light is due to solid and liquid particles and luminous gases.”

Thanks to a landmark discovery by Rochester alumnus and astronomer William Harkness in 1869, scientists knew the corona comprised something other than the gases that made up the sun. They dubbed that something coronium.

But it wouldn’t be until observations made during eclipses in the 1930s that scientists realized what they thought was coronium was, in fact, iron—albeit with half of its 26 electrons missing. That indicated the corona was many times hotter than the sun itself. Today, scientists are still trying to figure out why.

3. Don’t use your opera glasses to view the eclipse.

There is no telling how many everyday people in Rochester had opera glasses at their disposal in 1925.

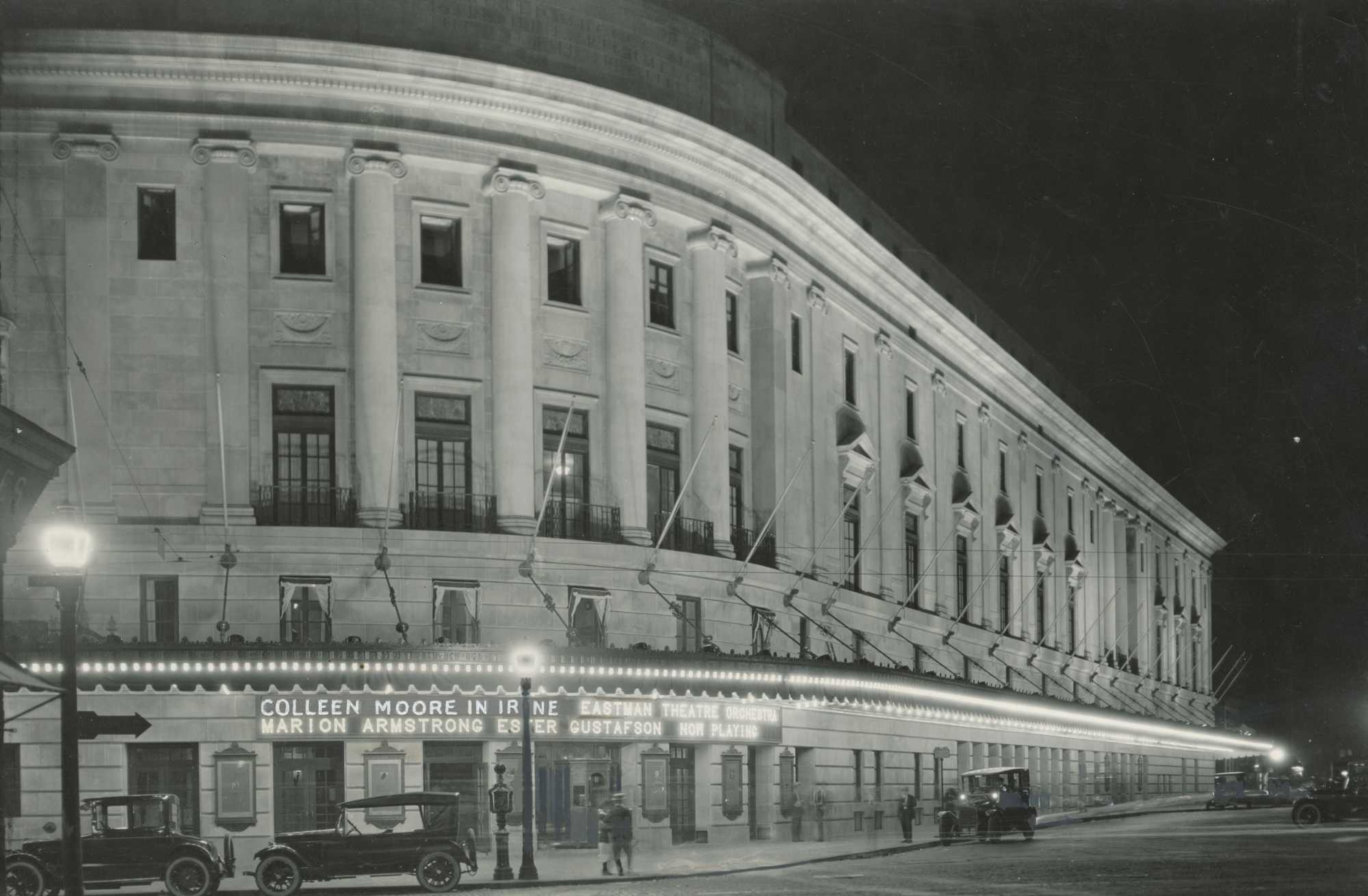

What we do know, though, is that the University’s Eastman School of Music and its Eastman Opera Theatre began in 1921, and that Eastman Theatre on Gibbs Street quickly became Rochester’s preeminent performance space upon opening in 1922.

Apparently, opera glasses were ubiquitous enough around campus that Fairbanks saw fit to warn in his column, “The sun should not be looked at through an opera glass or telescope while any portion of it is shining, unless the eyepiece is covered by smoked glass.”

But that bit about “smoked glass” is outdated. Using smoked glass to view solar eclipses had been popular since King Louis XIV of France covered his telescope with a piece of smoked glass to observe an eclipse in 1706. It reportedly fell out of favor in the mid-20th century, when doctors began documenting eye problems in children who used smoked glass to view eclipses.

How to look at a solar eclipse today

Do not attempt to view the upcoming eclipse with any eyewear that are not certified ISO 12312-2 compliant, the international safety standard for solar eclipse glasses. So, if you haven’t already, it’s time to put away the opera glasses, smoked glass, and even that older pair of solar eclipse glasses (here’s why).

Need a fresh pair? The University has you covered. Get yours here.