Although you can’t technically check out these volumes—ranging from a medieval anthology to a mid-20th century how-to guide—they’re still worth ‘checking out.’

Carefully preserved within the roughly three million volumes in the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries are a couple dozen rare books that explore astronomy and solar eclipses.

To celebrate the 2024 total solar eclipse on April 8, Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian, will display some of the works in Rush Rhees Library. Anyone who misses the display can request to see the books at any time.

These volumes, some published more than 500 years ago, can’t be checked out, but they’re still worth checking out. Here are seven titles that offer a taste of what awaits.

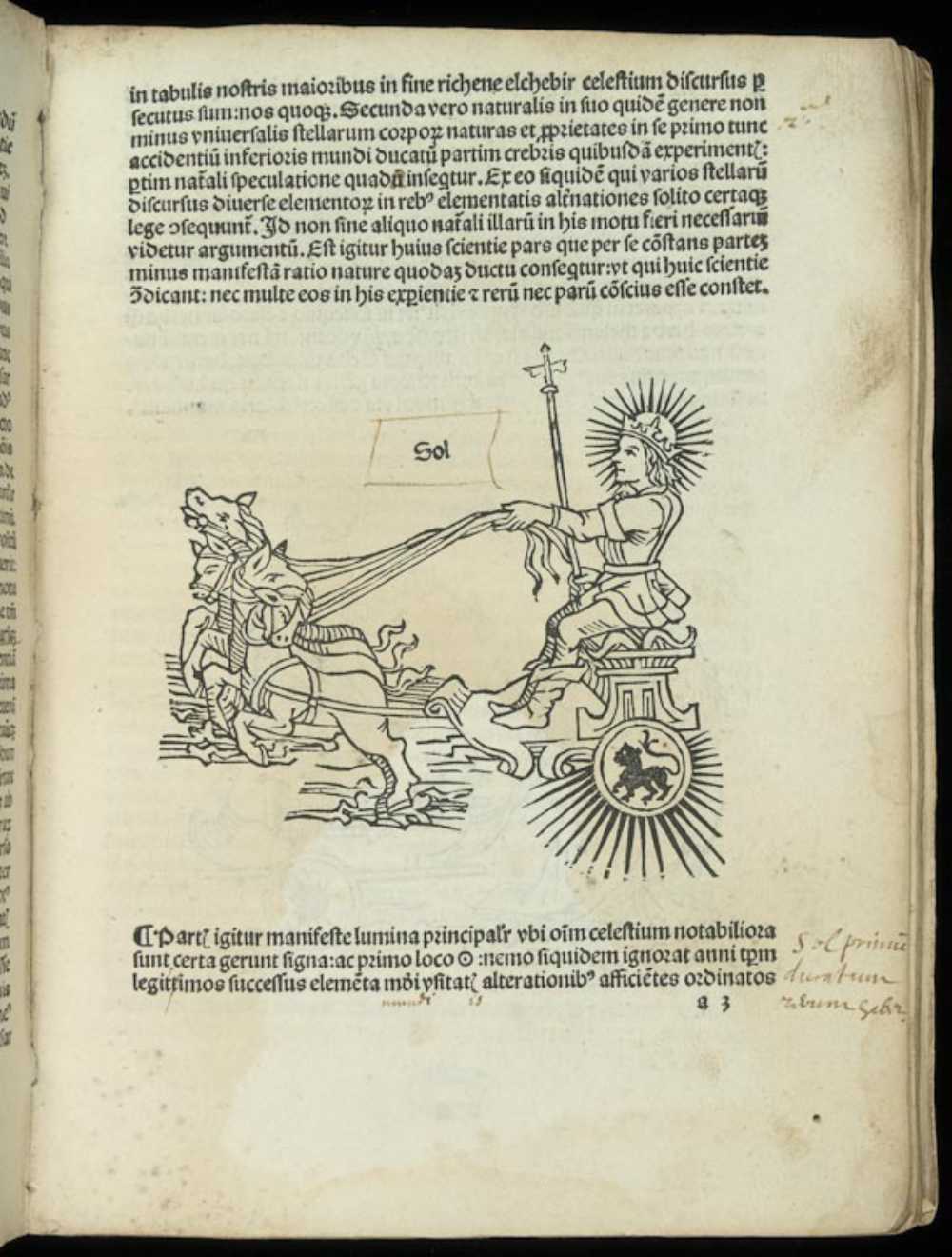

Introductorium in Astronomiam by Ja’far Ibn Muhammad Abu Ma’shar (Abumasar) Al-Balkhi (1489)

Astronomer and astrologer Abumasar, who was born in what is now Afghanistan, penned this anthology of his observations of the cosmos between 849 and 850. This copy was printed in 1489 and is one of the oldest of the astronomy books in the archives.

Introductorium in Astronomiam (The Great Introduction to the Science of Astronomy) consists of eight books dealing with subjects as varied as how the planets in our solar system influence Earth and the relations between zodiacal signs.

This treasure was bequeathed to the University by alumnus William Harkness, who made what astronomers consider a “landmark discovery” during a solar eclipse in 1869.

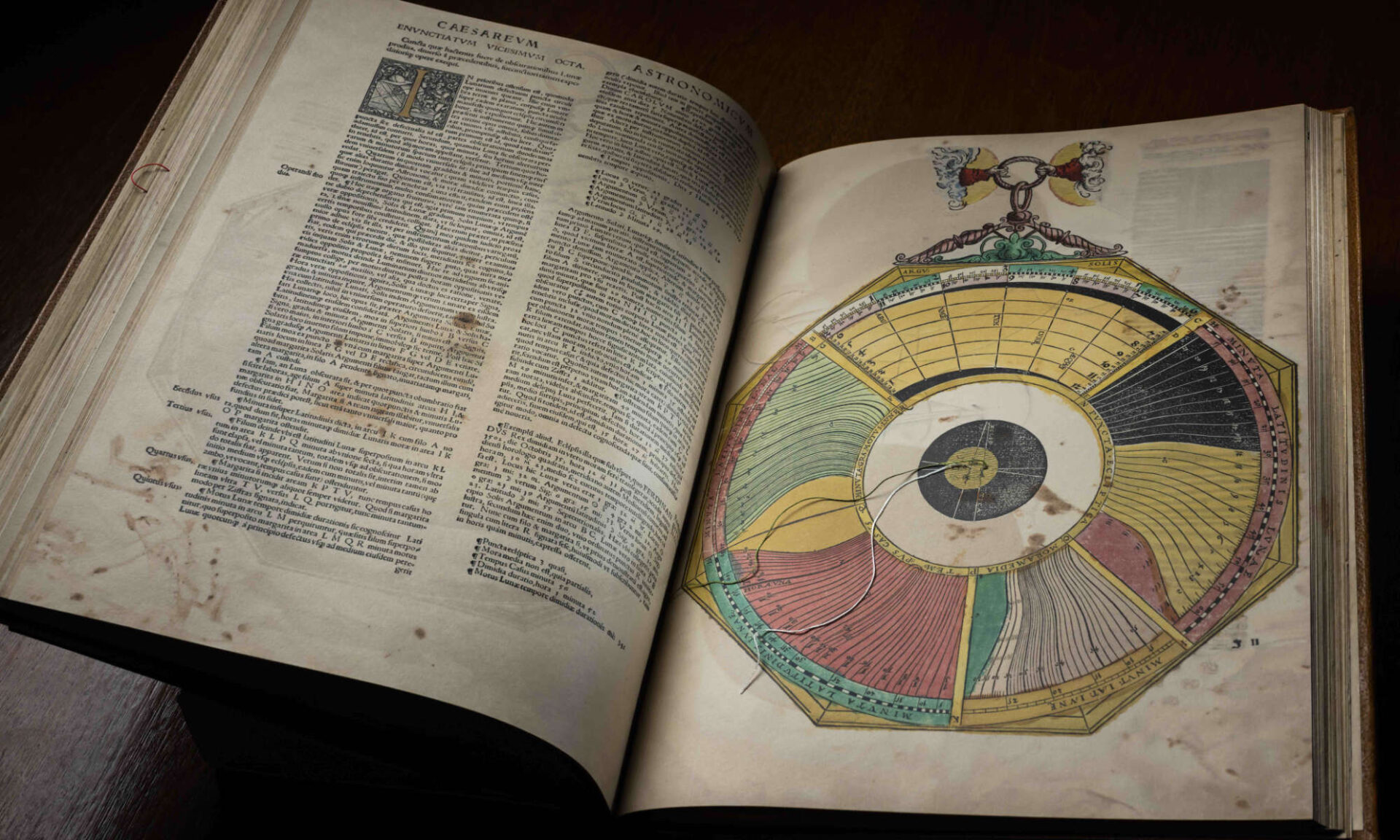

Astronomicum Caesareum by Petrus Apianus (1540)

Holy Roman Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand I commissioned German humanist Peter Apian to complete this work, whose title translates to “The Emperor’s Astronomy.” (The ego of a holy Roman emperor apparently knows no bounds.)

The University of Rochester’s copy is not an original, but rather a facsimile. It is worth a look, though, because of its intricate and colorful volvelles, a set of overlapping paper disks that the reader can rotate to calculate astronomical information. Volvelles are like a cross between a primitive computer and a pop-up book.

The volvelles of Astronomicum Caesareum rely on the debunked geocentric model of the universe, which places the Earth at the center of it all. But they are nevertheless something to behold.

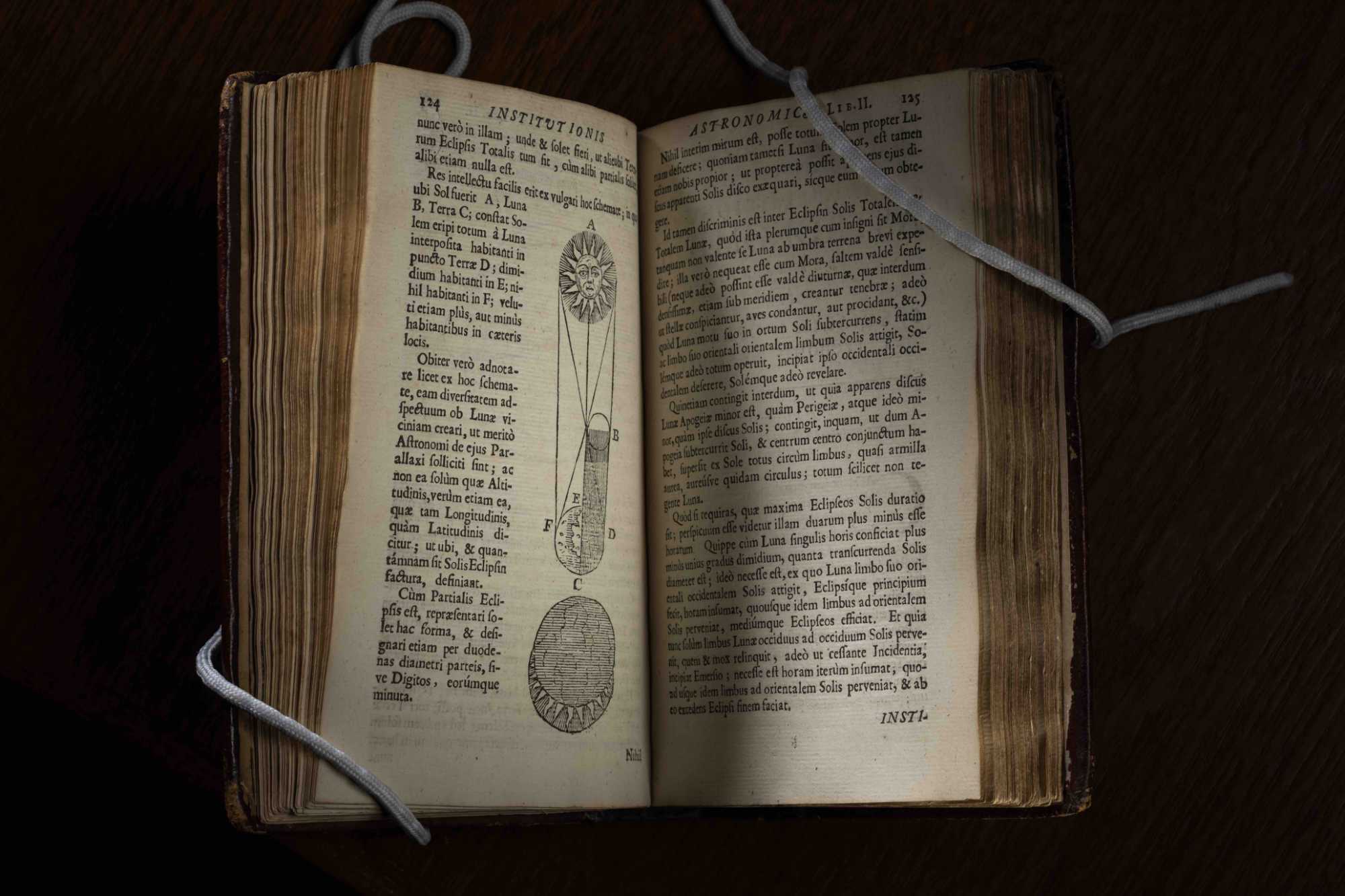

Institutio Astronomica by Petri Gassendi (1653)

You won’t be able to read this work by French astronomer and mathematician Pierre Gassendi unless you know Latin. But you can marvel at its illustrations of solar eclipses and at how far science—and graphic design—have come in the last 400 years.

Institutio Astronomica was based on a series of lectures Gassendi gave in his day and is considered one of the first modern astronomy textbooks. Very cool.

Also cool: Gassendi made many of his observations through telescopes given to him by Galileo, and in 1631 was the first person to observe and record a special kind of eclipse in the transit of Mercury across the sun.

Young Ladies’ Astronomy by Montgomery Robert Bartlett (1825)

Opening this textbook is as much a trip into the heavens as it is into history.

Underlying the premise of this teaching tool—whose full title is Young Ladies’ Astronomy: A Concise System of Physical, Practical, and Descriptive Astronomy Designed Particularly for the Assistance of Young Ladies in that Interesting and Sublime Study—is the stark reality that astronomy instruction in American classrooms of the early 19th century was typically reserved for boys.

The author wrote in his introduction that he had collected and arranged the materials while teaching a class of girls in 1820 in “elementary studies.”

The book, which was printed in Utica, New York, includes ringing endorsements from Governor De Witt Clinton, and Theodore Strong, a math and philosophy professor at nearby Hamilton College, who wrote: “I do therefore most cheerfully recommend the work, not only to the Young Ladies of our country, but also to all others, and particularly to the instructions of our schools.”

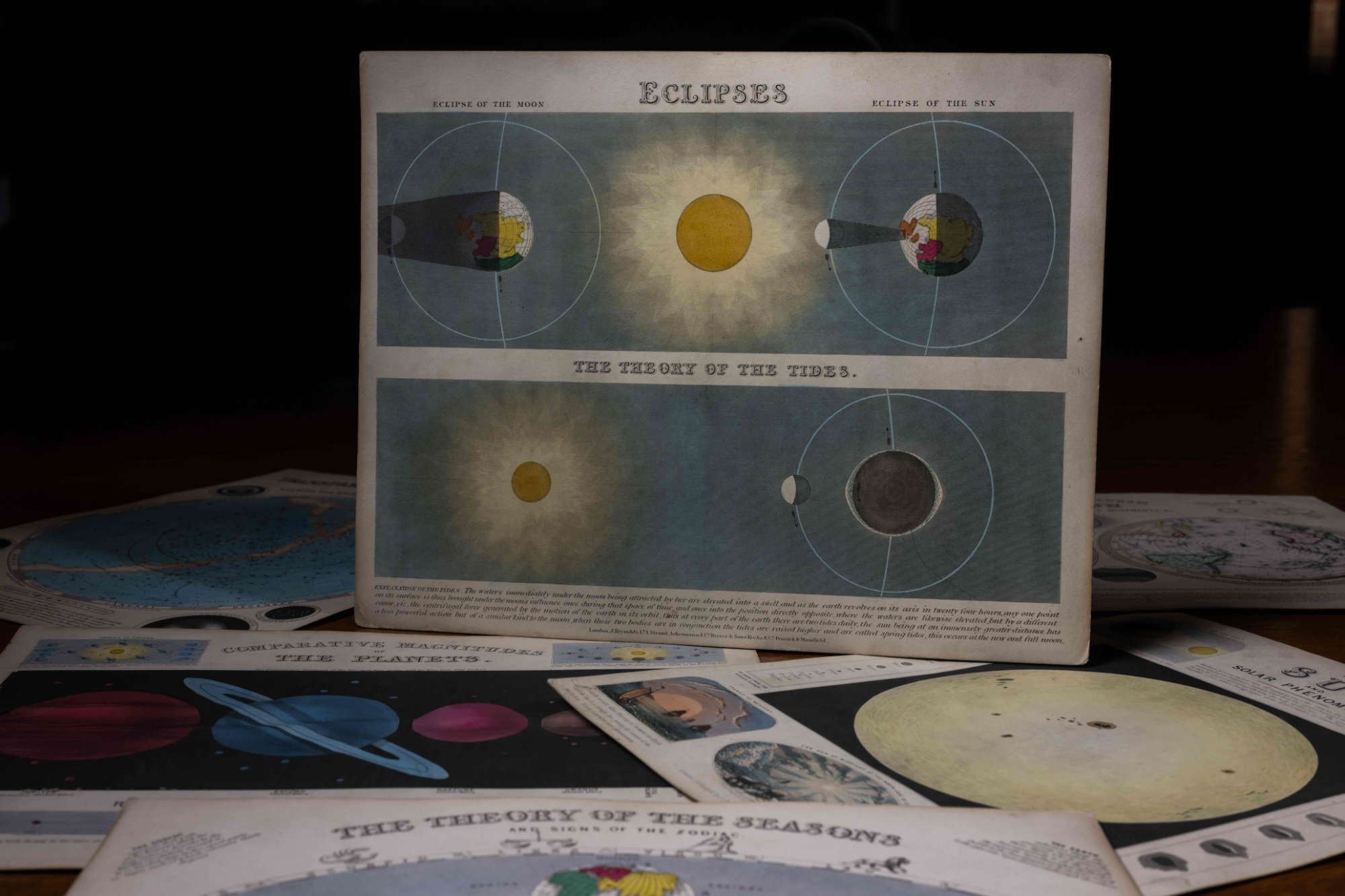

Diagrams of Geology, History, and Physical Geography by James Reynolds (1849)

Tucked inside this simple, blue Victorian cloth folder are 18 hand-drawn diagrams bursting with color on cardstock for display in an educational setting.

“That was your PowerPoint of the day,” says Mead, the University archivist. “They might have been pinned up on the wall of a classroom.”

As the title of the volume suggests, the diagrams cover topics in geology, history, and geography, including the comparative sizes of the planets of the solar system, the changing of the seasons, and, of course, eclipses.

The best part? Four of them are so-called “transparent diagrams,” constructed with cut-outs on translucent paper that, when held up to the light, illuminate the artwork. You won’t need special glasses to safely view these brilliant images, though.

Has the Earth a Ring Around It? by Dr. Frank Gerald Back (1955)

This heartfelt ode to a pal is a must-read for any Albert Einstein enthusiast.

Author Frank Back, an optical engineer known as the “Father of the Zoom Lens” for his creation of a zoom lens widely used in television and film, dedicated this book to his close friend Einstein, who had helped arrange for Back to “chase” and photograph a total solar eclipse from aboard a military jet in 1955.

Back had intended to tell Einstein all about his journey upon his return, but Einstein died just as Back had embarked for The Philippines to catch the aircraft that was to shadow the eclipse.

“This book is a factual report which shall be printed instead of being told to Albert Einstein,” Back wrote in the introduction. “It all started in Minneapolis on July 30, 1954 5:08 A.M., with a total eclipse of the sun of no scientific significance.”

The book is illustrated with photographs of Back and Einstein, lending an intimacy to the relationship that Back’s words alone don’t capture.

Solar Eclipse Photography for the Amateur by Eastman Kodak Co. (1959)

The total solar eclipse covering parts of the United States on April 8 is an opportunity for amateur and professional photographers alike to capture a celestial phenomenon.

Lots of websites offer advice on snapping a picture of the eclipse, with perhaps the most reliable among them being the American Astronomical Society’s extensive guide to photographing the event with a standard camera or smartphone.

But before the internet and smartphones, there was this handy six-page booklet published by the Eastman Kodak Company of Rochester. The booklet was once ubiquitous, but it wasn’t built to last and went out of print years ago, making intact copies hard to come by nowadays.

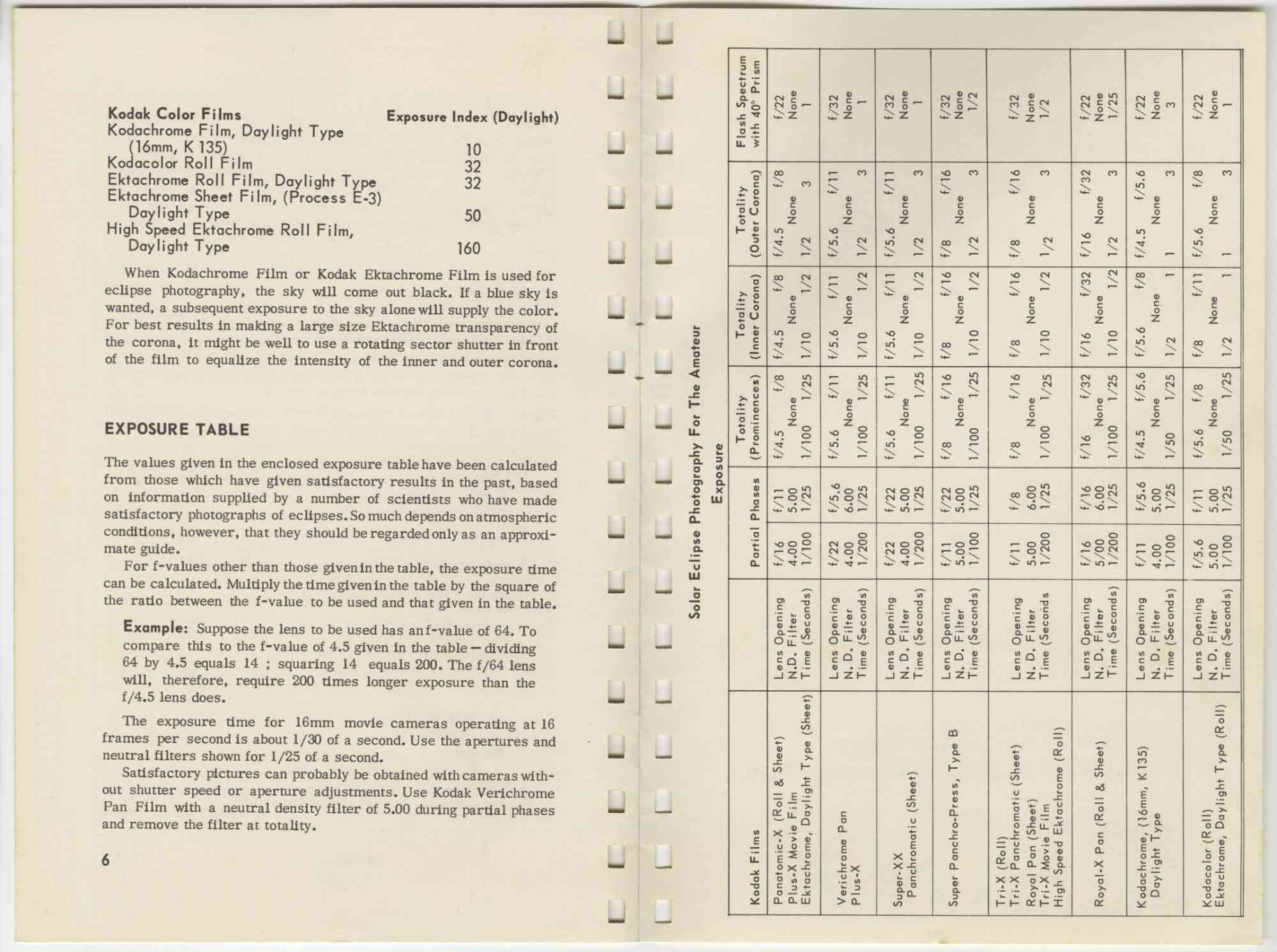

Perusing this little number, with its table of exposure times, is a rare chance to glimpse how previous generations of shutterbugs learned to make images of eclipses properly and safely.

The booklet was gifted to the University of Rochester by the late Charles Carlton, a longtime University professor of French and Romantic linguistics.