The new Golisano Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Institute will drive transformations in IDD research, training, care, and advocacy.

When Lisa Latten’s son, Ian, was diagnosed with autism at age two and a half in 2007, what she remembers was her fear. “I thought, ‘What am I going to do?’ I had this overwhelming need to close ranks—to protect my child, to protect myself,” she recalls. “As a parent, you recognize that the world is not set up to support our kids, accept our kids, and love our kids.”

About Tom Golisano

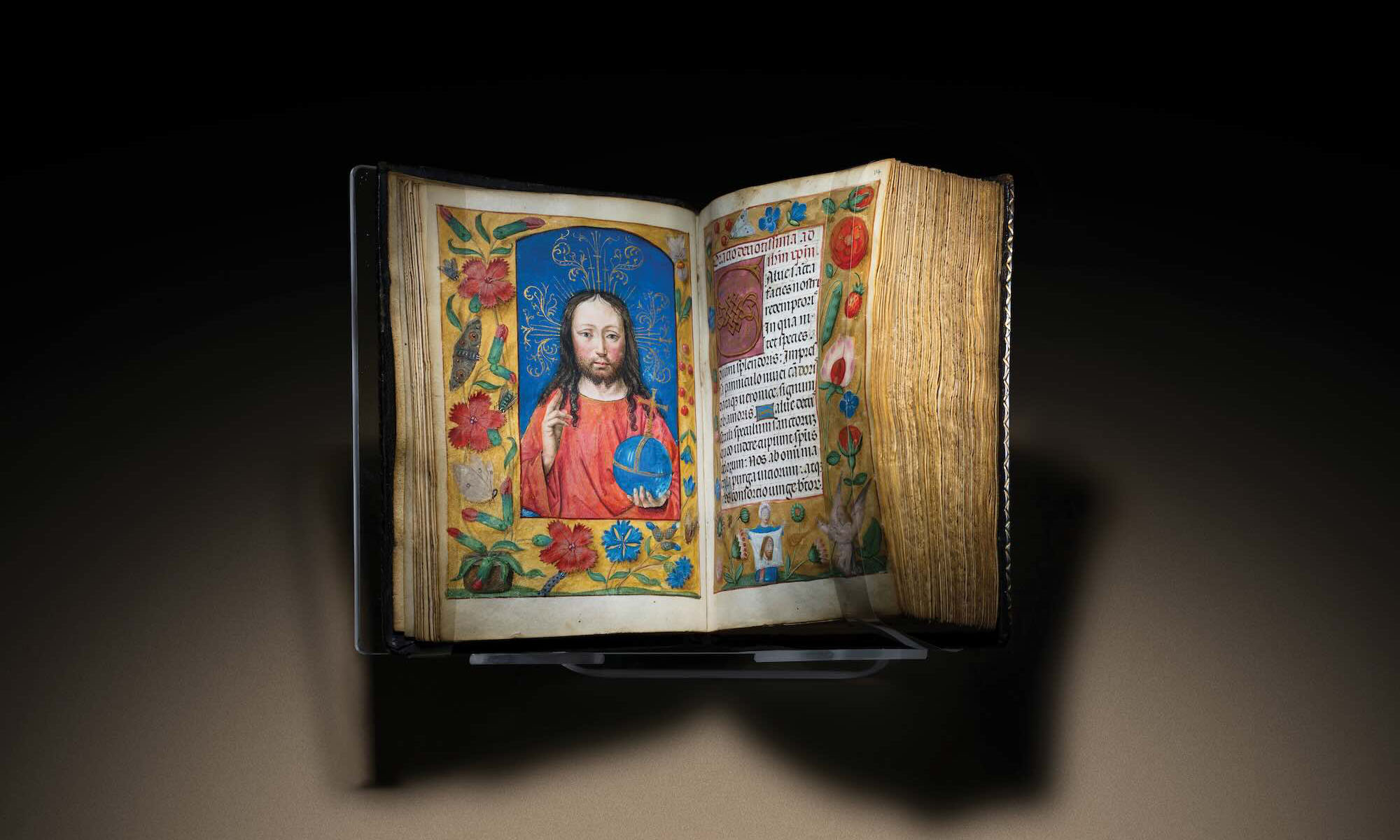

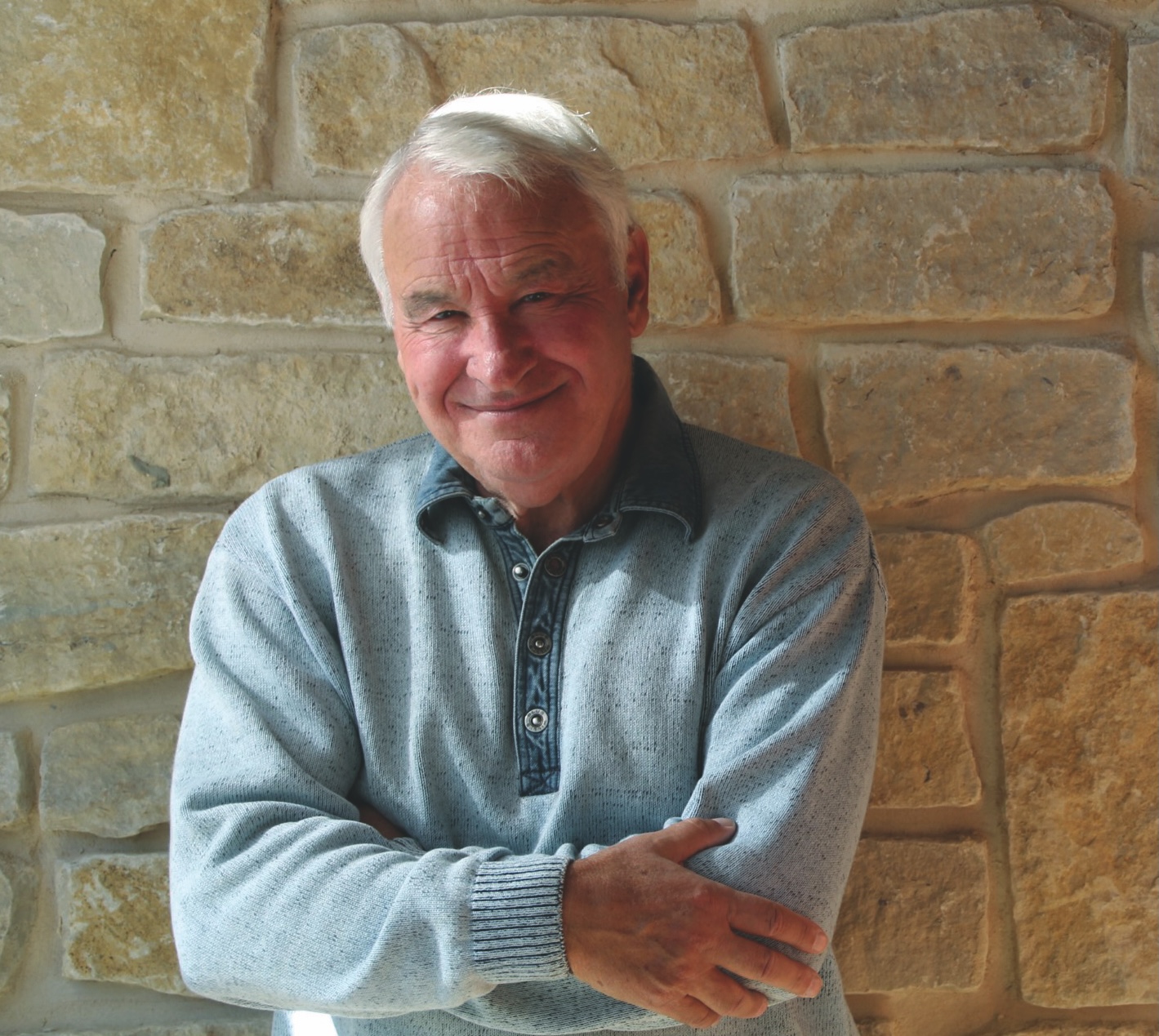

Golisano’s $50 million gift to create the Golisano Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Institute isn’t the only major commitment he’s made in the last several months. In October, Inside Philanthropy showcased the extraordinary commitments the Rochester area native is making to Upstate New York this year. Read an excerpt.

In the intervening years, she has found caring doctors and dentists at the University of Rochester Medical Center who are skilled at working with Ian and other children who have intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). She’s witnessed a significant jump in awareness, as the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder quadrupled between 2000 and 2020. And she and her son have benefited from research and new approaches to care, including many pioneered and honed at Rochester.

Latten herself has helped propel this change: today, as a clinical administrator in the Medical Center’s Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, she helps families who have concerns about their child’s development connect with the resources they need. In addition, she often informally provides emotional support to parents who find themselves in the spot she was in 17 years ago. “Sometimes, families just want someone to say, ‘I’ve been that parent, I really do know how you feel,’ ” she says.

The University of Rochester has long been known as a leader in the field of IDD. It is one of just eight institutions nationwide with three major federally funded programs that support IDD-linked training, research, and advocacy. Over the past decade, the University has invested more than $80 million in IDD research and care, opening new facilities and expanding research programs. Its pediatric clinicians work with more than 15,000 IDD patients annually, and the school’s dentistry program cares for more than 2,000 patients.

And thanks to a recent $50 million gift from businessman and philanthropist Tom Golisano, these efforts will accelerate even further. Future plans include a new facility, the Golisano Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Institute, that will bring together more specialists and researchers to help individuals with IDD and their families thrive. They also include increased funding and collaboration for research, training, care, and advocacy.

The Killian J. and Caroline F. Schmitt Chair in Neuroscience and director of the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience John Foxe, who has been tapped to lead the new institute, calls it an “extraordinary investment” that will help fuel Rochester’s growth from its already lofty perch among IDD-focused institutions. “It will allow us to paint on an even bigger canvas,” he says.

Latten knows that the time has never been better: even as she’s seen the positive changes over the course of her son’s life, she knows challenges remain. For example, Ian, now 19, is aging out of pediatric care. While this is part of a positive development nationwide—individuals with IDD are living longer, healthier lives than ever before—it also means that there are fewer options that will support his ongoing care and thriving.

Even more than that, Latten is ready for a world that will fully embrace her son as he is. “When I think about the world I want to see, or the world that we will leave after I’m gone, I think: ‘Don’t we want a society that is inclusive for our most vulnerable people, where people can get what they need?’ The work we can do is about building that world. I hope that is what a U of R alum would want. The possibilities are right here in our backyard.”

We highlight five pressing challenges in the field of IDD—and how the institute’s researchers, clinicians, patients, and advocates will work toward solutions.

Challenge #1:

Researchers in the IDD field face physical barriers to collaboration.

Solution:

Bring experts doing IDD-related research across disciplines together in one place.

INSIGHT: Across the University, researchers are bubbling with ideas that have the potential to transform IDD care. Currently, more than 100 investigators at the University are focused on IDD research, with more than 200 research projects in process.

Among other things, these projects aim to shorten patients’ hospital stays, illuminate differences among IDD populations at the molecular level, and prevent common complications in IDD individuals, like pneumonia, through targeted interventions.

The diversity and sophistication of the work is one reason that Rochester is one of only 15 nationally recognized Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Centers. The designation recognizes institutions with expertise across basic, translational, and clinical research.

But the complexity of the research increasingly demands that experts work together to make meaningful progress, says Mark Taubman, CEO emeritus of the Medical Center and former dean of the School of Medicine and Dentistry.

“It used to be that individual laboratories could do everything, but now you need to pull in people who have expertise in specific areas,” he says. “For some brain imaging projects, for example, you need multiple people who understand molecular biology, imaging, and clinical manifestations of complex disease.”

When researchers have offices and labs in a single, signature space, it creates what Foxe calls “the geography of integration.” That’s what he expects the new institute will bring about.

“When you get all the folks from various entities into one space,” he says, “you can have conversations over a pot of coffee, or pop your head around the corner to ask a question of somebody. It will get rid of inertia and barriers.”

Challenge #2:

Care for individuals with IDD is fragmented across many sites and services.

SOLUTION:

Offer coordinated expertise all in one place.

INSIGHT: Long waiting lists for services split across many sites and specialties are among the many frustrations that families of IDD individuals face when seeking care for their loved ones.

It’s a topic that Carrie Baker ’24W (MS), the mother of Ella, a 21-year-old with Down syndrome, knows intimately. “So many people with disabilities, Ella included, see many different specialists. It’s important for their health and longevity for those specialties to understand not just the disability, but to communicate with one another,” says Baker, who is also the director of the Family Experience Program in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

Just as it addresses barriers to research collaboration, the institute is designed to replace fragmented approaches with holistic care.

Dennis Kuo, chief of the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, says there are useful models that have been developed in other areas of medicine. “We know that there are models of integrated care where the healthcare system has taken a good look at this issue, like oncology,” he says. “I do think we can solve this. It’s important, because families are asking for more than just solutions to symptoms and challenges. They want to make sure that they, and their children, really have the chance to thrive.”

Challenge #3:

There are too few clinicians who have the expertise to treat the many patients with IDD. They are often centered in a few key hubs, requiring families to uproot their lives to get the care they need.

SOLUTION:

Develop leaders in the field with deep expertise—while also ensuring that all of our medical students get basic training to care for individuals with IDD.

INSIGHT: Professor emeritus of pediatrics Steve Sulkes spent almost his whole career working with individuals with IDD—but he admits as a medical student, his knowledge of developmental disabilities was limited, and his empathy was minimal. “I had a terrible attitude,” he says. But when he was able to go out into the community and meet these individuals as they were living their normal, daily lives, he was instantly transformed: “It changed my whole focus.”

That’s a big reason that the School of Medicine and Dentistry offers a family experience that connects families and individuals with developmental disabilities with medical students and other learners. “It puts you up close and personal, not as a professional, but as a learner, with people who have developmental disabilities,” he says. “It changes people’s attitudes very quickly.”

Other relatively straightforward types of medical training—such as ensuring that care providers ask how an individual with IDD prefers to communicate—can open up more opportunities for practitioners at every level to support basic care for people with IDD. “More than 10 percent of the population has a developmental disability, but nowhere close to 10 percent of curriculum time goes to thinking about how to work with them,” Sulkes says.

Rochester will also continue to operate the federally funded Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and related Disabilities (LEND), a program that has trained thousands of professionals since its inception in 1994. “People in different specialties receive general training, but never really learn how to work with the disability community,” says LEND director Laura Silverman ’02 (MS), ’07 (PhD), ’08M (Flw). “Our program is unique because we train specialists and advocates to become leaders in the field of developmental disabilities.” Over the years, LEND has trained professionals in 14 different disciplines, including doctors, psychologists, dentists, and educators.

As Rochester experts continue to work on these projects, director of the Strong Center for Developmental Disabilities Suzannah Iadarola says that she and others are particularly excited about the ways that the institute can help bring together both experts at Rochester and the disability community beyond the University. “We began working on a strategic plan before we knew there would be a new institute, so we have a strong head start and template for how we’ll approach this type of unification,” she says.

Challenge #4:

Dental care is especially hard for people with IDD to access and is their number one unmet health need.

SOLUTION:

Build on the Eastman Institute for Oral Health’s history of innovations in care for people with IDD by expanding specialty care and resident training.

INSIGHT: Visiting a dentist for complex oral care can be anxiety provoking for any patient. For patients with IDD, many of whom have a heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli, that anxiety can be a reason to avoid necessary care. The Eastman Institute for Oral Health (EIOH) has been providing care for people with IDD for 45 years through community clinics and a custom-designed mobile unit and, in that time, has introduced a number of adaptations to meet the needs of these patients. Chief among those is a set of techniques to help reduce patients’ anxiety while slowly building trust. As a result, EIOH has been able to provide care without anesthesia in many instances. Hundreds of EIOH residents have been trained in the techniques and are applying their skills throughout the US and around the world. An existing specialty clinic, renamed Golisano Specialty Care, and additional oral health care facilities in a completed IDD institute “will allow us to significantly increase our impact locally and globally,” says EIOH Director Eli Eliav.

Challenge #5:

The voices of IDD individuals and their advocates are often quashed because of stereotypes, power imbalances, and lack of representation.

SOLUTION:

Put individuals with IDD and other advocates at the heart of decision making.

INSIGHT: Strong Center advocacy specialist Jeiri Flores has spent a lifetime bumping up against a world that was designed for walkers. When she rolls up to a set of stairs in her wheelchair, it puts that reality into sharp focus. “[In the past,] the person with disability was the issue: maybe I should have found a different way to approach the steps,” she says. “Maybe I should’ve booty scooted up the steps.”

The implications of that barrier are that the systems in place are acceptable, and that an individual must adapt to those systems. But more recently, the spotlight has shifted to the flaws in the systems themselves. “The issue is not me,” Flores says. “[Maybe there just needs to be] a ramp on the side of the steps.”

Through the Strong Center, a federally funded University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities program that helps people with disabilities live their best lives in their chosen communities, Flores shares personal stories like these with many audiences to help advance policy and practice for individuals with IDD. By sharing research, news, and anecdotes, she helps unpack the complexities that people with IDD face in their daily lives.

One overarching goal of the Strong Center’s work is to help give individuals with IDD and their families a stronger sense of agency in efforts related to their support and care.

For example, a Strong Center–supported effort is helping ensure that people with disabilities and their family advocates are fully included and competitively paid as team members to help co-design clinical and research programs at Rochester, says Baker, the family experience coordinator in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. “A mantra of the disability community that we really try to live out in our work is ‘Nothing about us, without us.’”

This story appears in the fall 2024 issue of Rochester Review, the magazine of the University of Rochester.