This woman’s life depended on a determined doctor, a groundbreaking procedure, and an institution built to support the research behind complex medicine.

“We found something.”

A gastroenterologist stood over Jess Delaney-Sloper in the recovery room as she awoke from a colonoscopy. “It most certainly is cancer,” the doctor said.

Delaney-Sloper struggled to make sense of the words. She was a healthy, fit 42-year-old, an avid runner and nurse practitioner. A single bout of rectal bleeding had triggered a small precautionary procedure. Now she lay alone on a hospital bed. It was January 2021, the height of COVID-19, and her husband was waiting in the parking lot to take her home.

Follow-up tests proved the doctor right—only worse: She had stage IV colon cancer. It had spread to her liver. Doctors told her she had two years to live.

The prognosis did not jibe with who Delaney-Sloper knew herself to be. “I thought I was the picture of health,” she says. “I saw my primary care doctor regularly. I worked out every day.” What’s more, she had exhibited none of the other common signs of cancer—weight loss, night sweats, abdominal pain. Just that one minor episode of rectal bleeding.

The doctors encouraged her to make peace with the prognosis. Go live your life, they told her. You don’t want to spend the time you have left in and out of the hospital.

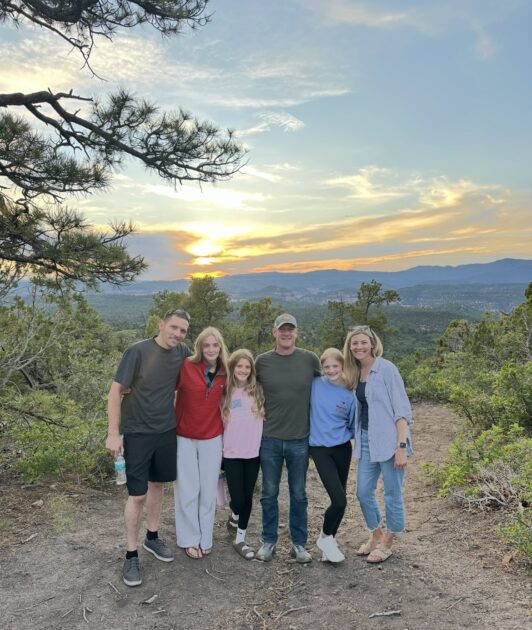

Make peace? Delaney-Sloper had three daughters, ages 7, 9, and 11. She couldn’t accept what amounted to a palliative approach. “I had to be there for them,” she says. “First kisses, puberty, all the things that girls go through—I just couldn’t imagine not being there for that. I couldn’t sit back and accept that diagnosis.”

So she and her husband, Ryan, got to work. They made calls, flew to visit top hospitals, and sought expert opinions across the country in California, New York, and Illinois. Again and again, they heard variations of the same thing: Sorry, there’s nothing we can do.

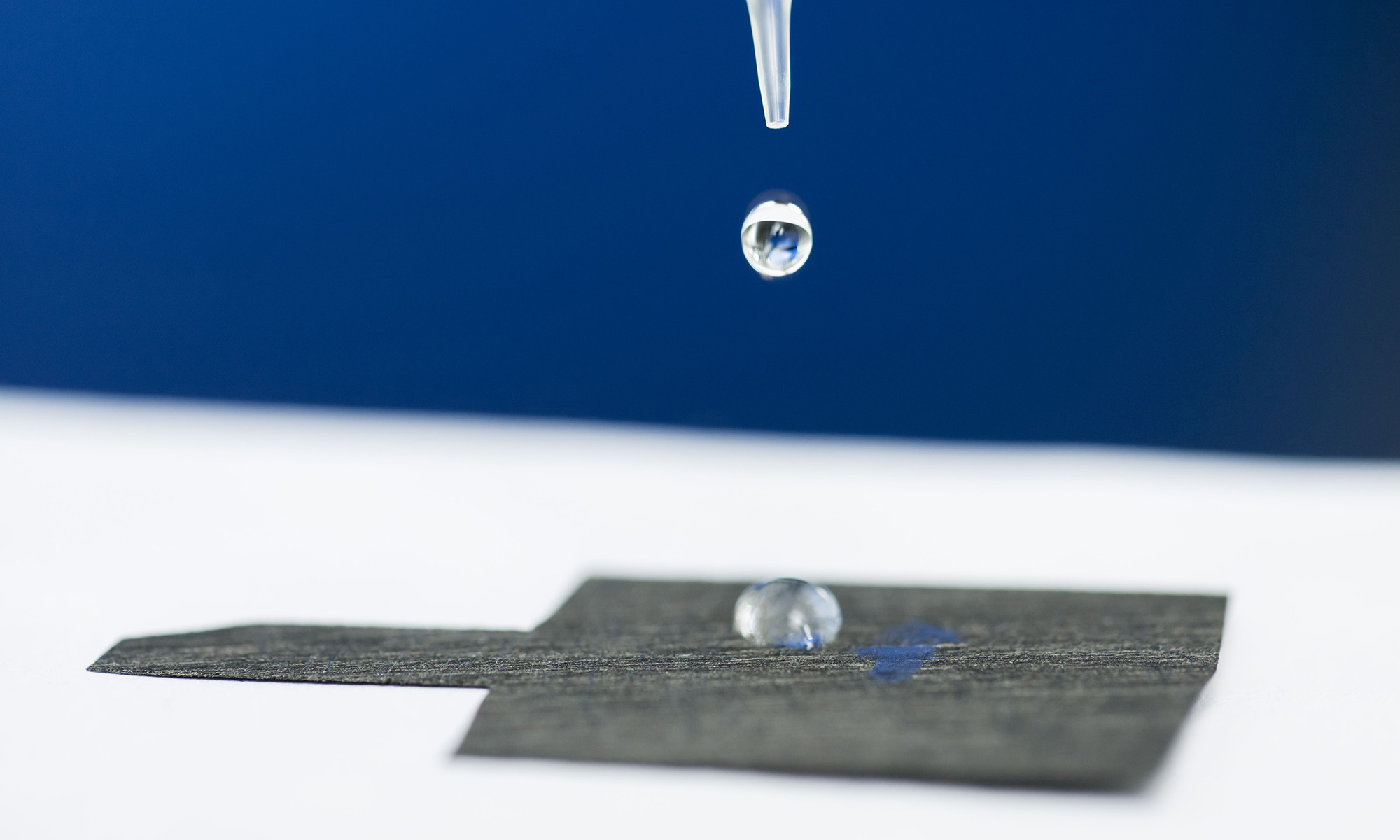

Finally, a doctor they visited in Boston mentioned an option that might just provide a solution. He connected her with Roberto Hernandez-Alejandro, chief of the Transplant Institute at the University of Rochester Medical Center. The regimen was relatively new—and complicated. The procedure entailed transplanting part of the liver of a living donor. Unlike most transplants, a living donation can be scheduled. This allows doctors to perform the transplant at the optimal moment for cancer patients. And because of Delaney-Sloper’s grim prognosis, she likely would not have qualified for one from a deceased donor anyway.

Hernandez had been building a reputation among his peers for groundbreaking procedures on some of the most desperate of patients—particularly those with colon cancer that had metastasized and spread to the liver. He told Delaney-Sloper that she was an excellent candidate for living donor liver transplant surgery. In tandem with colon surgery, the regimen could potentially remove all traces of cancer from her body and eliminate the need for future chemotherapy.

Hernandez did not sugarcoat the many challenges ahead, but he also promised he would help her meet those obstacles with methodical determination. “I always try to have a Plan A, Plan B, and Plan C,” Hernandez says of his approach to every case.

For perhaps the first time since the diagnosis, Delaney-Sloper felt a real sense of possibility. “There had been a lot of doors shut in our faces,” she says. “But Dr. Hernandez opened the door.”

The story of Delaney-Sloper and Hernandez is one of resilience, persistence, and extraordinary medical achievement. It also reflects something deeper: the power of the larger systems that a modern research university can bring to bear to make the extraordinary possible. Hernandez’s vision is leveraged by a team and an institution built to enable bold ideas and complex treatments. But it’s also the most human kind of story—a hybrid of science and deep care.

Seventy volunteers, two livers

How It Works

As part of a multistep treatment approach, living donor liver transplants have the potential to extend lives for some patients with colon cancer and liver metastases.

![]() 1. Diagnosis and evaluation

1. Diagnosis and evaluation

Colon cancer that has spread to the liver is diagnosed.

![]() 2. Cancer control

2. Cancer control

The patient undergoes chemotherapy to reduce or stabilize the cancer.

![]() 3. Colon surgery

3. Colon surgery

The primary colon tumor is surgically removed.

![]() 4. Living donor match

4. Living donor match

A healthy living donor is evaluated for compatibility.

![]() 5. Transplant surgery

5. Transplant surgery

The donor and recipient surgeries happen on the same day: The patient’s diseased liver is removed, and up to 70 percent of a donor’s liver is transplanted.

![]() 6. Recovery

6. Recovery

The donor’s liver regenerates; the transplanted lobe grows to full size; follow-up scans check for cancer recurrence.

(Illustrations by Remie Geoffroi)

Over the course of the next several months, Delaney-Sloper endured a punishing 12-round regimen of chemotherapy to stabilize her cancer and prevent it from spreading further. In August 2021, she traveled to Rochester and spent a week in the hospital for the first surgery: the removal of a portion of her colon and surrounding lymph nodes, performed by colorectal surgeon and division chief Larissa Temple.

The next step was to find a compatible donor, one willing to donate about two-thirds of their liver for Delaney-Sloper’s transplant. She and Ryan gathered dozens of people on a Zoom call to share their story. The couple asked their friends and family to spread the word and to consider getting evaluated as a match. Within 24 hours, 70 people had called in to volunteer for the screening process. “They had to dedicate one nurse just to take calls for me,” she says, clearly moved even four years later by the generosity of their circle.

Her younger brother, Bobby Delaney, a police officer, was the first to call in. He turned out to be a match.

In February 2022, 13 months after her initial diagnosis—and after an additional 10 rounds of chemotherapy—Delaney-Sloper and her brother were in adjacent operating rooms for the lengthy and technically demanding surgical procedures. After ensuring that Delaney-Sloper had no signs of cancer progression, Hernandez removed much of the right lobe of Bobby’s liver, a process that took about six hours.

Then fellow URochester transplant surgeons Koji Tomiyama and Amit Nair removed Delaney-Sloper’s diseased liver. Finally, Tomiyama completed the transplant of Bobby’s liver to Delaney-Sloper.

About 12 hours after they began, the surgeries were complete: Tomiyama and Hernandez debriefed before going home. The procedure, they told Delaney-Sloper later, was textbook perfect.

While Delaney-Sloper spent the first day or so in a sedation-induced haze with her husband and rotating crews of nurses, she does remember the moment her brother walked in, pushing a wheelchair to maintain his balance. She recalls how good he looked—so much better than she had expected after donating 69 percent of his liver. “Seeing him for the first time, I felt pure joy, an overwhelming love for him, and admiration for his bravery. What he had done for me was incredible, and I was relieved that we both got through,” she recalls. “I felt very hopeful for the future.”

The pair was discharged from the hospital eight days later; they spent about a month at a nearby Airbnb so that doctors could monitor their recoveries. Over the course of the coming months, their livers each regrew almost to full size.

Delaney-Sloper continues to adjust to her post-transplant life; she lives with numbness, tingling, and pain from chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in her feet. She continues to have frequent medical appointments, and she will be on immunosuppressants for life. Yet it’s a new—and in some ways more purposeful—kind of normal. “I could be dead right now,” she says matter-of-factly. But she notes that it has been four years since she woke up after that first devastating colonoscopy—two years past the doctors’ initial prognosis. Her most recent scans show no evidence of disease.

Built to go big

Stories about against-the-odds cases like Delaney-Sloper’s often get simplified to highlight a single patient and a heroic doctor. But this kind of storytelling can obscure a reality that is far more layered.

Hernandez does fit the heroic mold. That’s in part a reflection of his relentless work ethic; he has been known to sketch out surgical ideas on cocktail napkins at conferences and to ditch dinners with colleagues to refine those ideas in his hotel room. He jokes that after his own three children, liver cancer is his “fourth child.”

His drive also comes from a deeply personal source: When Hernandez completed his residency at the Mexican Institute of Social Security, his classmates celebrated with friends and family; he attended the recognition ceremony alone. His mother was home receiving chemotherapy for liver cancer, and the rest of his family remained with her as she fought for her life. She died at age 58.

However we wish to portray Hernandez’s heroism, innovations like his demand extensive teamwork and a deep bench of expertise and resources—as he himself is quick to note. “Living donor liver transplantation requires two operating rooms, two groups of anesthesiologists, two groups of nurses, and a donor team,” Hernandez says, ticking off just a partial list of the surgical team. Success involves hepatologists, radiologists, pathologists, pharmacists, infectious disease specialists, nutritionists, psychologists, social workers, nurse practitioners and coordinators, and administrative and support staff.

Their work is urgently, and increasingly, needed. The incidence of colon cancer in people under the age of 55 has nearly doubled over the past decade and continues to increase by 1 percent a year. Medical experts aren’t sure of the reasons; our changing diet, environmental exposures, even microorganisms in our gut might play a role. But Hernandez and his colleagues are focusing on an even more alarming fact: More of these younger patients are diagnosed at advanced stages. An understanding of potential solutions and how to accelerate them is essential.

Hernandez’s pathbreaking liver surgeries began in the early 2010s, when he was working at the London Health Sciences Centre in southwestern Ontario. There he advanced a distinctive two-stage surgical operation to treat liver cancer and metastasis. First presented in 2012 by a German team at a Miami conference, the ALPPS (Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy) procedure offered a promising treatment for patients whose liver cancer was so extensive that it was often considered inoperable. In the first step, surgeons removed tumors from the smaller side of the liver and redirected blood flow to help that side regrow. Then, once the healthy part had regrown, surgeons removed the remaining cancerous section so the patient could survive without liver failure.

The audience of surgeons greeted the Germans’ presentation skeptically, pointing out the significant risk of complications. But Hernandez saw potential for patients who had few other options. He pushed forward with ALPPS, carefully selecting patients with the most promising clinical profiles. The procedure worked once, twice, and eventually some 50 times. While the cancer often ultimately returned, it was extending the lives of patients whose cases had seemed to hold little hope.

The field began to take notice. Soon enough, suitors from around the world were hoping to lure him to their institutions. One of those offering a position was David Linehan, then the chair of the Medical Center’s Department of Surgery.

As Hernandez deliberated over his next move—a move that likely would determine where he spent the rest of his career—he saw major potential at URochester. “I had the opportunity to develop a team,” he says. “And I could be a leader that could have an impact not only in upstate New York but nationally.” To have that kind of influence, he knew he had to have more than a single strong champion. He needed the backing of an institution. With that kind of support, he felt confident he would be able to take his biggest ideas as far as they could go.

He had other options, but he chose URochester. And here he began building clinical and research teams.

The next big swing

Hernandez was eager to recruit fiercely dedicated experts with wide-ranging perspectives, a strategy shaped by his own international training. As a young surgeon he had sought out institutions in Mexico, Canada, and Japan, where he had the chance to study some of the most advanced liver procedures. He wanted to learn from the best, wherever they were. The peripatetic path had additional advantages: It gave him insight into the strengths and shortcomings of different healthcare systems and the influence of cultural norms, lessons he would draw on to navigate complex medical challenges.

For example, Japan’s relatively conservative approach to organ donation from deceased donors had led it to rely more heavily on living donor liver transplantation. It was one reason Hernandez spent several months learning specialized techniques at Kyoto University, where such surgeries took place two or three times a week—far more frequently than at hospitals in North America.

So it was understandable that Hernandez’s first URochester hire would be a Japanese-trained surgeon. Sharing Hernandez’s obsessiveness, Tomiyama was known to practice suturing techniques in his spare time at home. Having worked in Canada and the US, he appreciated both the meticulous approach to surgical techniques that he had learned in Japan and the sense of urgency that moves medicine in America. “The great thing about the US,” Tomiyama says, “is that we try to make things happen as fast as possible.”

Tomiyama would eventually become indispensable for Hernandez’s next big swing: living donor liver transplants for colon cancer patients whose disease had spread to their liver.

Did you know?

The liver is the only organ in humans that regenerates.

A paper by a Norwegian medical team that Hernandez had reviewed for a journal convinced him that such transplants could be part of a cure, despite previous discouraging outcomes that had squelched the practice in the 1990s. With both donor and patient surgeries happening simultaneously, he knew he’d need Tomiyama, a trusted, highly skilled surgical partner, to make the work possible.

To help care for patients before and after a living donor liver transplant, Hernandez has also leaned on the skills of one of his most recent hires, Benyam Addissie. The Ethiopia-born hepatologist is particularly focused on selecting the right patients for this care: “Are they fit enough to undergo liver transplant? Is their cancer too aggressive to be treated safely and adequately with transplant?” He susses out the answers through a range of factors, including a patient’s response to chemotherapy and a series of biomarkers. Addissie’s goal is to prevent a worst-case scenario: a healthy donor who undergoes major surgery for a recipient who dies during or soon after the transplant.

Medical expertise alone will not guarantee a successful transplant. Leaders like Nancy Metzler, executive director of Transplant Services, ensure that the transplant team has the resources, systems, and institutional support for one of the most complex areas in healthcare. While the work of Metzler and her team often gets overlooked, it constitutes an indispensable part of the process. A seemingly trivial misstep—the late signing of a consent form, say—can delay or derail the entire process.

What’s more, ensuring that a patient has a confirmed ride home, or that a nurse is available for a full day to field 70 calls from potential donors, is about more than checking boxes. It’s about creating a larger sense of trust that allows a patient to feel truly cared for. While there are four surgeons in the operating room, Metzler notes, “there are 36 people back here” who have helped get the patient to that point.

The strength of these visible and behind-the-scenes systems leads to extraordinary outcomes. While only a handful of hospitals nationwide have completed even one successful living donor liver transplant for patients with colon cancer that has spread to the liver, Hernandez and his team have completed 26. Data compiled in 2024 of the first 23 patients who have undergone the procedure show that every single one survived at least one year. Ninety-one percent have survived beyond three years. No other institution has come even close.

Talent magnet

Hernandez is clearly competitive, a mindset he frames around leadership and excellence. “Everyone remembers the first person who reached the moon. Neil Armstrong. But who was the second? We want to be the first at Rochester,” he says. “And we want to be the best.” Being a leader requires more than just the technical skills and insight of an individual or even of a highly skilled team like the one Hernandez has strategically helped build. It requires systems and institutional structures that can sustain complexity, support high-stakes care, and turn innovation into standard practice.

One example of this broader, amplifying infrastructure: URochester’s Wilmot Cancer Institute. It was recently named a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center, placing it among the top 4 percent of cancer centers nationwide. The designation acts as a magnet for talent. “It allows us to recruit the best and brightest people from across the country,” says Jonathan Friedberg, director of the institute. “Under Dr. Daniel Mulkerin’s leadership of our cancer service line, Dr. Hernandez’s colleagues, gastrointestinal experts, pathologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and many others demonstrate incredible transdisciplinary collaboration, which is an essential characteristic of an NCI-designated center.”

Among many other functions, the institute helps connect specialists across disciplines to support the development of clinical trials and to streamline patient care. The structure enables deep expertise and cross-field collaboration, which in turn allows treatment of complex cancers.

Wilmot also plays a foundational role in research, where advancing a single discovery often requires the expertise of dozens of scientists. For example, under the guidance of Hernandez, fifth-year surgical resident Matthew Byrne recently authored a research paper about patient selection, insurance approval, and outcomes of living donor liver transplant for those with liver metastases. (The paper includes data from Delaney-Sloper’s procedure.) The 16 authors included 15 from the Medical Center, in areas ranging from surgery to pharmacy. All had links to the Wilmot Cancer Institute.

Beyond the Medical Center, Hernandez can tap into the full depth and breadth of URochester’s research expertise, which goes well beyond traditional boundaries of medicine. That might mean partnering with an engineer interested in robotic surgery or a biologist studying tissue regeneration—insights that could further advance his work.

Hernandez believes that it may be possible to double or even triple URochester’s current rate of these highly specialized procedures, currently about 10 per year. He imagines a future URochester that’s synonymous not just with living donor liver transplants but with other innovative liver surgeries as well.

Still, the goal is not innovation for its own sake. It’s about what that innovation makes possible. For Delaney-Sloper, innovation has meant extra years with her husband and her daughters (now 12, 14, and 16). It has meant more experiences and more milestones. And it has meant a profound connection with her younger brother, who gave her the liver that saved her life.

When she talks about the experience at URochester, she describes it as both “a warm hug” and “a well-oiled machine.” The phrases might seem at odds with each other. Yet together they capture what made her care extraordinary: the kindness and skill of the individuals who provided it, and the precision and power of the system behind them. “I went there for a reason,” she says on a Zoom call a day before she and her family left for a vacation to Zion National Park.

“And I’m still here.”