URochester researchers shed light on the synthetic compounds lurking in everyday life.

PFAS, so-called “forever chemicals,” are as pervasive as they are persistent, raising urgent concerns about our health and environment. At the University of Rochester, researchers across disciplines strive to clarify how PFAS affect immunity, brain development, the economy, and even our daily decisions. Here, three experts share their insight on risks, solutions, and advocacy.

Astrid Müller, assistant professor, Department of Chemical and Sustainability Engineering:

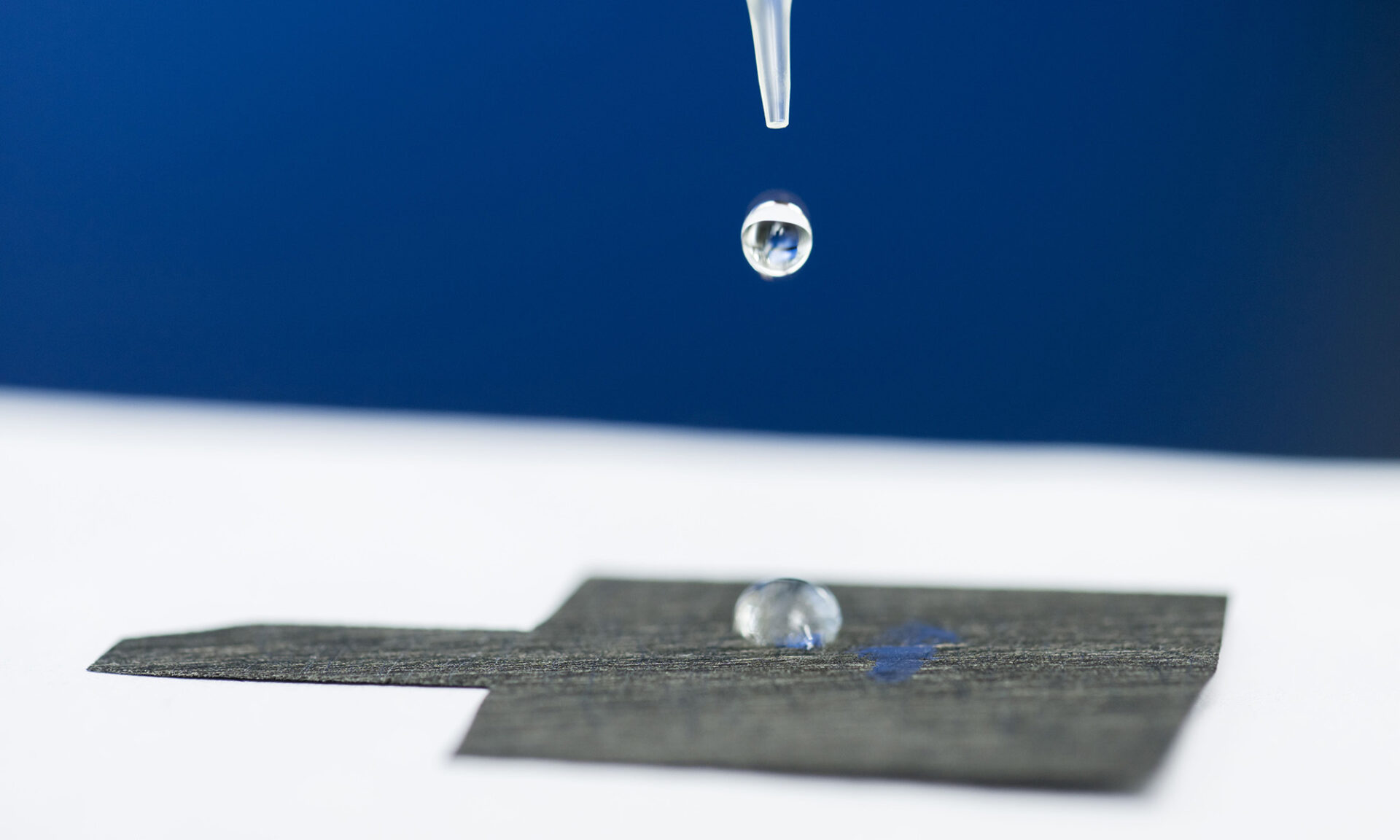

“Many people think PFAS are the devil. Of course they’re harmful—but they’re also everywhere, from laptops and lubricants to catheters, car engines, and cell phones. PFAS compounds have an exceptional resistance to water, oil, heat, grease, and stains thanks to the extreme stability of their carbon-fluorine (C-F) bonds, which makes them highly useful yet difficult to destroy. I envision a more circular PFAS economy in which we use them when they’re necessary, then find safe ways to destroy them. My research focuses on scalable, cost-effective PFAS destruction—driven by renewable energy. Our platform achieves complete defluorination of many PFAS molecules, using industrial nickel-iron alloys instead of costly boron-doped diamond, incineration, or other ‘brute-force’ methods to break the C-F bonds. This technology can be deployed at the source of contamination and sites of discharge: industrial runoff, production sites, or airports that use PFAS-containing ‘firefighting foam.’ This gives us the potential to revolutionize remediation, generate economic opportunities, and improve public health.”

Paige Lawrence, professor of microbiology and immunology; director, NIEHS Environmental Health Sciences Center and the Institute for Human Health and the Environment:

“In studying the environment’s influence on our immune system, I grew interested in why some people become sicker than others after exposure to a virus, for example. Genetics are not enough to explain it; could PFAS exposure play a role? When mice get the flu, they recover; their immune systems learn and remember how to fight it. When they’re exposed to PFAS, though, it dampens that protective immune response. We’re using mice models to hone in on how PFAS may scramble the immune system and its ability to ‘remember’ an invader. I’m also working with [associate professor and co-leader of the research pillar at the Institute for Human Health and the Environment] Kristin Scheible to track T-cell development in newborns. Our research has found that levels of PFAS exposure in pregnancy may weaken the development of specialized T-cells in newborns that fight infections later in life. My advice is to really think about the products you buy and use. Don’t panic, but do take steps to limit PFAS exposure in the ways we know how. For example: Avoid heating food in any kind of plastic container; use glass. Buy pots and pans that do not have a Teflon coating or a label of ‘heat-resistant’ or ‘non-stick.’ Stainless steel is best. And finally, drink plenty of water but use reusable, refillable receptacles. That way, you minimize exposure to the PFAS coating in kitchenware, plastic bottles, and other vessels.”

Marissa Sobolewski, associate professor, Department of Environmental Medicine:

“Most people are exposed to multiple PFAS—and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals—throughout their lives. We know these compounds can enter the brain, even during fetal development. Because they repel oils and water, they can have effects on immune and lipid-dependent brain development. We study the developing fetus to understand the influence of PFAS on brain and behavioral function, as well as on postpartum depression in mothers. My research also examines how PFAS can interfere with hormones, which are critical for both development and mental health. We need to study the ‘curated chemical cocktails’ that mimic real-life exposure to learn how to buffer or mitigate the effects of PFAS. We also need to support the institutions that help regulate both products and the environment, so that the burden shifts away from the individual. As in other areas, our environmental health data can inform public policy with dramatic impact.”

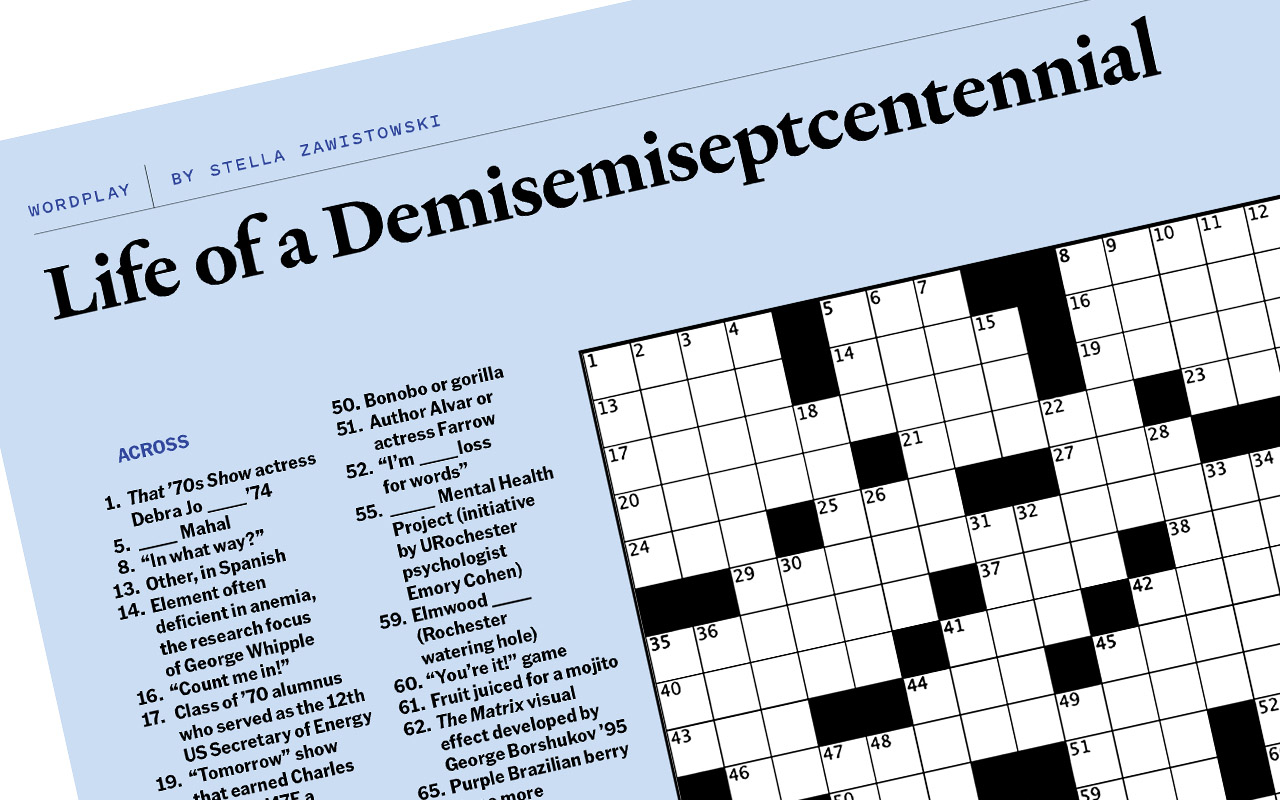

This story appears in the fall 2025 issue of Rochester Review, the magazine of the University of Rochester.