A question for Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian.

Need History?

Do you have a question about University history? Email it to rochrev@rochester.edu. Please put “Ask the Archivist” in the subject line.

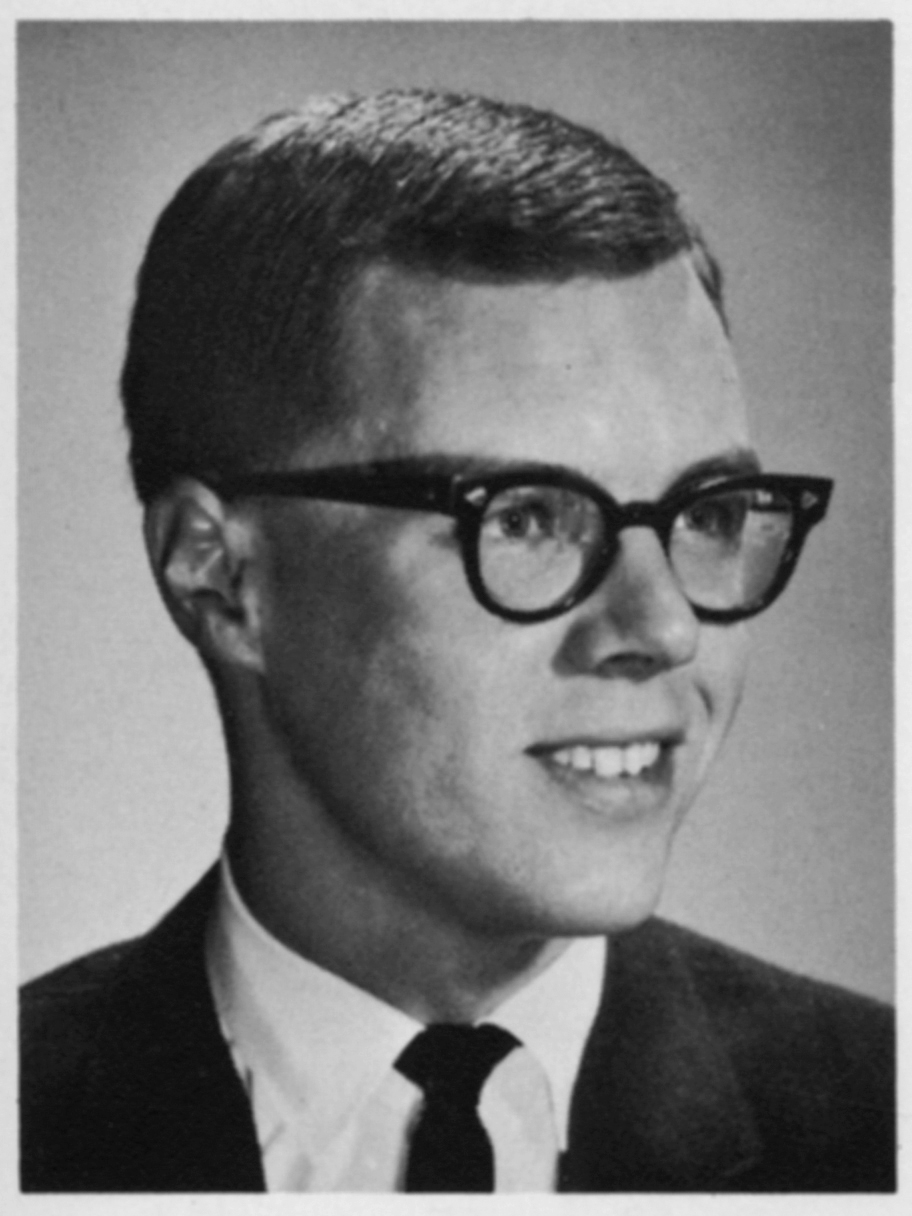

I am interested in learning more about the University’s honor code that I recall that my older brother, Jim Diez ’65, was involved in developing when he was a student. It was a thrill when Jim was accepted to Rochester, the first person in our family to go to college. He was a biology major with a strong interest in nature vs. nurture conversations. He later earned a PhD in bio-behavioral genetics. I didn’t know a lot about his time at the U of R, but a few things stood out—his interest in the honor code, for example, and the fact that he heard John Lewis speak on campus in 1964, which inspired Jim to go to Missouri during spring break to register voters.

—Julie Reynolds

To approach your question in reverse chronological order, your brother had three opportunities to hear John Lewis on the University of Rochester’s River Campus on March 11, 1964. The 24-year-old Lewis first presented a workshop in Todd Union on nonviolence for those students interested in registering voters over spring break. He then spoke at the Alpha Delta Phi house (your brother’s fraternity), and, finally, gave a formal evening speech in what is now Douglass Commons.

Your brother was also a news editor for the Campus Times, a member of Yellow Key (sophomore men’s service group), the Mendicants (junior men’s honor society), the Forensic Society, and the Newman Club. And with classmate Christine Scott ’65, he was cochair of the Students’ Association Committee on Academic Honor Codes.

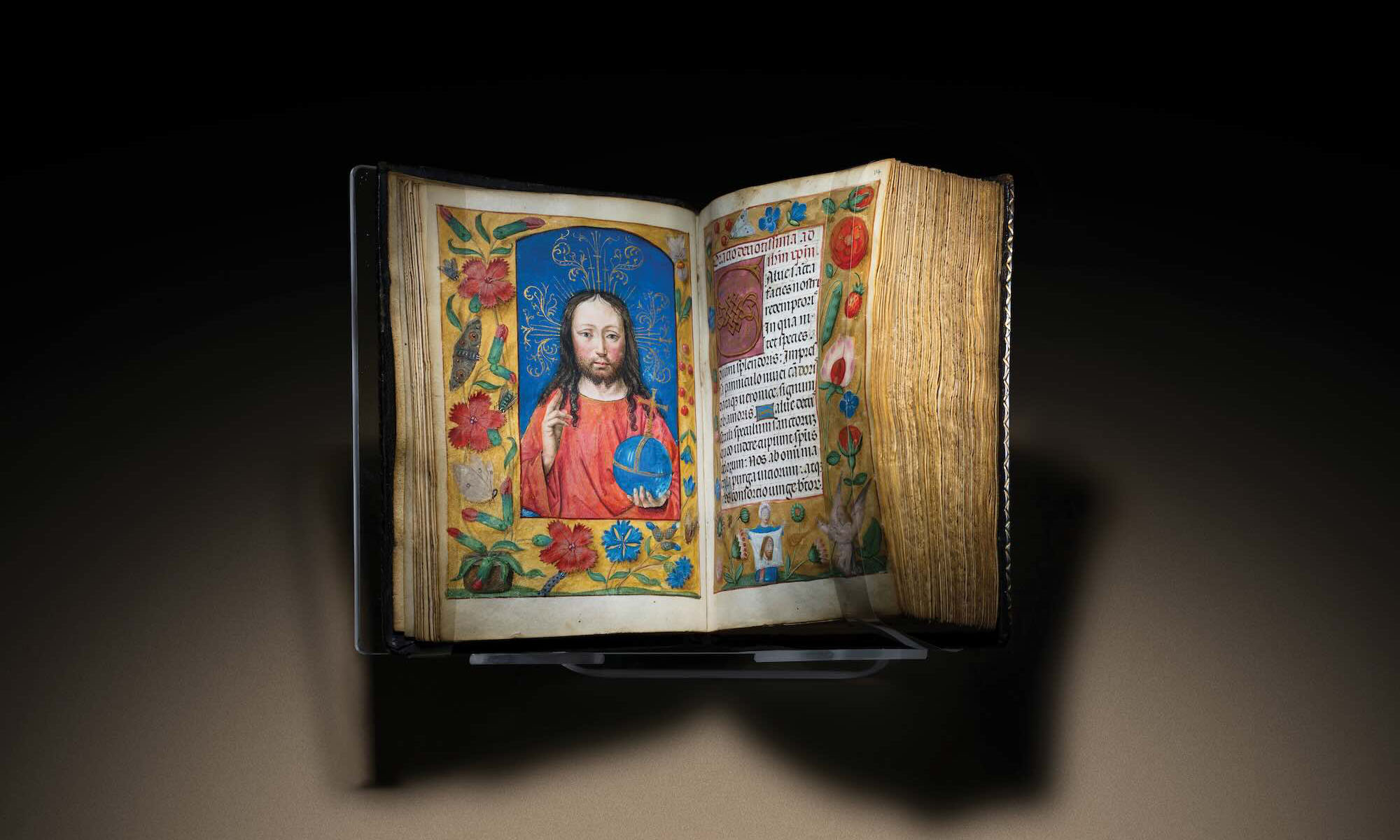

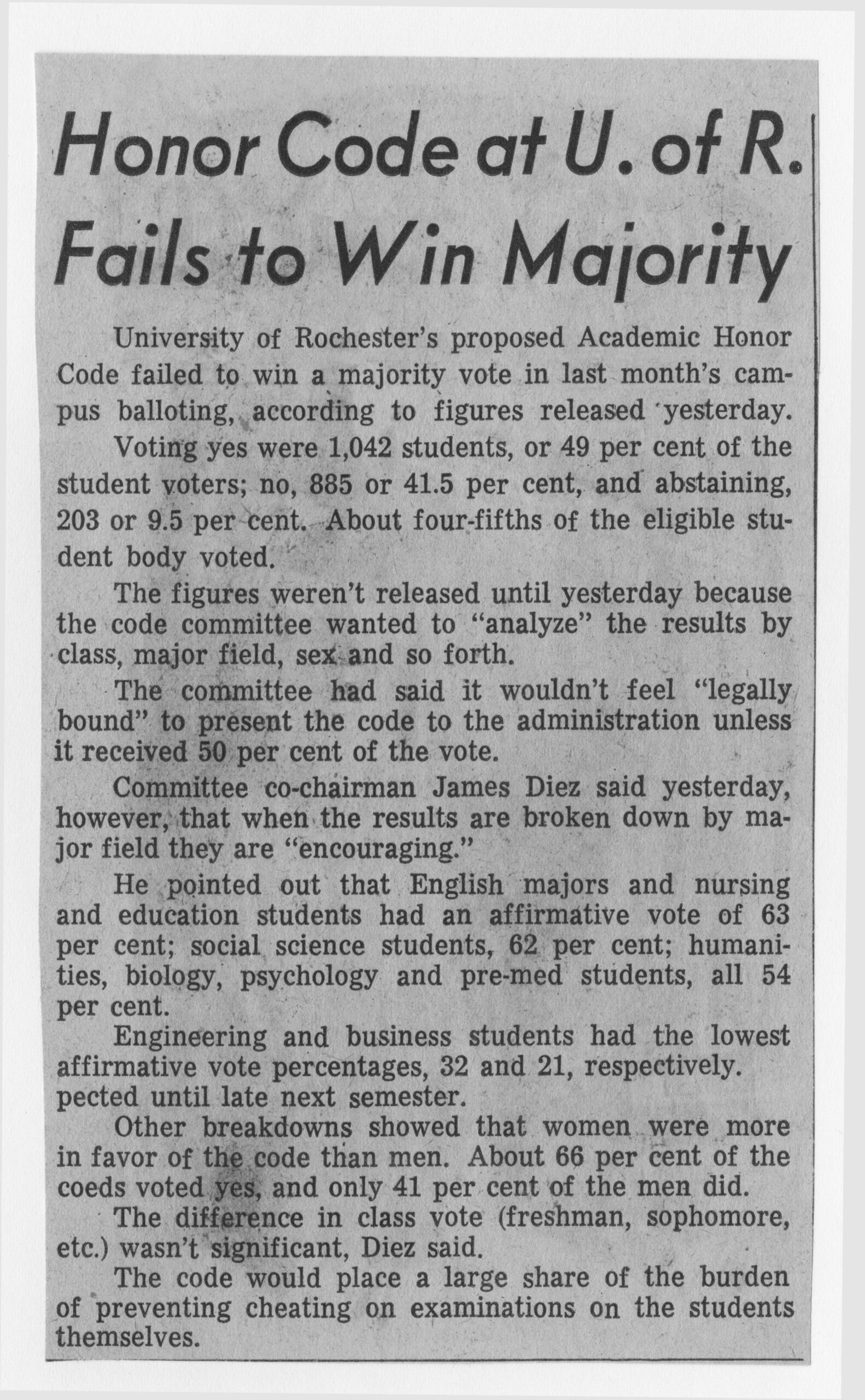

In December 1964, the committee offered a new honor code for their fellow students to vote on. The code, based on the principle that “Each student is responsible for his own actions and is expected to maintain the ethic of the academic community,” also stipulated that “if a student observes another cheating, he is urged to discuss the violation with the offender, and encourage him to discuss the offense with his professor.” If the offender took no action, the student would be expected, but not required, “to report [them] to the Student Honor Board.”

As a percentage of the student population, incidents of cheating in 1964 were probably fewer than in the 19th century. An April 1877 editorial in the Rochester Campus (forerunner of the Campus Times) reported, “It is very evident . . . that the habit of ‘cribbing,’ or cheating in recitations and examinations, is not decreasing in our college . . . . The Faculty tell us that they do not wish to put themselves in an attitude to detect and punish . . . but . . . they are bound in honor to protect the honest men, of whom we are glad to say there are many. . . .”

Joseph Gilmore, professor of English from 1868 to 1908, agreed. His recommendations in an undated proposal to monitor exams may have elicited the April 8, 1882, Campus editorial noting: “It is certainly very amusing to see the students seated in two long lines, facing in, and every man exactly ten feet from each of his neighbors. Then . . . imagine two professors pacing up and down between the lines . . . and you have the Rochester style of examination.”

Voter turnout for the 1964 honor code was done by roll call. Turnout was 80 percent of the student population, but the proposal failed to pass. Although 49 percent were in favor of the honor code, that was just 1 percent shy of the number needed to send it to the faculty for consideration.

The 1964 proposal was not the first, or last, time an honor code was put forth. (Read about honor codes and Academic Honesty regulations through the years.) The earliest honor code was developed in 1910 and passed in 1912. While it effectively ended for the undergraduate men around 1917, it was retained for at least another decade by the College for Women and the Eastman School of Music.

The faculty’s academic honesty regulations preexisted the honor code, although their first appearance in student handbooks may have been in 1929.

The most recent revision of the regulations was approved in May 2023 to address ChatGPT and other AI technologies. It includes a pledge for students to write on their exams or graded work: “I affirm that I will not give or receive any unauthorized help on this exam, and that all work will be my own.”

This installment of “Ask the Archivist” originally appeared in the spring 2024 issue of Rochester Review, the magazine of the University of Rochester.