Eight University of Rochester students are participating in a field school in Ghana this summer, studying historic coastal forts built as early as the 15th century, with particular emphasis on Elmina Castle. Led by Professors Renato Perucchio, Michael Jarvis, and Chris Muir, and teaching assistant William Green, the students are studying the engineering, historical, and cultural aspects of these structures; visiting other points of interest in Ghana – and sharing their experiences in this blog.

June 2, 2017

Accra is only a few degrees latitude above the equator. I’ve never seen the noontime sun quite so directly overhead. We are preparing to conduct a structural study of Elmina, and are practicing using the equipment. As we work, the words of our Ghanaian host, Professor Kodzo Gavua, come to mind. He reminded us to always be mindful of the purpose of our work.

Engineers typically find themselves working in isolation on very detail-oriented projects. However, as we are making our measurements at Elmina, a visitor may become curious and ask us about our project. Anxiety may surround this, and it can convince us that this conversation with our curious new friend is a distraction to our progress.

But progress toward what goal? Our intent is to discover new information, share it, and enrich our understanding. What did this castle look like throughout the ages? How did Europeans and Africans interact with this structure throughout its Portuguese, Dutch, British, and Ghanaian periods? Our study stands a chance of answering some of these questions. This program is specially designed to make us realize how our work is relevant to the passersby and help us develop the skills to explain the importance of what we are doing. So we will begin the conversation. We will explain our purpose. We will show our equipment and what we are doing.

June 4, 2017

Today we had lunch on the Volta River before riding up to Akosombo Dam in torrential rain. At the top, we visited a rest lodge where the view not much more than 20 feet ahead. Two inches of rain fell in 20 minutes and lightning struck less than 100 feet away. Gradually, our gamble paid off. The rain eventually subsided and I could see, faintly at first, the outline of the dam across the horizon. The clouds dispersed and revealed the south end of the third largest manmade lake in the world. We marveled at the half-mile-wide river that the dam held back. Taking time to enjoy the now lighter mist, we walked back to our bus and discovered it had a slowly deflating tire. We had great difficulty fixing it, breaking one tire iron in the process.

We’re two hours from our hotel, haven’t had dinner yet, and are leaving for Elmina at 7:00 a.m. tomorrow on a doughnut spare tire. Hopefully we can make the four-hour drive in time for a tour of the town with Christopher DeCorse, the world’s expert on its archaeology.

This is intense.

June 21, 2017

I am working on my laptop in the Castle Elmina. Groups of young students run along the wooden floors directly above me. Specks of paint and plaster sprinkle from the ceiling onto my face and keyboard as they pass.

A dump truck with a heavy load showed up on the coast this morning. This truck, and the dozens behind it, will install large stones to serve as a barrier against the harsh Atlantic surf. In the long term, this will protect the fishing wharf against storm surges. But this afternoon, the team of students was rushed down to the construction site with cameras to frantically conduct photogrammetry of ruins that may only stand on those shorelines for a few more hours. These are the same stone foundations that Christopher DeCorse taught us about just two weeks ago. While outside, I watched the erasure of an archaeological site we assumed would remain intact for years to come. I turn away from the dump truck, and back to the entrance of the castle, reminded of just how quickly, and without consultation from archaeologists, places like these may be demolished or turned into hotels. Our work generates interest. The interest protects these places. The social integrity and value of the monument is of equal importance to its structural integrity. A well-kept castle is not much harder to demolish than a dilapidated one if the economic forces will it.

June 24, 2017

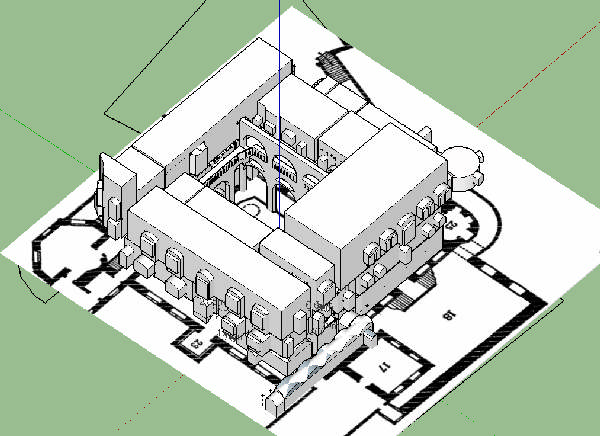

I am sitting at breakfast with a laptop. I had dreaded this moment. In our computer model of the castle, two rooms don’t seem to line up. I know a ceiling can’t be higher than the floor above it, but which measurement is wrong? Did I simply misread the drawing? Can I figure this out before my eggs get cold?

One of the guesthouse staff, Eric, taps on my shoulder and asks what I’m doing. Startled from a focused daze, and turn around to greet him good morning. I show him the CAD model, some of its highlights, and compare it to some older maps we have of the same castle. He says he recognizes the archways of the inner courtyard. Then, Eric says something I don’t expect.

“God bless you for your work.”

This is a humbling moment for me. At Elmina, I sometimes feel confronted with an uncomfortable observation. When we look up at a Dutch vault, stretching our tape measures and talking about the construction, we are standing inside a dungeon. This silent, moldy room once held hundreds of lives stripped of dignity, respect, and humanity. Do we add anything to this gruesome narrative by studying the construction methods of a human trafficking enterprise that sought a 12 percent profit margin? Or are we missing the point?

I look back at Eric. We are not missing the point. He is blessing our attempts to understand, and to safeguard a structure that without continued interest and stewardship, dies, and no longer tells its somber and important story.

Bill Green ’17 of mechanical engineering served as teaching assistant during the field school.