The domestic violence statistics are grim. Every minute across the United States 20 people are physically abused by an intimate partner. That’s more than 10 million women and men every year. One in 15 children will be an eyewitness to such domestic violence abuse. Reason enough for researchers to try to find ways to curb this public health problem.

The domestic violence statistics are grim. Every minute across the United States 20 people are physically abused by an intimate partner. That’s more than 10 million women and men every year. One in 15 children will be an eyewitness to such domestic violence abuse. Reason enough for researchers to try to find ways to curb this public health problem.

An important tool to reduce the recurrence of physical violence and abuse is a court order of protection. Part of that legal process entails the careful documentation of bruising and other injuries. But that’s where it gets tricky: often bruises don’t show up until a few days after the attack. Because time is of the essence in keeping the attacker at bay, some jurisdictions and agencies have been using alternative light source (ALS) lights that reveal bruising that the naked eye cannot (yet) see.

But while existing ALS technology works well for light-skinned victims—it’s a lot less effective for people of color. An interdisciplinary team at the University of Rochester has set out to change that.

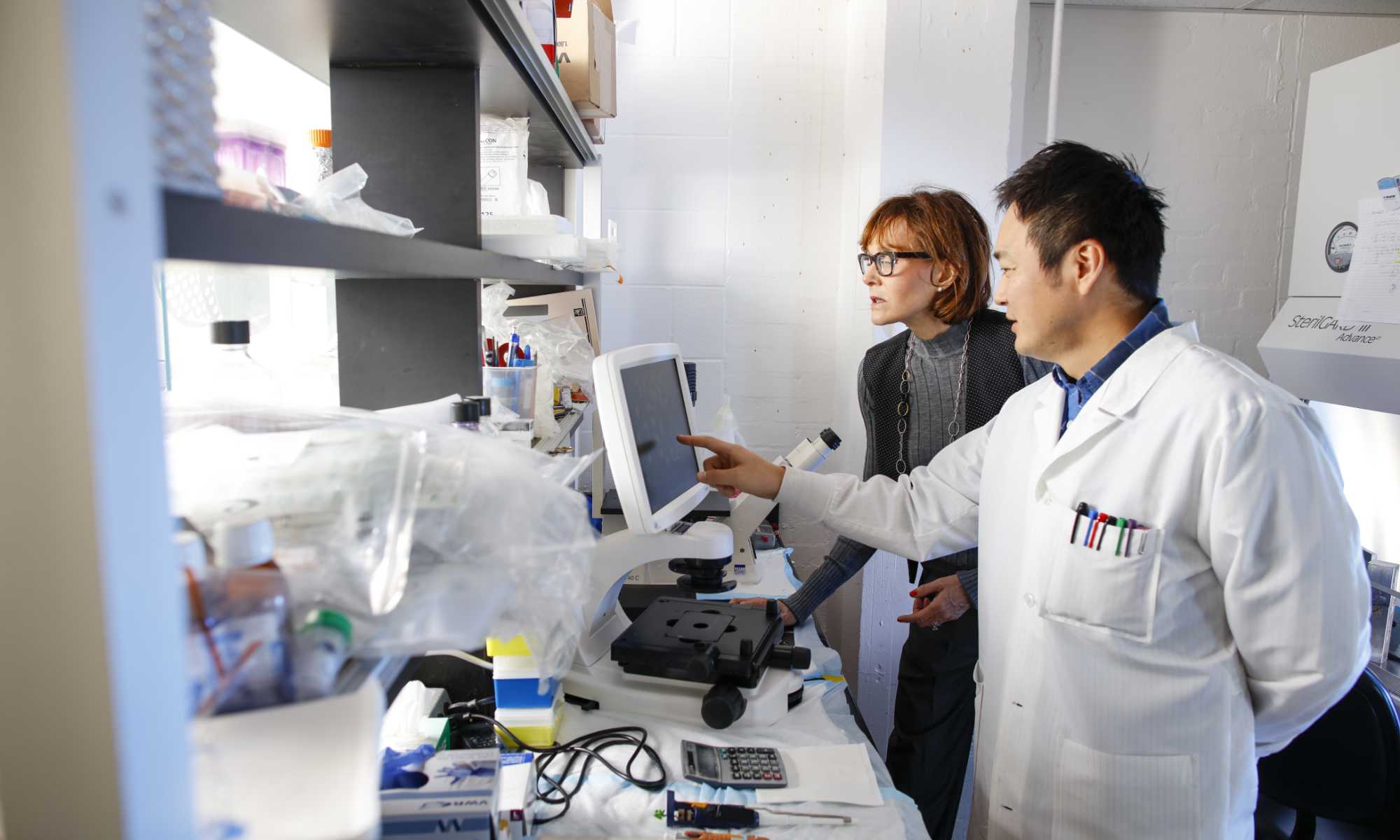

Researchers at the University’s Susan B. Anthony Center and the Institute of Optics have received a $200,000 grant from the School of Medicine and Dentistry’s Scientific Advisory Committee’s (SAC) Incubator for pilot programs. The two-year, community-based study brings together experts across a variety of fields.

Primary investigator Catherine Cerulli, a professor of psychiatry and director of the University’s Susan B. Anthony Center (SBAC), and the Laboratory of Interpersonal Violence and Victimization, heads up the team. Co-primary investigator is Andrew Berger, an associate professor of optics and biomedical engineering. They are joined by co-investigators John Cullen, assistant director of the SBAC, and director of diversity and inclusion for the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at the Medical Center, and James Zavislan, associate dean for education and new initiatives at the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and associate professor of optics, biomedical engineering, and ophthalmology. Together they are working to take skin color out of the equation when it comes to processing these interpersonal domestic violence cases.

“We need to reduce racial disparities for these victims by improving bruising documentation and protection order rates for victims of color,” explains Cerulli.

The study is the result of a multi-year effort between the University and a community partner, Lauren Deutsch, the executive director of the Rochester-based Healthy Baby Network.

“We have conducted preliminary work, which shows that helping professions—such as doctors, nurses, lawyers, or police—would benefit from better techniques to document bruising for all victims of domestic violence—regardless of race, age, and ethnicity,” Cerulli says.

The first phase of the study compares victims’ bruising documentation using traditional digital images against images acquired using ALS lights.

In the second phase the scientists will develop a set of objective tools to identify evidence of abuse or injury independent of skin type. Ultimately, the team’s goal is the development of technology that will improve bruising detection for all.

In the news

- WROC-TV

A new tool coming to the University of Rochester to help victims of domestic violence - WXXI

Study aims to expand technology that uncovers physical signs of abuse

Berger and Zavislan will be working on developing optical methods to show bruises below the thin layer of melanin, the natural pigment that provides color to skin and can mask bruises in dark-skinned people.

“Our task, basically, is to make measurements that target the deeper tissue regions while rejecting the information from the very top where the melanin resides,” says Berger.

Berger likens the to-be developed technology to a pulse oximeter. Like the oximeter, a light-based tool that clips onto a finger or toe to measure heartbeat and blood oxygenation during surgery or intensive care treatment, the new technology will aim to measure blood—as bruises are composed of blood and its chemical breakdown products.

The Rochester researchers are joined by Maryland-based consultant Debra Holbrook, director of forensic nursing at Mercy Health Services in Baltimore. Ultimately, Cerulli hopes the team’s work will prove helpful beyond cases of intimate partner abuse, and be also applied to prevent the recurrence of child and elder abuse.