Dmitry Bykov discusses the late Russian opposition leader’s legacy, his own poisoning, and why Navalny posed a threat to the Russian president.

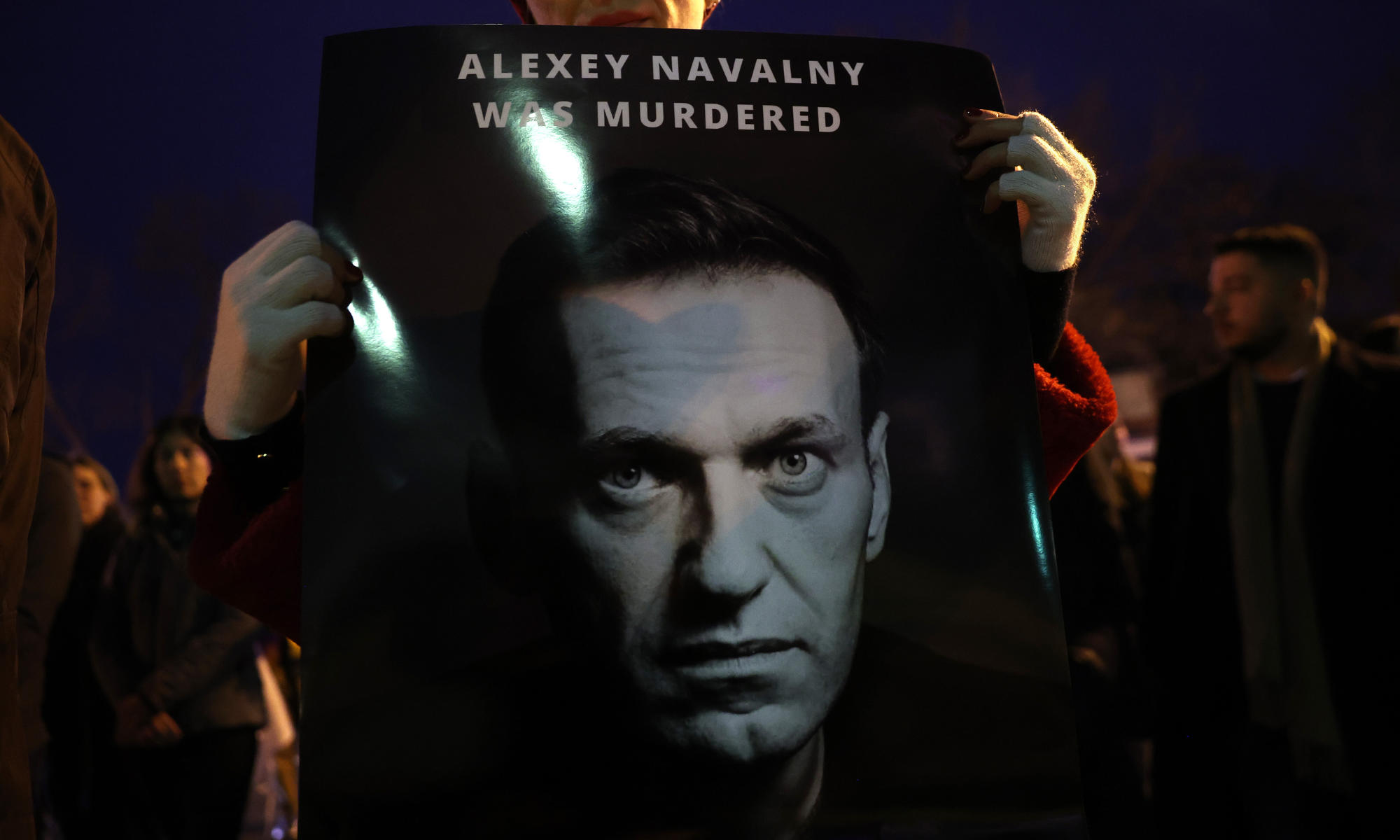

One of Russia’s best-known public intellectuals, Dmitry Bykov, has no doubt. “Calling Alexei’s death ‘suspicious’ is an intolerable euphemism,” says the inaugural Scholar in Exile, a position made possible by the Humanities Center at the University of Rochester. “He was murdered.”

In the aftermath of regime critic Alexei Navalny’s death on February 16 in a remote penal colony in the Russian Arctic, Bykov is convinced that Navalny’s tragic plight will be “turned into a weapon.”

A poet, journalist, satirist, and literary critic, Bykov is no stranger to the power of words and their inherent danger. His satirical poems and sharp political commentaries—often aimed squarely at Russian President Vladimir Putin—did not amuse their subject.

During a domestic flight en route to the western Russian city of Ufa in April 2019, Bykov fell violently ill. Vomiting uncontrollably, he eventually lost consciousness and emerged only five days later from a coma.

A subsequent investigation by the news organization Bellingcat found a striking resemblance between his and Navalny’s poisoning in 2020, likely perpetrated by the same people—an elite Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) chemical-weapons unit.

While Bykov initially remained in Russia after the poison attack, he was banned from teaching at Russian universities and appearing on state-controlled radio and television.

In early 2022, right before Russia invaded Ukraine, the Kremlin declared him a “foreign agent” and many Russian booksellers pulled his works—some 90 total, including novels, biographies, essays, and poetry—from shelves.

Today, as part of the Scholar-in-Exile program through Rochester’s Humanities Center, Bykov teaches courses in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, including Hard Labor, Exile, Prison: The Culture of Incarceration in Russia and Nikolai Gogol and the Creation of Ukrainian Literature. Most recently, he penned a novel about Ukraine’s president Vladimir Zelensky.

Q&A with Dmitry Bykov

An outspoken Kremlin critic, you survived an assassination attempt by the same people who poisoned Alexei Navalny in 2020. What happened to you?

Bykov: While also a critic of the Kremlin, I wouldn’t dare compare myself to Alexei Navalny. As a member of the Opposition Coordination Council, I, too, was on the list of candidates for poisoning. The poisoners followed the list systematically. In general, however, my achievements as a regime critic are quite modest. I have always treated my poisoning incident with irony—as another proof of the weakness and idiocy of the Russian authorities. In a way, it’s the only “bonus” from the Russian state that one can accept these days without feeling ashamed.*

Alexei Navalny’s death in prison looks suspicious. Was he, even in such a remote location, still a real threat to Putin?

Bykov: Alexei died in the Arctic, in the remote village of Kharp, where it was extremely difficult for members of his team, his lawyers, and his relatives to reach him. Without a doubt, he continued to be a danger to Putin—and not just with his letters and investigative disclosures, or through the opposition activities of his supporters, which he continued to coordinate even from prison.

The very example of Alexei’s exceptional steadfastness, courage, nobility of spirit, integrity, and selflessness were crucial for the Russian opposition but dangerous for Putin. After all, any comparison between Navalny and Putin was obviously not flattering to the president. Navalny was never afraid to speak out about the main issues of our time; Putin always avoided answering. Navalny was never afraid of democracy and insisted on fair elections; Putin destroyed the very idea of elections in Russia. Navalny was not afraid of anything, or at least he ignored all threats; Putin is terrified of the future.

When Putin meets with ordinary citizens, he uses members of the secret police to pose as “the people.” Navalny’s very existence, even if he was not allowed to contact his lawyers or write letters to his family, represented a threat to Putin.

But let’s be clear: Calling Alexei’s death “suspicious” is an intolerable euphemism. He was murdered. Whether it was an injection of poison or a shooting in a prison cell, he suffered, at the very minimum, three torturous years of imprisonment. Merely “suspecting” Putin of Navalny’s murder is as absurd as expressing doubts about Putin’s responsibility for starting the war against Ukraine.

Why is Putin so scared of public criticism?

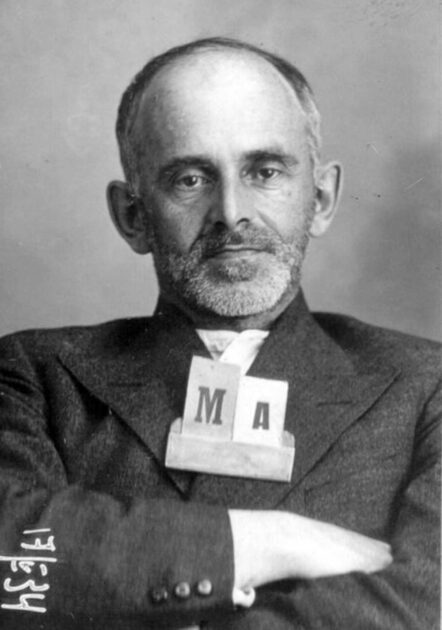

Bykov: [The Russian poet] Osip Mandelstam (1891–1938) was probably right when he told his wife that a dictator’s attitude [then speaking about Stalin] toward literature is always one of fear, that the poet seems to him like a sorcerer, a kind of shaman in alliance with secret occult forces.

The response of any dictatorship to words, especially critical ones, will always be draconian. Putin is afraid of criticism because he’ll never be able to give a reasoned answer. He has never participated in a presidential debate in his life because he has neither convictions, nor fundamental knowledge, nor oratorical abilities. Criticism in general scares only those who are aware of their weaknesses. I think Putin has no illusions about his own abilities—unlike the strength of the Russian army, about which he has too many illusions.

Will Navalny’s death silence or galvanize the Russian opposition?

Bykov: The Russian opposition is alive and active, both in Russia and abroad. It abstains from public actions, marches, and rallies for the same reasons that there were no public protests in Auschwitz. The Russian opposition has already responded quite actively to Navalny’s death, going to specially designated points in Russian cities with flowers and slogans, which immediately led to mass arrests. I think the number of these arrests will grow and cause more and more protests.

As a journalist, you interviewed Navalny on several occasions. What specifically stood out to you?

Bykov: I didn’t know Alexei very well. He was friendly and I interviewed him on at least ten occasions, including during his house arrest. I remember the ankle bracelet he had to wear, which he showed to our photographer. A month later, he cut this bracelet off and went to a mass rally. I will remember his brilliant formula from 2012: “Our task is to create pressure points for them. They don’t know how to deal with challenges. The greater the number of pressure points, the sooner they will topple their own unstable structure.” I think this is true. A dictatorship armed with nuclear weapons cannot be defeated either from the outside or the inside. But it can bring itself down—through its own incompetence, its fear of intellectuals, and the deliberate and persistent degradation of government and the population.

As a critic, writer, and journalist in exile, do you think you’ll be living, working, and writing again one day in Russia?

Bykov: As Carl Jung used to say about his attitude toward religion, “I don’t believe. I know.” I know very few things with certainty, but among those is my firm and undoubted conviction that I’ll be back. I will work as a teacher and writer, although not as a journalist because journalism is less effective than lecturing or poetry. Alexei Navalny had promised me a place in the Russian Ministry of Education. I plan eventually to split my time between Portland, Oregon, and Moscow or St. Petersburg.

Rochester voices

Listen to an episode of WXXI’s Connections with Evan Dawson as University of Rochester experts, including Matthew Lenoe, Randall Stone, and Scholar-in-Exile Dmitry Bykov, discuss the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

What are the prerequisites for you to return safely?

Bykov: I would get on the first direct flight from New York to Moscow. The only condition is that the newspaper Novaya Gazeta and the radio station Echo of Moscow, my former regular places of work that were banned at the beginning of the Ukraine war, would be allowed to start up again. And, of course, there need to be public, legal trials against the military propagandists.

How much longer do you think Putin will last? And what will come afterward?

Bykov: I am neither a prophet nor a fortune teller. I hope Putin will be deposed by his inner circle, crushed by rebellion, or possibly lose his throne as a result of military defeat. Afterward we would, unavoidably, have a short period of turmoil, followed by a period of peaceful and fruitful development, and psychological recovery, in which I hope to participate.

Ultimately, Alexei Navalny’s death will be turned into a weapon. I have no doubt that one day I will walk along a street named after him—not only in America, where there will be such a street, but also in Moscow.

Note

In the aftermath of the attack, Dmitry Bykov was in the intensive care unit of a specialized neurological clinic, the Burdenko Institute in Moscow. The attending physician told him to make the most of his hospital stay, inquiring if he had any other medical issues that needed attention. Bykov mentioned periodic pain in his right knee and promptly received an injection that took care of the problem. “I probably should thank my poisoners for this, but I thank them much more for their professional incompetence,” Bykov says dryly.