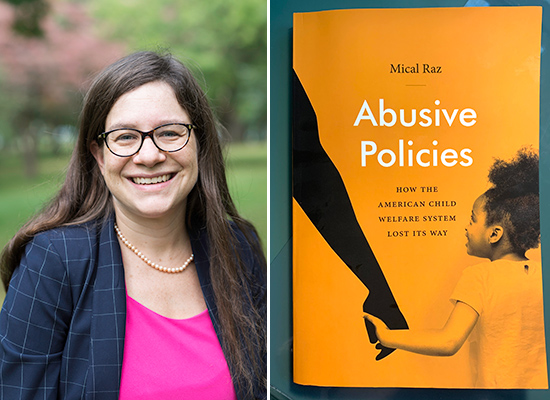

A shift starting in the late 1960s has targeted poor families with unnecessary investigations and child removals at the expense of services, argues Mical Raz.

Black children are removed from their families at much greater rates than any other race or ethnicity in this country. At the same time the sheer number of all child abuse investigations in the US is staggering: experts estimate that by age 18 one out of three children has been the subject of a child protective services investigation. Yet, many of these investigations and removals are unjustified and stem from a misguided policy shift that began in the late 1960s, says University of Rochester health policy historian and physician Mical Raz.

“These numbers are astounding, particularly as the rates of serious physical injury to children are on the decline,” writes Raz in her latest book Abusive Policies: How the American Child Welfare System Lost Its Way (University of North Carolina Press, 2020), which traces the history of child abuse policy in the US over the last half century.

Part of the problem is an overly broad definition of what constitutes child abuse that has become politicized and “weaponized” against vulnerable populations, says Raz, who is the University’s Charles E. and Dale L. Phelps Professor in Public Policy and Health, an associate professor of history, and a physician at the University’s Strong Memorial Hospital.

“Biased viewpoints regarding race, class, and gender played a powerful role shaping perceptions of child abuse,” says Raz. Coupled with overzealous policies and a belief among the public that serious child abuse was widespread and frequent, “these perceptions are often directly at odds with the available data and disproportionately target poor African American families above others.”

This overreporting of alleged child abuse, Raz argues, has caused the child welfare system to get bogged down in unnecessary investigations, seriously undermining its ability to focus on its other roles. Poverty is too often equated with abuse, she says, while at the same time “we’re just having investigations at the expense of providing services.”

Raz is a prolific, award-winning scholar. Her first book, The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery (University of Rochester Press, 2013), won the Pressman-Burroughs Wellcome Career Development Award. Her second, What’s Wrong with the Poor? Race, Psychiatry and the War on Poverty (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), was a 2015 Choice Outstanding Academic Title. Her op-eds are regularly published in the Washington Post’s “Made by History” section.

Q&A with Mical Raz

Why is removing a child who seems at risk a bad thing?

RAZ: We should think about parenting as an affirmative right—that parents have the right to parent their children, that families have a right to be together, and that children have a right to be with their parents. Children should be removed from their families only as a last resort for severe harm. And yet, we know that in the US, about 10 percent of all children, roughly 25,000 annually, who are removed from their homes are returned within 30 days. The problem is not that they are returned too quickly. Rather, what’s the point of taking them in the first place if they can be returned so quickly? Removal unnecessarily creates trauma for children and families and makes them less likely to seek help in other circumstances.

How do race and class bias enter into the perception of child abuse?

RAZ: We know that poor families, particularly poor families of color, are reported to child welfare agencies at higher rates, and child removal happens more often. When a child from a poorer, or Black family is removed—the child is then less likely to come home and stays longer in substitute care—compared to a child from a white family. So, there’s a clear overrepresentation of poor families and families of color.

How did we get here?

RAZ: The evolution of how society views child abuse goes back to an idea from the 1960s that parents who abuse their children are sick and need help. In order to “help” these parents the idea became to better identify them and report more often. Once we started reporting more families, people started reporting more Black and poor families. So, an idea that was designed to provide assistance and social support ended up being co-opted into a way to report and coerce poor families.

What role does poverty play?

RAZ: Since the 1970s federal law has required the reporting not just of abuse but also of neglect, which is a very amorphous category and is too often confused with manifestations of poverty, particularly in a country where we don’t have access to universal health care, or to universal social services. Reporting a family for not having what a child needs to thrive essentially amounts to reporting a family for being poor. Reporting parents, for example, for not pursuing dental care for their child makes little sense because child welfare services are now tied up with chasing up that report, instead of providing the needed services and dealing with the real problem. We know that most reports of neglect are about manifestations of poverty. Often children are removed and placed in foster homes where foster parents get funding from the government. Had that funding instead been given to the original family, they would have been able to provide what their child needs at home. So instead of addressing the underlying poverty, we remove children for other people to raise them.

Isn’t the expansion of mandatory reporting a good thing, given what we’ve learned in recent years about systemic child sexual abuse?

RAZ: We certainly do want people to report cases of child abuse and I regret the many cases that remain unreported. But we know that most reports to child protective services are not about physical or sexual child abuse, but are, in fact, about poverty. And having social workers sort through all of these reported cases is a huge drain on the system: it doesn’t keep families safer, and it doesn’t provide services for families. It actually obscures the problem and makes it harder for social workers to identify the children who are in need of intervention.

What should the system be doing instead of conducting these investigations?

RAZ: It should be providing services to struggling families. In the 1950s and early ’60s before the policy shift, for example, child welfare services would send a homemaker to the home of a recently widowed father, or they would send a caregiver to help a mom who was in the hospital for a gall bladder surgery: they would provide services that would help families who are experiencing difficult situations. What these families needed was help at home, they needed food, they needed childcare. We know families need access to health care, food, and shelter to thrive. What they don’t need is an investigation for neglect.

You write that the definition of child abuse is too general. What needs changing?

RAZ: I think the definitions of child abuse and neglect are far too broad, and yet agents of the state are constantly working to expand them. For instance, in the 1980s and ’90s many states expanded these definitions to include prenatal drug use as a form of child abuse, rather than working to ensure states could offer pregnant mothers treatment for addiction. We should advocate for a narrow definition of child abuse, focusing on cases of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and severe neglect with risk of imminent harm to the child, and find alternative methods to assist families with other struggles that are often related to poverty.

How do you fix to the problem?

RAZ: Given that only a small percentage of reported child abuse cases deal with sexual or severe physical abuse—and those should certainly be addressed swiftly—we should think about the bigger picture in which families are swept into investigations and allegations, where parents later are placed on registries and lose their jobs, or can’t find jobs—for allegations of neglect. If parents lose custody or their parental rights, it’s essentially the destruction of their family. We should instead be thinking of ways to preserve families and offer them services at home. It’s more cost effective and also the right thing to do. When we live in a society in which children may not have access to healthcare, childcare, food, shelter—all these basic things—then if anybody should be charged with neglect it should be the state not the parents.

Read more

Separating children from their families must be last resort

Separating children from their families must be last resort

In an essay published in the American Journal of Public Health, associate professor of history and practicing hospitalist Mical Raz writes that apart from extreme cases of imminent physical harm, “suboptimal families are better for children than removal.”

Will COVID-19 finally spur a revamp of US health care?

Will COVID-19 finally spur a revamp of US health care?

The coronavirus pandemic “has exposed the limits of such an individualistic approach” to health care, writes University health policy historian Mical Raz in the Washington Post.

At-risk families find research-driven services at Mt. Hope Family Center

At-risk families find research-driven services at Mt. Hope Family Center

The Mt. Hope Family Center sits on a two-way street. Its researchers and clinicians have provided evidence-based services to at-risk families, while training the next generation of clinicians and research scientists.