Curt Smith, a senior lecturer in English at the University of Rochester, is a former presidential speechwriter and a noted authority on baseball broadcasting. He gave the keynote address earlier this spring at the annual NINE Baseball Spring Training Conference, which examines baseball history and culture. This guest essay is drawn from Smith’s remarks there. Smith is the host of the “Voices of The Game” series at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. He’s the author of 17 books, including The Presidents and the Pastime: The History of Baseball and the White House (University of Nebraska Press, 2018) and A Talk in the Park: Nine Decades of Baseball Tales from the Broadcast Booth (Potomoc Books, 2011).

After Pearl Harbor, organized baseball doubted if it could or should exist in 1942—or again, ever. Consulted by Major League baseball, the very next day, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt read aloud what became known as “The Green Light Letter,” saying, “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.”

Today’s challenges—from culture to the media, and especially television—imperil the effect of the great work officials, researchers, statisticians, historians, educators, broadcasters, and others are doing for the national pastime. All face the question: How can we help baseball be worthy of the average fan? What lessons from the past can help solve problems today?

A noted broadcaster and I once were asked what baseball meant to us, growing up. Instantly, Bob Costas and I—Baby Boomers both—answered: Everything. It meant everything.

Why was baseball so all-meaning to a Boomer’s era? I begin with the premise that a national pastime must have a national presence. From 1959 to 1964, baseball aired at least four, even five, network television games a week on all three networks—CBS, NBC, and ABC. Not coincidentally, in a 1964 Harris poll, 48 percent of Americans named baseball their favorite sport.

Sadly, a year later baseball slashed its network TV coverage, giving only one network rights to air a weekly “Saturday Game of the Week,” since exclusivity paid more than the several networks had paid separately. Result: by 1968, for the first time, Harris said, “football passed baseball as the favorite sport.” In 1988, baseball gave over almost all its regular-season coverage to ESPN—a cable network then available only in six in 10 homes—and killed NBC’s “Game of the Week.” In 1996, baseball signed a new pact with a new partner, Fox, but that deal still only covers 12 Saturday games a year.

A recent Gallup Poll says that basketball for the first time tops baseball as our second-most-popular sport—football at 37 percent, hoops 13, baseball 9, soccer 7. As bad, says Market Watch, baseball has easily the oldest average TV viewer—57 years. Football’s is 50, basketball’s 42, soccer’s 40. Only 7 percent of baseball’s TV audience is now under 18.

Anyone who likes baseball must be appalled by these facts. So here’s a five-point plan.

First, hire announcers who bring the game to life. Vin Scully, Dizzy Dean, and Ernie Harwell used language to tell stories. Scully decried those who overly use “numbers the way a drunk uses a lamp post—for support, not illumination.”

Second. As noted, revive network TV. It is fine to retain the interested: those fans will seek out cable’s MLB Network or online coverage. But it is far better to grow interest. Get Fox to air whatever it will. Then, renegotiate its contract to add another network weekend afternoon series, begin a show like the 1977–1996 “This Week in Baseball”—and involve CBS Radio, liking baseball far more than incumbent ESPN, with a weekly Saturday game. More networks mean more buzz.

Third, restore TV intimacy. Fenway Park’s home plate camera—your picture window—sits near the field yet above an angled backstop. Contrast such closeness to many parks—Atlanta, San Francisco, Oakland—with a home plate camera so high that the field needs a passport. How baseball-unfriendly is a tube on which little happens—and we can’t see what does?

Fourth, change postseason’s start time. Restore weekend Series games to day coverage. Any Baby Boomer worth their birth certificate knows where they were when Bill Mazeroski homered in the daylight of October 13, 1960. By contrast, last year’s World Series Game Three ended in a kid-free zone of 3:29 a.m. Eastern Time. Yogi Berra said we can observe a lot by watching. The country can’t watch if it’s asleep.

Fifth, don’t make “stop-action” a definition of the sport. 1960’s Game Seven saw 19 runs scored in two hours and 36 minutes. In 1962, the average game took 2 hours and 23 minutes. Last year it took 3:04. In 2018, 10 of the 12 League Championship games took between 3 ½ and 5 ½ hours. Commissioner Rob Manfred says he is “not pleased.” So please people by doing something.

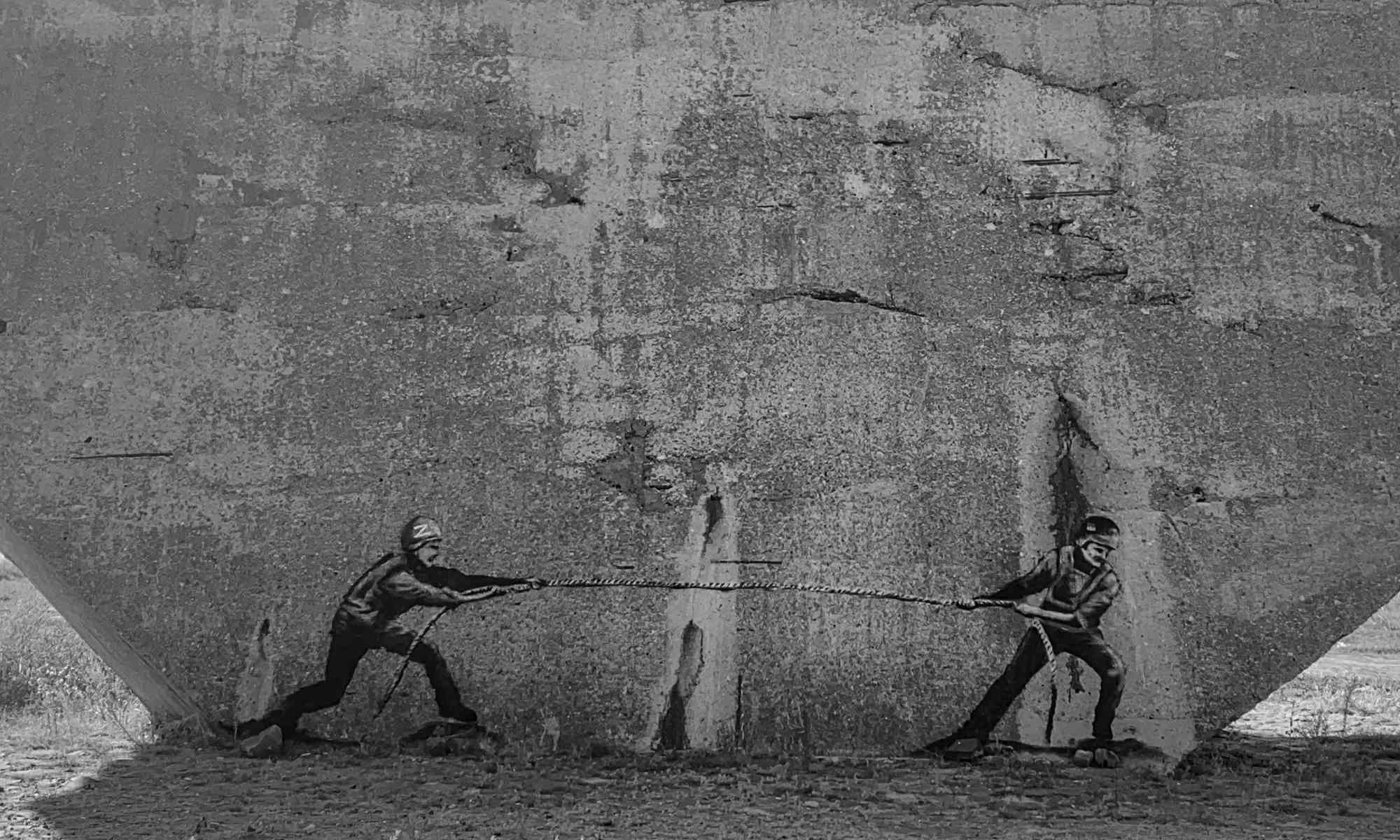

If America could storm Normandy, split the atom, and reach the moon, baseball can uphold the strike zone, keep a batter in the box, and ensure a bases-empty pitch every 20 seconds. As culture turns less patient, pray God, let baseball be less inert.