The concept behind microbial fuel cells, which rely on bacteria to generate an electrical current, is more than a century old. But turning that concept into a usable tool has been a long process. Microbial fuel cells, or MFCs, are more promising today than ever, but before their adoption can become widespread, they need to be both cheaper and more efficient.

Researchers at the University of Rochester have made significant progress toward those ends. In a fuel cell that relies on bacteria found in wastewater, Kara Bren, a professor of chemistry, and Peter Lamberg, a postdoctoral fellow, have developed an electrode using a common household material: paper.

Until now, most electrodes used in wastewater have consisted of metal (which rapidly corrodes) or carbon felt. While the latter is the less expensive alternative, carbon felt is porous and prone to clogging.

Their solution was to replace the carbon felt with paper coated with carbon paste, which is a simple mixture of graphite and mineral oil. The carbon paste-paper electrode is not only cost-effective and easy to prepare; it also outperforms carbon felt.

“The paper electrode has more than twice the current density than the felt model,” says Bren.

Their findings have been published in ACS Energy Letters.

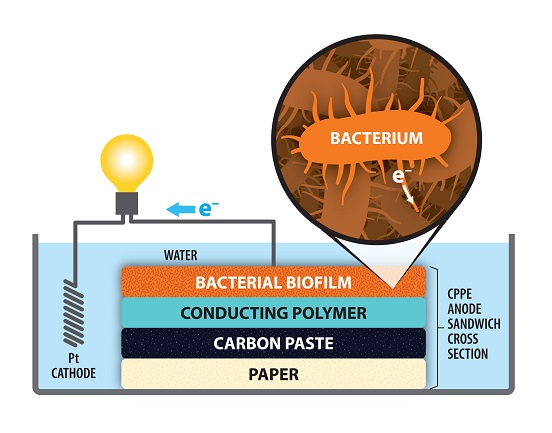

Carbon paste is an essential ingredient due to its role in attracting electrons emitted by the bacteria. The specific bacterium used in Bren’s project was Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, which consumes toxic heavy metal ions in the wastewater and ejects electrons. Those electrons are attracted to the carbon coating on the positive electrode—the anode. From there, they flow to the platinum cathode, which needs electrons to carry out its own electrochemical reactions.

In making their electrode, Bren and Lamberg created a layered sandwich of paper, carbon paste, a conducting polymer, and a film of the bacteria. This easily constructed electrode, surprisingly, had an average output of the circuit of 2.24 A m-2 (amps per unit area), compared to 0.94 A m-2 with the felt anode.

“We’ve come up with an electrode that’s simple, inexpensive, and more efficient,” says Lamberg. “As a result, it will be easy to modify it for further study and applications in the future.”