By partnering with Black actors and artists, the International Theatre Program’s recent productions help give new dimension to marginalized characters.

Like many dramatizations based on real-life events, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible blurs the line between fact and fiction. The award-winning play presents a fictionalized account of colonial America’s Salem witch trials during the late 17th century.

Most historians agree that there are significant differences between the historical record and the actions of the play. Miller, who wrote the play in the 1950s as an allegory about the McCarthy trials occurring during his time, was working with available records. The result is an artistic interpretation, one that includes the small but pivotal role of Tituba, based on a real-life enslaved woman.

Although Miller’s play indicates the character is from Barbados, “Tituba was not African, nor was she from Barbados,” according to Michael Jarvis, a professor of history at the University of Rochester whose expertise includes transnational history spanning the 15th through 19th centuries. Instead, records describe Tituba as being an [Indigenous] Indian. “But since she’s an enslaved person in the documents, Miller implies [her Barbadian origin] in his narrative,” he said during a public panel discussion titled “Finding Tituba’s Voice: Performing BIPOC Characters in White Spaces.”

Fellow panelist Jeffrey McCune Jr., the Frederick Douglass Associate Professor of African American Literature and Culture and the director of the Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American Studies, added that the implication that Tituba is Black “makes her perceptibly an enslaved person. It also makes her perceptibly devalued, part of the lineage of the colonized.”

Understanding Tituba, engaging the community

Jarvis’s and McCune’s insights were made during a discussion about history, authenticity, performance, race, and the performance of race—a discussion spurred by the International Theatre Program’s fall 2022 production of The Crucible.

“The goal of the theater program has been to show serious works of theater that have resonance and also entertain our audiences,” says Nigel Maister, the Russell and Ruth Peck Artistic Director of the International Theatre Program.

Yet as new generations of actors and students take the stage, the theater industry has had to examine its assumptions and biases, particularly with regard to marginalized characters in classic or canonical works. To do so effectively at Rochester, Maister tapped Kat Rina Davis, an award-winning local actor and community advocate, to collaborate and to play the role of Tituba in Rochester’s production. In addition to roles in stage plays, short films, and web series, Davis has played Anna Murray Douglass—an American abolitionist, a member of the Underground Railroad, and the first wife of Frederick Douglass—in Watch Night 1862 by Delores Jackson Radney (Radney, a theater artist and community educator, is also the program manager for MAGconnect at the University’s Memorial Art Gallery).

Having a community member join a campus production—as a performer, an instructor, or both—can help the program as a whole become more inclusive. “When we have the privilege of working with diverse actors in our spaces, we’re always asking about how we do that as responsibly and healthily as possible,” says Sara Penner, a senior lecturer in the program who was the acting and voice coach for the cast of The Crucible.

For her part, Davis agreed to play Tituba as long as she could dig into the character while taking part in the ongoing conversation exploring the character’s role and identity. “I can give [Tituba] a voice,” recalls Davis. “She deserves all that I can give her.”

Maister, Davis, the students, and the other participants collaborated to bring a version of Tituba to the stage who is “very aware of what she’s doing, and it’s not coming from a place of fear,” Maister explains. Tituba’s agency reaches its pinnacle at the end of the first act, when the character confesses to seeing the devil. Participating in both the production and the related panel discussion resonated with Davis in ways that conveyed a clear message, she says: “We don’t only see you, we also hear you.”

But bringing community members into the program also benefits the Rochester undergraduates who learn from the experience and professionalism of area actors.

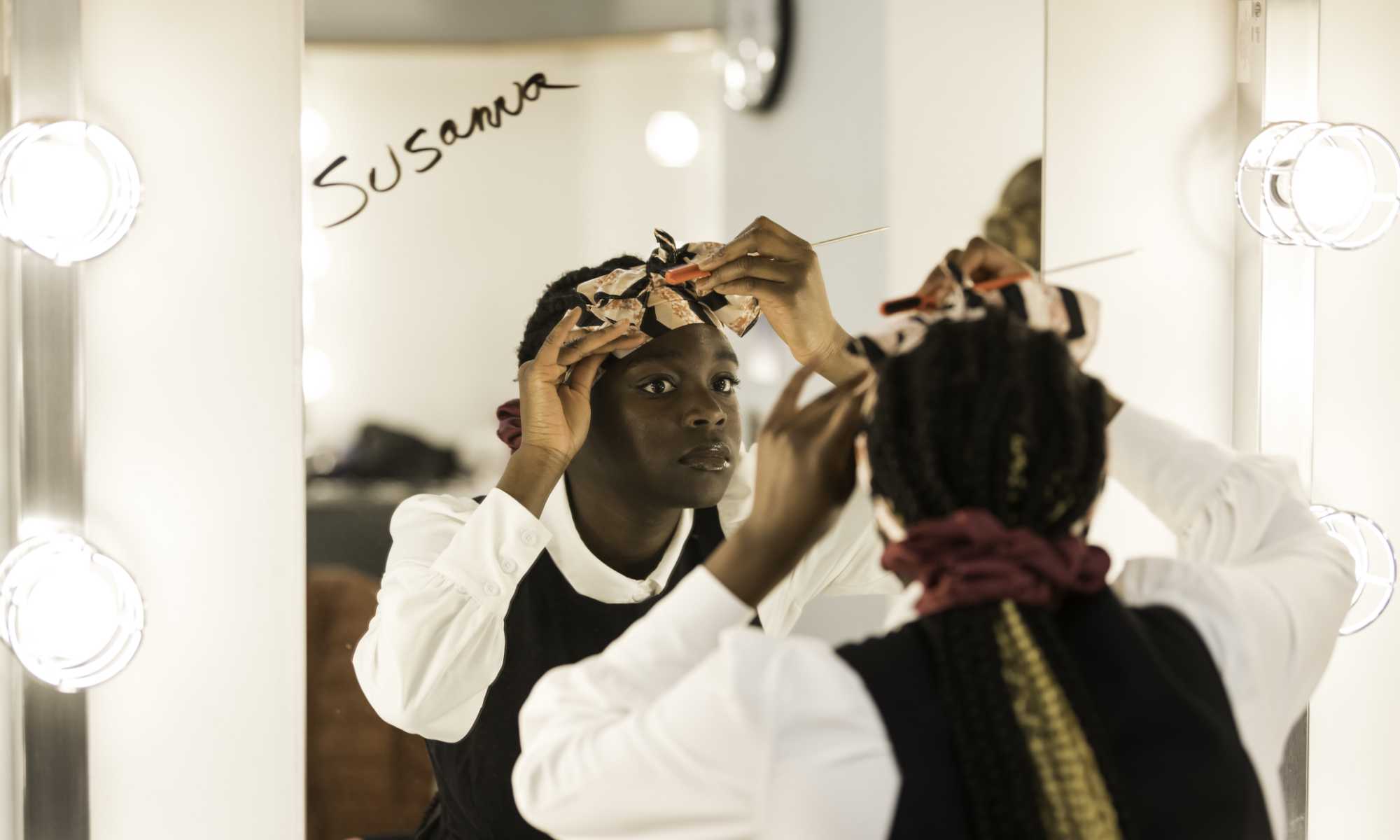

Manita Opoku ’26, who played the role of Susanna Walcott in the production, was impressed by the commitment that community actors like Davis brought to the process. “As students, we’re invested in our studies, classes, and extracurriculars,” says Opoku. “Seeing someone like Kat come in from outside school to act with a busy ongoing life schedule—you could see it was her passion,” Opoku says.

Transforming the theater experience for BIPOC actors and audiences

Centering Tituba during the semester and the production allowed the International Theatre Program not only to bring diverse representation to the stage at the Sloan Performing Arts Center, but also to highlight the challenges faced by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) theater actors.

“You’re asking an actor to display their emotions for your entertainment,” says Esther Winter, an adjunct faculty member in the Rochester theater program and a member of Geva Theatre Center’s Artistic Council. “A real question I ask myself before choosing a play is, ‘What is this theater trying to say in this piece? And what is this piece saying about what they think of people who look like me?’”

Asking such questions—of oneself and of others—is a crucial first step to making theater spaces more inclusive, a step the program intends to continue with its future productions.

“Over the years, we’ve intentionally broadened the reach of the program into the Rochester community—and we’re now trying to broaden that reach to communities of color specifically,” Maister says.

For example, every four years or so, the International Theatre Program commissions, produces, and premieres a brand-new play from an upcoming playwright. The New Voices Initiative supports early-career playwrights while educating Rochester students about the artistic process. Before the The Crucible, the theater program presented Fellowship, a play by Asian American playwright Sam Chanse. Contemplating ideas of privilege and identity, the work explores what happens when college-age activists are brought together as part of an internship for a respected grassroots social justice organization. The world premiere of the play, which was held in fall 2022 at the University’s Sloan Performing Arts Center, featured an acting ensemble composed predominantly of performers of color.

And for its next production, according to Maister, the International Theatre Program hopes to show a different paradigm of Black theatricality on the stage: The African Company Presents Richard III by Carlyle Brown. The work, which is based on the story of the first African American theater company, brings Davis back to campus as the production’s acting coach, while welcoming Jamaican performer, producer, educator, and activist Vernice Miller as guest director.

Read more

Can arts integration deepen students’ understanding?

Can arts integration deepen students’ understanding?

A partnership between City of Rochester schools and the Memorial Art Gallery leads to innovation in arts education and furthers the museum’s mission to serve the Greater Rochester community.

Sam Chanse play premieres at Sloan Performing Arts Center

Sam Chanse play premieres at Sloan Performing Arts Center

Fellowship is the latest production commissioned as part of the International Theatre Program’s New Voice Initiative supporting early-career playwrights

Is gospel music losing its Black roots?

Is gospel music losing its Black roots?

Musicologist Cory Hunter identifies a notable contemporary shift in the century-old musical form.