In 2021, the University’s prison education program started courses at Attica, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the prison uprising.

Editor’s note: This story was originally published on September 8, 2021. It has been updated and republished to reflect renewed funding for the Rochester Education Justice Initiative from the Mellon Foundation.

Mellon Foundation renews support for Rochester Education Justice Initiative

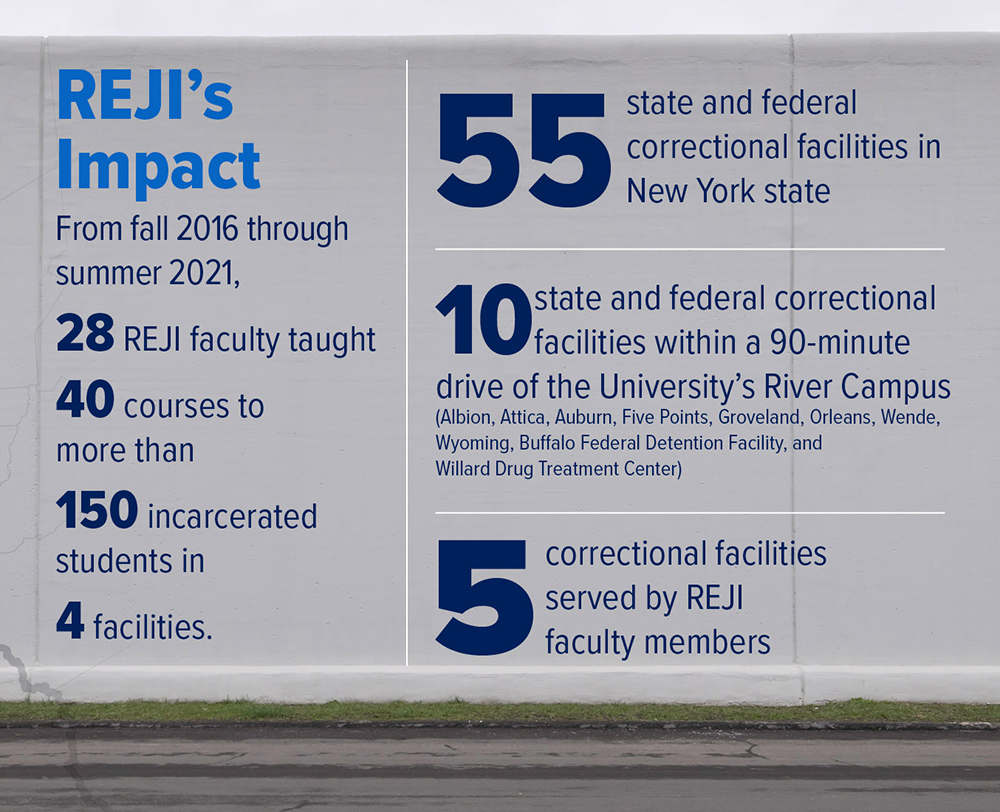

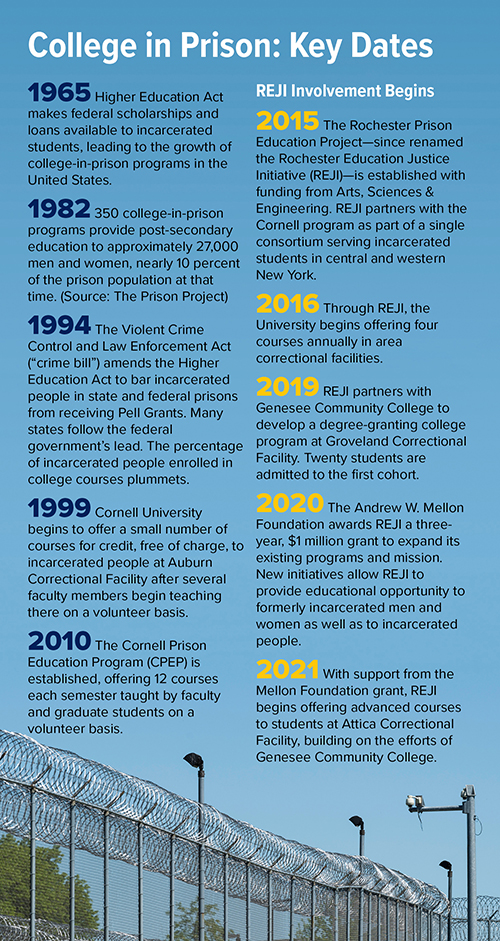

In 2022, the Mellon Foundation renewed its support for the Rochester Education Justice Initiative (REJI) with an additional three-year, $1 million grant. The foundation awarded the University-affiliated prison education initiative a similar grant in 2020 and has been its principal funder. The second Mellon grant will enable REJI to continue its existing associate degree-granting programs at Attica and Groveland Correctional Facilities, expand operations to a third prison, Wyoming Correctional Facility, and realize its long-term goal of offering a bachelor’s degree to incarcerated students at Attica Correctional Facility.

“We’re extraordinarily grateful to the Mellon Foundation for its transformative support.

With this support, we are working with allies across the University to launch a BA program at Attica,” says Joshua Dubler, REJI’s faculty director and an associate professor in the Department of Religion and Classics. “Offering a bachelor’s degree to a highly motivated, qualified, and committed group of students will place the University of Rochester among the vanguard of higher education in prison.”

September 2021 marks 50 years since the uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility, about an hour’s drive from Rochester, New York. On September 9, 1971, prisoners gained effective control of the facility, took 42 hostages from among its staff members, and presented the state’s commissioner of corrections with a list of demands. On September 13, they were still negotiating over amnesty for participants in the uprising when, upon the orders of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, more than 400 state troopers descended on the facility, spreading tear gas, followed by gunfire that killed 29 incarcerated men and 9 correctional officers and civilian staff.

The tragedy gained Attica notoriety from which it has never fully recovered. Open wounds endure in Rochester, the home or near to the home where several survivors live, as well as family members of both survivors and victims.

Amid the dark shadow cast by the event, the University of Rochester’s Rochester Education Justice Initiative, or REJI, has expanded its program to Attica. Fifty years after the uprising, it’s the start of a new semester in which 26 incarcerated students at Attica are taking one or more of six college classes offered through REJI, setting them on a course that REJI hopes will eventually enable them to earn bachelor’s degrees.

Since 2011, incarcerated men at Attica with a GED or high school diploma have been able to work toward an associate degree by taking courses offered there by SUNY Genesee Community College. This year marks the start of a new partnership between GCC and the University of Rochester. The partnership is led by REJI and modeled after a similar one with GCC started at the Groveland Correctional Facility in Livingston County in 2019.

Eitan Freedenberg ’20 (PhD), assistant director of programming for REJI, believes that Attica is well suited for a bachelor’s degree program.

“We’re working to recruit associate degree holders there, whether they earned their degree through GCC or another institution, who would be natural candidates for continuing their higher education,” says Freedenberg, who began teaching incarcerated students at Five Points Correctional Facility in Romulus, New York, in 2017.

Participants in higher education at Attica may well have a better chance to build new lives for themselves upon release. The barriers to reentry to society remain steep, and REJI has expanded its role from serving incarcerated students to helping formerly incarcerated people overcome those barriers. But studies consistently show that education helps reduce recidivism. A 2018 meta-analysis of 37 years of studies concluded that individuals who had participated in an education program of any kind while incarcerated had 28-percent lower odds of recidivating than those who did not.

Leading prison education in western New York

If Attica is uniquely suited as a site for a bachelor’s degree program, so too is the University of Rochester uniquely suited to lead it. REJI is among some 200 or so college-in-prison programs in the nation and one of several such programs in New York state. Founded in 2015 by associate professor of religion Joshua Dubler, the initiative got started with seed funding from Arts, Sciences & Engineering.

Dubler’s model for REJI was the Cornell Prison Education Program, or CPEP. When he arrived at Rochester in 2012, he had just completed the manuscript for his first book, Down in the Chapel: Religious Life in an American Prison (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), based on fieldwork at the maximum-security Graterford State Correctional Facility near Philadelphia. As he wrote more recently in his 2016 book Break Every Yoke: Religion, Justice, and the Abolition of Prisons (Oxford University Press, coauthored with Vincent Lloyd), at Graterford “prison teaching became a vocation.” From that time on, “I promised my incarcerated friends that going forward I would strive to earn the trust that they had placed in me.”

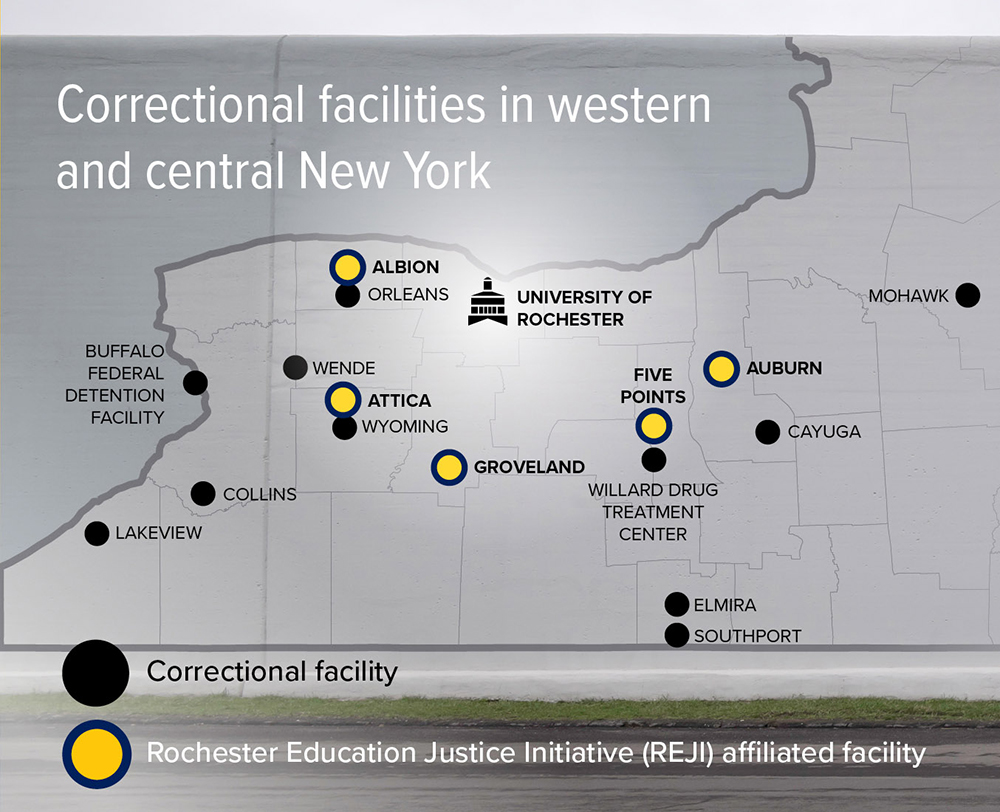

Dubler began teaching with CPEP as an affiliated faculty member—just as today faculty from nearby institutions including GCC and Nazareth College affiliate with REJI. It became clear that what Cornell was for central New York, the University of Rochester could be for western New York: an institutional leader and hub providing college-in-prison opportunities in an area dense with prisons.

A network of faculty and graduate student instructors began to grow around the idea. It included associate professor of anthropology Kristin Doughty and associate professor of philosophy Alison Peterman, who continue both to teach with the program and to serve as advisors to other REJI faculty members; and Ed Wiltse, a professor of English at Nazareth College who had founded the Jail Project at Nazareth in the early 2000s, and who is now REJI’s admissions coordinator.

Another early collaborator was Precious Bedell, who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees while incarcerated and, after her release, founded a nonprofit, Turning Points Resource Center, to provide services and support to incarcerated people and their family members. Bedell, who is now REJI’s assistant director of community outreach, has expanded the nonprofit’s mission to serve formerly incarcerated people who face many barriers in reentering fully into society. Each year, she coteaches with Dubler a lecture course called Incarceration Nation about the origins of mass incarceration in the United States.

REJI attracted community support to supplement seed funding from the University. Initial support came from the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation and later, from the Max and Marian Farash Charitable Foundation. And in 2020, REJI won a three-year, $1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which has enabled the group to expand its work in multiple ways, including in its partnership with GCC at Attica.

REJI faculty have taught at the Albion, Auburn, Five Points, and Groveland correctional facilities. With the expansion to Attica, REJI becomes the western New York hub of prison education that its founders envisioned. Freedenberg, who handles the complicated logistics of operating a college-in-prison program, sees the expansion as a significant milestone for the University.

Programs at downstate universities, such as Columbia and NYU, or in the Hudson Valley region, home to the consortium Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison, serve prisons large and small that are relatively near their campuses. “Attica is right in Rochester’s backyard,” Freedenberg says. “This is our region, our community, our responsibility as a university.”

The politics of prison education

It’s a stipulation of the partnership between GCC and Rochester that REJI has final say over admissions to the Attica program. But the applicants tend to be a self-selected group, and Freedenberg emphasizes that within certain parameters, admissions are “as open as possible.”

Those parameters include some practical considerations. For example, REJI looks at applicants’ release dates to make sure that they can complete at least one semester. Successful applicants also can’t have any disciplinary actions on their records. Beyond those considerations, the selection process is largely based on written communication skills. “We do a lot of qualitative assessment of college readiness based on prospective students’ application essays,” Freedenberg says.

One potential criterium that is not considered is the nature of the offense that landed the applicant in prison in the first place. That’s consistent with the philosophy that unites REJI’s faculty and staff. Incarcerated people are disproportionately poor and, Dubler says, “I’m really allergic to distinguishing between the deserving poor and the undeserving poor.”

“We’re a pretty violent culture,” he explains, and one with “a habit of disposing of people. And prisons are one of the places we dispose of people.”

Nearly every person you ask who has taught incarcerated people says they have been profoundly moved by the experience. Marianne Kupin-Lisbin, REJI’s program coordinator and a doctoral candidate in history at Rochester, says of her past teaching at Five Points, “to this day, I don’t think I’ve had a better pedagogical experience.” The students are hungry for an opportunity they have not had, giving the professor, and each other, their full attention. Freedenberg—who also notes that the students have no access to the internet—calls the incarcerated students he has taught “amazing. They are a really unique group of students who are committed to being a community of learners together. And they’re committed to the well-being of this program.”

Those involved in prison education know not to take the well-being of the programs for granted, given the dramatic shifts in support for them over the past several decades.

College-in-prison programs burgeoned following passage of the Higher Education Act in 1965. The act broadly expanded access to higher education through the creation of federal student loans, work-study programs, and most importantly, Pell grants—need-based awards available to students pursuing higher education, including students who were incarcerated. Fueled by these grants, by the early 1980s there were well over 300 college-in-prison programs run by colleges and universities across the country.

Among the incarcerated students benefitting from Pell grants was Bedell. She had started community college in Syracuse when she was arrested and sentenced to serve at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women, in Westchester County. She completed a bachelor’s degree as well as a master’s degree in developmental psychology from Norwich University while incarcerated.

“The administrators at Bedford Hills and at the Department of Corrections were just so supportive of people doing college programs, and we had graduations and certificates and vocational programs,” she recalls.

It’s a more difficult environment for potential students in prisons today.

In the immediate aftermath of the Attica uprising, a progressive spirit took hold leading to public discourse about the need to make prisons more humane, and in some quarters, to ask what compelled Americans to think prison was an appropriate or effective form of punishment in the first place. But coinciding with those impulses were others that headed in the opposite direction, responding to the uprising with a zeal for a tougher approach to crimes and to those convicted of them. The latter approach proved far more popular politically.

Starting about 1974, incarceration rates ballooned. At the time of the Attica uprising, there were roughly 200,000 people in the United States in state and federal prisons, or 95 per 100,000 people in the US population, according to data from the Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, which has been compiled by the Prison Policy Initiative. By 1977, it was 125 people per 100,000; by 1982, 170 people.

In 1994, Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, commonly known as the crime bill. That year, there were more than 1.5 million people in state and federal prisons, amounting to just over 500 per 100,000 people—more than five times the rate in 1971. Among the provisions of the bill that ran more than 350 pages was the elimination of Pell grants for incarcerated people. Many states, including New York, followed suit, making incarcerated people ineligible for state-based assistance.

Pell grant eligibility was restored late last year in a provision of the stimulus bill, which was included following the success of the Second Chance Pell, a Department of Education pilot program initiated in 2016. But the bill will not be fully implemented, according to the DOE, until the 2024–25 academic year. And in New York, incarcerated students remain ineligible for the Tuition Assistance Program (TAP).

Investing in ‘human flourishing’

“That was a very sad era,” Bedell recalls, of the aftermath of the crime bill. With few incarcerated students able to afford courses, demand fell, and colleges and universities folded their programs.

But some advocates of college-in-prison, including individual higher education faculty members, staff at correctional facilities, and incarcerated men and women, began collaborating to try to find means to deliver courses anyway. In the mid-1990s, Bedell says, some faculty members at a few downstate colleges began collaborating with incarcerated women at Bedford Hills and other facilities to offer occasional courses. Cornell’s CPEP program had similar origins. In recent years, foundations such as Mellon have provided substantial backing, helping generate something of a renaissance of college-in-prison programs. And universities, including Rochester, have offered resources as well.

“In terms of offering credits at no cost, supporting faculty with on-load teaching, and supporting the recruitment of formerly incarcerated students, the University is stepping up,” Dubler says.

Bedell credits both the Mellon Foundation and the University for enabling her to recruit formerly incarcerated men and women to become students at local institutions, including Rochester, where they study as Justice Scholars. “I’m excited about the possibility of continuing to build a cohort,” she says of the scholarship program that has so far enabled two formerly incarcerated students to pursue degrees at Rochester.

In addition to staff at Bedford Hills, it was university faculty members who enabled Bedell to take her own desire to turn her life around and make it a reality. Geraldine Downey, a professor of psychology at Columbia, mentored her through a master’s thesis on resilience in women, providing her with research opportunities. That led Bedell to her career at the University, where for eight years she worked community health worker and a human subjects research coordinator in the Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry. In 2015 the Medical Center’s Center for Community Health and Prevention awarded her the David Satcher Award for Community Health Improvement and in 2016, she was awarded a Staff Community Service Award by her Medical Center colleagues for her work with Turning Points Resource Center.

“We’re using incarceration as a way to solve our social problems,” Bedell says. “The War on Drugs is also a war on the poor, particularly on women, who are the fastest growing segment in the prison population in the United States.”

Dubler points to the correlation, over the past several decades, between public disinvestment in education and social supports and public investment in prisons. What if, he asks, we had been “investing instead in a set of institutions that could enable human flourishing?”

Universities are such institutions, and they are, as Dubler says of Rochester, stepping up. But decades of mass incarceration makes their task sobering.

When it comes to Attica in particular, Dubler asks: “How might Rochester’s offering of college courses there adequately respond to the legacy of the tragedy? It’s a humbling question, and one that we are hoping to figure out in collaboration with our institutional partners and our students.”