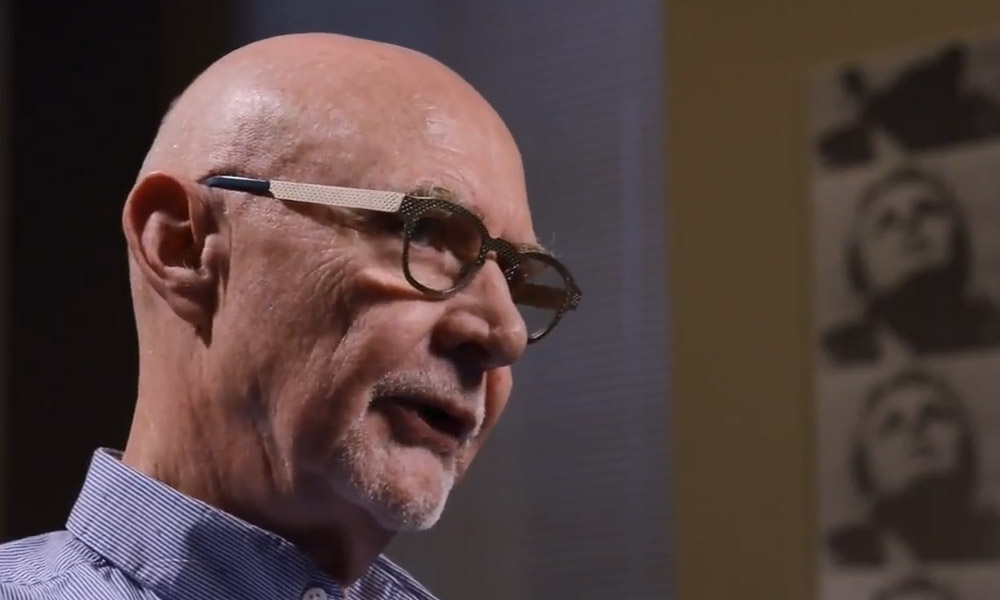

After art critic Douglas Crimp moved to the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan in 1969, he became a regular customer at Max’s Kansas City, a restaurant and art bar on Park Avenue. Max’s had two rooms, one in front and one in back, and members of Andy Warhol’s Factory could reliably be found in the latter. As he passed through the front room, Crimp would greet the “artist-regulars” he had come to know during his first two years in the city, but he found himself inexorably pulled to the back, whose “charged atmosphere” he loved.

The divisions between the rooms “mirrored divisions in the art world that were fairly pronounced in those days, divisions between tough-minded Minimal and Conceptual art and the glam performance scene, between real men and swishes, to use Warhol’s word,” writes Crimp in his new book, Before Pictures (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

The Village Voice has called it a “profound, delectably gossipy memoir,” while the New Yorker termed it an “exhibition-as-memoir,” with its story significantly relayed through the 150 illustrations that fill it.

But Crimp—the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies—rejects the label of memoir, which he suggests doesn’t capture his narrative method and puts the emphasis on him rather than on the historical moment he depicts.

VIEW FINDER: Crimp depicts an era through text and art, such as this image, “Pier 18: Hands Framing New York Harbor,” by John Baldessari and Shunk-Kender.

(Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2014.R.20) / Courtesy of John Baldessari.)

The book “moves from anecdote to criticism to research, back to anecdote, and so forth, and also from my gay life to my art world life,” he says.

Before Pictures was inspired years before it was written, by Crimp’s realization that many of his fellow activists in ACT UP, an advocacy group formed in response to the AIDS crisis, were decades younger than he and so hadn’t experienced gay life in 1970s New York. Writing about his life in that era would be a means of resisting a “revisionist narrative that was being promulgated: that the 1970s represented gay men’s immaturity and led inevitably to AIDS, which in turn made us grow up and become responsible citizens,” Crimp told Out Magazine in September.

After spending his childhood in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, he went to college “as far away as possible in every respect,” he writes, moving to New Orleans and enrolling at Tulane’s School of Architecture. He explored local gay culture and also pivoted from architecture to art history. In 1967 he moved to New York, taking up residence first in Spanish Harlem.

“I moved at a time when New York was virtually bankrupt and rents were cheap and I could imagine myself becoming an art critic by simply joining the art world and participating—and I was able to do that,” he says.

The book, structured around Crimp’s changing addresses, tells the story of his life in the city from the late 1960s through much of the ’70s, concluding with his curation of the 1977 exhibition “Pictures” at the gallery Artists Space. Crimp first became renowned as a critic of the “Pictures Generation”—a group of artists, including Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, whose work reflects the media-driven, consumerist world in which they grew up.

“My own life and aesthetic attitudes reflected the ambivalence and fears that were still operative about homosexuality,” he writes, “about whether art could be a manly enough profession and about what kinds of art qualified as most manly. . . .” He calls the division “between the art world and the queer world” something that he “would negotiate throughout my first decade living in New York City.”

Crimp is the author of five other books, including “Our Kind of Movie”: The Films of Andy Warhol (MIT Press, 2012) and Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics, (MIT Press, 2002). He also edited AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism (MIT Press, 1988), a special issue of the art journal October, later republished as a book. It was the first book-length publication on the cultural meaning of AIDS and propelled Crimp into the AIDS activist movement.

“I first met Douglas through his writing when I was in graduate school,” says Joan Saab, chair of the Department of Art and Art History. When she came to Rochester 15 years ago, she was intimidated to become his colleague—an apprehension that she says was soon dispelled by his generosity to fellow faculty and his engagement of students.

Crimp’s book “brings all the warmth and intellectual rigor of his classroom to the printed page,” she says. “He seamlessly balances his art criticism with his emerging activism, without ever losing his warm and compelling voice. It’s a tour de force.”