Created by CDC microbiologist Frederick A. Murphy, this colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) reveals some of the ultrastructural morphology displayed by an Ebola virus virion. An outbreak of deadly Ebola virus disease, also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, has killed at least 2,800 people in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sierra Leone. The 2014 Ebola outbreak is the largest in history, the first Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and is actually the world’s first Ebola epidemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ebola Q&A: UR researchers share their views

Given the widespread attention regarding the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa, four University of Rochester Medical Center faculty with expertise in viral infections agreed to field questions on this topic.

David Topham, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, is an expert in immune responses to respiratory infections, especially those caused by viruses. His research focuses on how the immune system clears a virus infection and provides long term immunity, in order to design more rational vaccination and treatment strategies.

John Treanor, Chief of the Infectious Diseases Division in the Department of Medicine, is a widely recognized expert in influenza and vaccine research, who helped lead the nation’s efforts to find a vaccine to protect against bird flu and has has long been recognized as a top researcher on more common strains of flu.

Luis Martinez-Sobrido, Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, has spent more than a decade researching the molecular biology, immunology, and pathogenesis of negative-strand and positive-strand RNA and DNA viruses, including Ebola. For example, he was coauthor of a 2003 paper on “The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3.”

Tracey Baas, an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, is senior editor at Science-Business eXchange, a weekly publication from Nature and BioCentury that evaluates novel science and technology with potential translational impact in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical area.

Question: Death rates during outbreaks of Ebola can be as high as 90 percent, depending on the subspecies of virus involved. Why is the Ebola virus so lethal?

Topham: There are no vaccines, no treatments. And unfortunately, like a lot of viruses that enter humans from a zoonotic (animal) source — in this case apparently from fruit bats — they can often be more pathogenic, and more unpredictable than viruses that have been circulating longer in humans.

Martinez-Sobrido: When we are exposed to viruses that have been circulating in humans, like the common seasonal influenza, we have some preexisting immunity to protect us against these viral infections. But when we are exposed to a new zoonotic virus, like Ebola, with no preexisting immunity, it is that much easier for the virus to replicate. In this case, Ebola also induces a cytokine storm. (Cytokines are proteins that help modulate our immune response.) This is responsible for the pathogenesis and is what kills you. It is our own immune system, which wants to protect us from the virus, that is actually harming us.

Question: Why is this particular outbreak proving so difficult to contain?

Topham: In the past, Ebola outbreaks have affected relatively small populations in isolated areas. The best control measure is quarantine, so in the isolated areas it was effective to just circle it off. This outbreak is occurring in populated areas where it is socially, geographically and politically difficult to put quarantine into place and have it be effective.

Ebola is also a relatively rare disease. A big factor in the current outbreak is that Ebola is occurring in countries that haven’t seen it before.

Question: Given the scope of this outbreak, is there a need for the U.S. government to devote more funding to developing vaccines or antiviral drugs?

Baas: There are developmental therapies on the shelves that could be potentially taken forward, but where’s the money going to come from? Businesses are hesitant to invest because therapies would be targeting a small group of people. The government is getting somewhat involved, but philanthropies and academic sources have also been coming forward. In recent days the Gates Foundation has put together $50 million to support the emergency response to Ebola. A group of people from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has put together $24.9 million for the antibody therapy that is being worked on. (BARDA, in the Office for Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, provides an integrated, systematic approach to the development and purchase of the necessary vaccines, drugs, therapies, and diagnostic tools for public health medical emergencies.) Another group, involving NIH, GlaxoSmithKline, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, has come up with $4.7 million to fund trials of a vaccine. (The vaccine is based on an attenuated strain of chimpanzee adenovirus. It is used as a vector to deliver benign genetic material derived from the Ebola virus to human cells but does not replicate further).

Topham: The primary reason the U.S. needs to be interested in this is a humanitarian one.

Also, the instability that the virus has caused both politically and economically is going to generate political issues for us in the affected countries, which are going to be a threat and problem in ways we cannot possibly predict.

These are poor countries, with tenuous governments to begin with, tenuous health care and fragile economies. Just the stigma of having this in your country is enough to break down some of these structures, which could lead to political instability. I think that’s going to have more consequences than the virus itself.

Question: What should be the role of pharmaceutical companies in developing vaccines or antivirals to counteract Ebola?

Treanor: The relative lack of involvement up until now on the part of the industry is actually pretty understandable. The funding that is being committed by the Gates Foundation and others will create therapies which will be available long after this outbreak is terminated, and they will sit in freezers for years and years — perhaps decades — and potentially never be needed until they are outdated, and then there will be a new outbreak. It’s just extremely difficult to have a sustainable product development pathway for something that happens so infrequently. A mainstream pharmaceutical company is not going to be able to do that. BARDA (The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority in the Office for Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services), or an organization like that, needs to take the lead in this. Because of the weird epidemiology of Ebola, it is more appropriately handled by government.

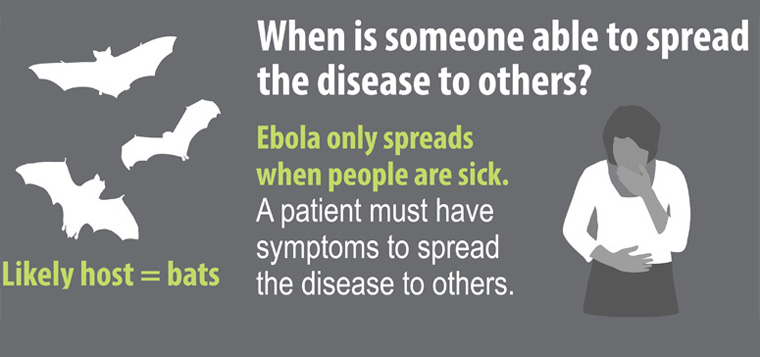

The other element is that this particular infection — at least as far as we know — looks like something that should be containable with very simple practices that don’t require sophisticated antivirals. In theory we should be able to contain it with standard health practices. Ebola transmission does not occur from asymptomatic individuals. As long as that is true we should be able to use very straightforward strategies to control outbreaks.

However, a vaccine would be worth pursuing for health care providers. The high rate of mortality among health care providers is an impediment to controlling outbreaks. New outbreaks are unpredictable, so you could make an argument for vaccinating health care workers in areas where Ebola is endemic.

Question: if Ebola emerged in the United States, would it be easier to control here than in a developing country?

Treanor: It would be easier to control in a setting where sufficient health care resources are available. The only qualifier is that the entire world experience with Ebola, I would guess, is less than 10,000 cases in recorded history. Could there be things we don’t know at this point? I would say probably yes. However, based on what we do know, Ebola control should be much easier in a setting where there is a developed health care system.

Question: How do pandemics — global disease outbreaks — occur?

Topham: A common feature of pandemics, almost by definition, is that they involve a novel pathogen to humans. There’s no immunity, and that creates a higher proportion of susceptible subjects.

Treanor: The other common feature of all pandemics involving emerging viruses is that they come from animals, not humans. Essentially every single example of an emerging virus that causes widespread disease among humans is something that started in animals.

Question: What is it about viruses in general that make them such a challenge?

Martinez-Sobrido: When you are dealing with viruses that cause hemorrhagic fever in humans, for example Ebola virus, a very high level of laboratory biosafety (BSL4) is required and it is more difficult to work under these conditions.

Treanor: Viruses use the host cell metabolism to replicate, which makes it difficult to find a magic bullet that only affects the virus and not the host. With bacteria, it’s little easier because they have a unique metabolism that you can target.

Topham: The ability of viruses to change rapidly is one of our biggest challenges, especially in HIV and influenza. They are always a moving target.

Treanor: Viruses can mutate quickly and evolve away from almost anything you try to do. That’s always a challenge with vaccines or antiviral approaches. Viruses are very clever at escaping from whatever you throw at them.