Can lost vision be restored?

Leveraging neuroscience, optics, and healthcare, URochester researchers are at the forefront of understanding vision loss and restoring eyesight.

Almost everyone knows someone who wears glasses or contact lenses. Correcting blurry vision is common, especially among aging adults. The National Institutes of Health estimates that nearly 93 percent of people over 70 wear lenses. Unfortunately, not every visual problem associated with aging is so easily corrected.

“Vision is complicated, and we don’t yet have a complete understanding of how it works, let alone how to prevent these complex diseases,” says Juliette McGregor, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “Vision is a really fundamental sense that helps us with the activities of daily life, but it also brings us a lot of joy. Sharing a smile or seeing a beautiful sunset are important not just for independence, but also for our well-being. Researchers are working hard to create new technologies and treatments designed to allow people with vision loss to regain some visual performance.”

Researchers have found that in other animals, such as zebrafish, the eye and brain can regenerate after injury, but in humans, this type of regeneration or regrowth does not happen. Cells in the back of the eye, that detect light, process visual signals, and then send that information to the brain, are vulnerable to damage, especially in common age-related conditions like macular degeneration and glaucomas. Once these neuronal cells are damaged and stop working, they cannot regrow or be repaired.

“Ideally, we would prevent these diseases, but we are not yet in a position to do so,” says McGregor. “We can try to slow disease progression, but once neuronal cells are lost, there is nothing we can do beyond helping people to adjust to visual impairment. Research has expanded our understanding of how we see, but there is still much to learn, and whether we can restore high-quality vision after it has been lost is being actively explored.”

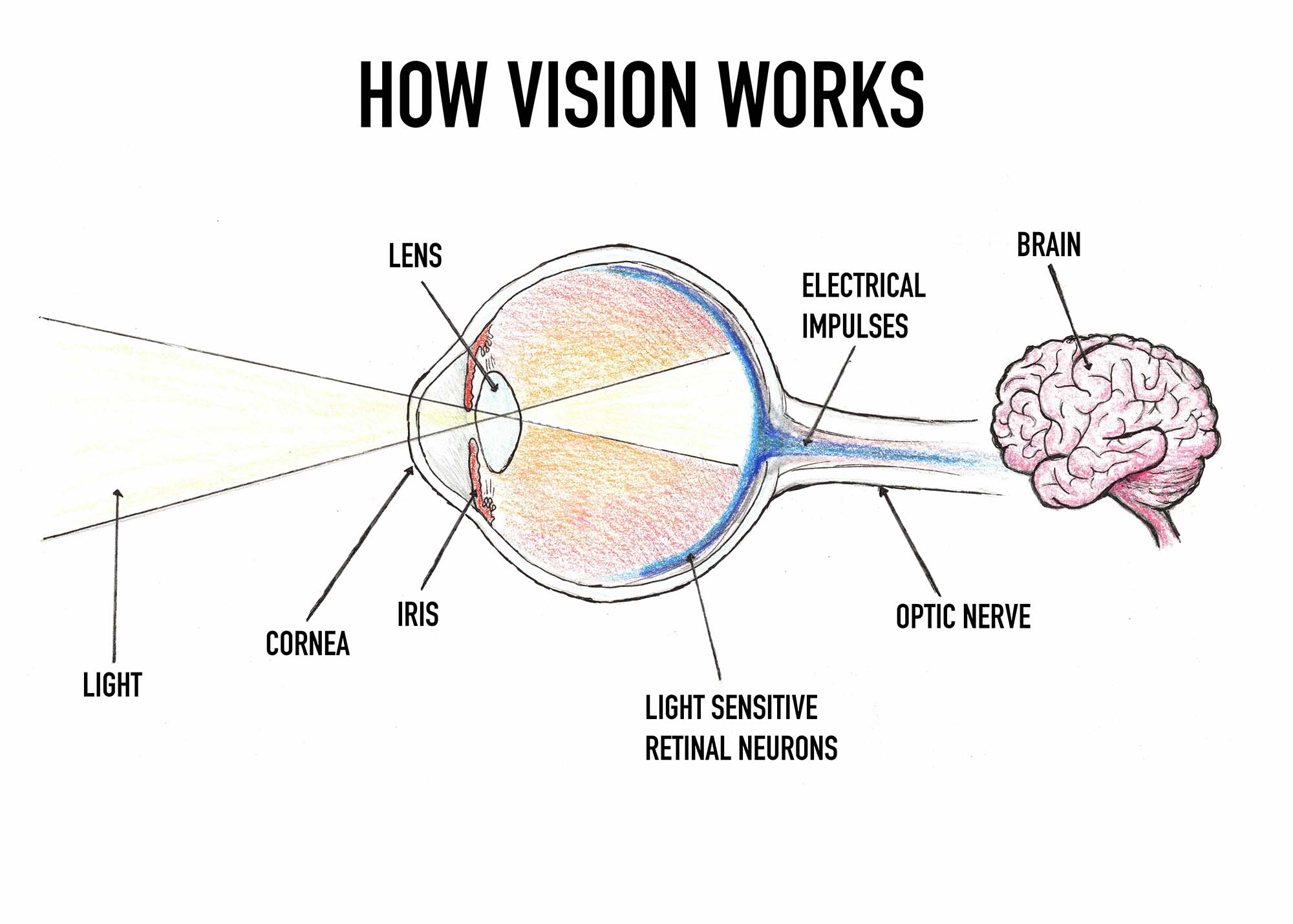

How vision works

“The cornea and the lens focus light just like a camera lens.”

Of course, vision, the eye and its relationship to the brain are more complicated than a camera. Yet this physical object shares some similarities with this intricate sensory system. Like the camera, light passes through the focusing elements of the eye and falls onto a light sensor: the light-sensitive photoreceptor cells in the retina. The iris controls the amount let in. The retinal neurons do some initial processing and send signals encoding this visual information up to the brain.

Modern smartphone cameras take multiple frames and can use the motion of the image to compute a higher quality output. Eye movements are also crucial in human vision. Researchers in the Active Perception Lab at URochester have found that small involuntary eye movements are key to how we see. “Eye movements contribute to vision by transforming spatial information into temporal changes on the retina. These input signals strongly drive neuronal responses,” says Michele Rucci, a professor with the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the University’s Center for Visual Science (CVS).

What is blindness?

There are often misconceptions around the idea of blindness. According to McGregor, it’s better to think of a spectrum of visual impairment, ranging from minor problems to no light perception. The type of vision loss a person has—and the impact that loss has on their daily life—depends on which structure of the eye or the brain is affected, the severity of the problem, and the patient’s ability to adapt.

In many cases, there are treatments available to minimize vision loss. But for others, there is little that medicine can currently offer beyond assistive support. It is particularly challenging to treat disorders impacting the neurons in the eye and brain. Several labs at the University focus on understanding the causes of vision loss, including at the Flaum Eye Institute (FEI) and the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience. However, the breakdown of retinal neurons is still mysterious in many ways.

Advanced genetic and cell biological tools allow fellow URochester researchers with the Libby Lab to investigate the multiple factors that drive neuronal dysfunction and death in the common age-related disease glaucomas. Meanwhile, the Singh Lab uses human stem cells to model age-related macular degeneration (AMD). By examining genes associated with both AMD and rarer inherited forms of blindness called macular dystrophies, URochester researchers have identified a key protein involved in the early stages of the disease. “Current treatments for AMD have limited efficacy and often come with significant side effects,” says Ruchira Singh, with the FEI and CVS. “Our research aims to identify novel therapeutic targets that could potentially halt the progression of this disease.”

What basic research can tell us about vision restoration

What goes awry and causes vision to break down can happen at any stage of life and for a variety of reasons—genetics, environmental exposures, injury, or progressive disease—and in any part of the visual system.

An issue in the front of the eye, with the lens and cornea, is potentially treatable with glasses or surgery. David Williams, the William G. Allyn Professor of Medical Optics at URochester, developed a method to accurately measure and correct the optical imperfections in the eye, allowing for the development of better corrective lenses—both in glasses and contacts. This research also helps improve laser refractive correction surgeries, such as LASIK.

CVS director Susana Marcos is using advanced imaging to create personalized eye models to guide the selection of ocular corrections. Her lab has also created technologies to allow patients to experience the visual outcomes of cataract surgery prior to the procedure, so they can choose the intraocular lens that best meets their needs.

This same technology—first developed by Williams’ team at URochester—also allows scientists to image single cells inside the living eye. Jesse Schallek, an associate professor of ophthalmology and of neuroscience, adapted this tool, known as adaptive optics ophthalmoscopy, to reveal the dynamics of previously invisible immune cells infiltrating retinal tissue and responding to threats that may jeopardize vision.

Amazingly, it is also possible to record the activity of individual neurons in the living eye with adaptive optics, which presents new opportunities for evaluating the performance of next-generation therapeutics. McGregor’s lab specializes in using these advanced retinal imaging approaches to test and optimize new vision restoration therapies for retinal degenerations. Their aim? Ensuring that the treatments entering clinical trials have the best chance of success.

Seeing again: A vision of the future

Developing new therapies requires a team approach with contributions from a range of scientific disciplines.

McGregor leads an NIH, National Eye Institute Audacious Goals Initiative Project to restore vision by replacing the light sensitive cells in the retina that are lost due to disease, with new cells grown in a lab. This work includes pioneering new surgical approaches to deliver these replacement cells to the eye in collaboration with FEI vitreo-retinal surgeons.

The team has previously delivered cells into the eye on biodegradable tissue scaffolds; this year, they have developed a new minimally invasive surgical approach using a biocompatible viscous delivery vehicle. McGregor and neuroscientist collaborators at the University of California, Berkeley, have also recently showed that these lab-grown replacement cells appear able to connect up with the types of cells in the eye that mediate our ability to discriminate fine detail, like when reading text or seeing facial expressions.

Once light sensitivity has been restored to the retina, the signals need to be interpreted by the brain—and the usability of restored vision may depend on the brain’s ability to adapt to these new signals. Damage to the visual cortex, such as after a stroke, can also cause vision loss. URochester researchers like Krystel Huxlin, associate director and co-director of training for CVS and the James V. Aquavella Professor of Ophthalmology, have shown that it is possible to “retrain” the brain to regain vision and reduce the region of vision loss.

“This is an exciting time. Current therapies aiming to restore vision to patients with retinal degenerations are already showing some promising results in clinical trials—including the ability to read a sign or locate an object. But it’s not yet the kind of vision that you and I experience day to day,” says McGregor. “Down the road, we’d like to restore high-quality vision so that patients are able to see a friend’s smile or appreciate a sunset again and we are hopeful that the regenerative technologies we are investigating will bring that goal within reach.”