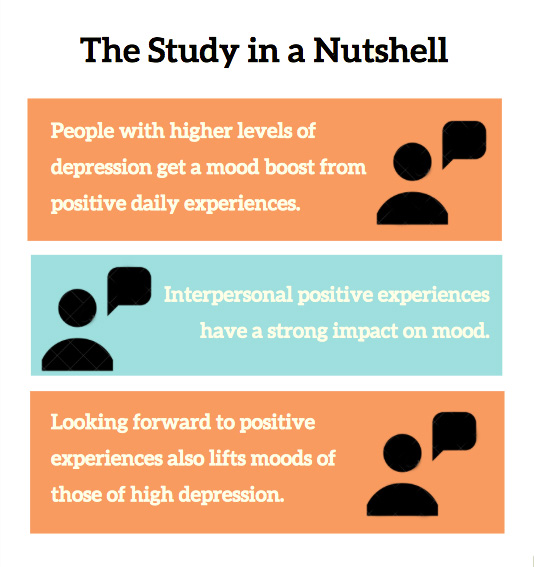

Those suffering from dysphoria—feeling unhappy and experiencing elevated depressive symptoms—respond to positive experiences with a marked reduction in their depressive mood.

A recent study in the Journal of Clinical Psychology found that experiencing or even just anticipating uplifting events in daily life was related to feeling less depressed that same day.

The study, conducted by University of Rochester assistant professor of psychology Lisa Starr and Rachel Hershenberg, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University, found that a decrease in depressive mood was especially marked when the experience included interpersonal uplifts, such as participating in fun activities with friends or family.

“It’s the social activities—positive, everyday experiences that involve other people—that may be most likely to brighten the mood of those struggling with depression,” says Starr.

“It’s the social activities—positive, everyday experiences that involve other people—that may be most likely to brighten the mood of those struggling with depression,” says Starr.

A number of laboratory-based studies suggest that the moods of people with depression are relatively unresponsive to positive stimuli. In other words, when people with depression experience a positive event in the laboratory—like receiving a financial reward—their mood is unlikely to improve markedly. The crux here is that laboratory research doesn’t always translate to real-life settings.

The Rochester study is one in a growing number of studies to examine how real-life events with direct relevance to the study participants affect their moods. The authors wanted to know if people with elevated levels of depression felt better when good things happened to them. The answer is simple—yes. The same is true for the expectation of good things to come.

“Consistent with previous data, we found that people with higher levels of depression are less likely to anticipate that tomorrow will include positive experiences,” says Starr. “However, when they do have moments of anticipating positive next-day experiences, it’s linked to reductions in daily depressive symptoms.”

The study included 157 young adults of whom two-thirds had mild, moderate, or severe depressive symptoms. The remaining third had no symptoms, allowing the authors to examine whether the level of depressive symptoms changes the way people respond to positive experiences. The study subjects completed a two-week online diary, tracking their mood as it related to recent and anticipated positive events in their lives–like time spent with friends, or exercising.

Funded by the University of Rochester, the study that is attracting interest in the field, including a positive review in Psychology Today.

Those with greater baseline dysphoria, that is to say those who reported higher levels of depressive symptoms at the onset of the study, showed stronger associations between daily uplifts and lower daily depressive symptoms, particularly when the uplifts were interpersonal in nature. Generally speaking, those who are depressed are less likely to anticipate positive next-day experiences. However, when they did anticipate positive experiences, they experienced greater reductions in their depressed mood.

“The findings have really important implications for treatment and are especially compatible with a treatment model called Behavioral Activation, which suggests that if you can help depressed people to engage in positive experiences—despite their low motivation to do so—their mood may improve,” says Starr.

In other words: If you’re feeling seriously blue—make a concerted effort to do something fun with friends.