Rochester historians are chronicling the history of the world’s glacial regions—and human responses to their rapid disappearance.

While some thrive on the energy, sounds, and smells of large metropolitan areas, Tanya Bakhmetyeva and Stewart Weaver decidedly do not. Equally, lush tropical beaches hold little sway for them. Instead, cold, sparse landscapes are their ticket.

Kitted out with ice picks, ropes, harnesses, crampons, carabiners, and trekking poles, they have been collecting information in high-altitude mountain ranges together since 2017, sometimes at elevations of 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) and higher. Frequently, their research destinations are rich in vista but poor in vegetation.

The personal and professional lives of Weaver, a University of Rochester professor of history, and Bakhmetyeva, a professor of instruction in the Department of History and the associate director of the University’s Humanities Center, regularly collide. Married for 13 years, the two often collaborate on projects rooted in the history of climate change. Their research alternatively takes them deep into historical archives or high atop mountain ranges, including the Austrian Alps in Europe, and the Himalayas and the Pamir Mountains in Asia.

“People ask us all the time how we can live, work, and then travel together,” Bakhmetyeva says with a laugh. “For us it’s great.”

Until the disruption caused by COVID-19, the couple had spent the summers of 2018 and 2019 collecting oral histories from the people in Ladakh, a trans-Himalayan region in the far north of India that is experiencing drastic climate change at an extraordinary pace. In 2019, Weaver won funding as an Andrew Carnegie Fellow to work on the “Climate Witness: Voices from Ladakh” project, an effort to preserve the rich culture and history of the locale and its people in oral history form—before it’s too late.

In his Carnegie application, Weaver describes the harrowing backdrop to their research—torrential rains that wrecked the region on August 5, 2010: “A violent cloudburst dumped fourteen inches of rain on Ladakh, accustomed to getting just three inches of rain in a year.”

The results in Leh, the main town, were catastrophic, he writes: 255 people killed, more than 800 injured, and thousands left homeless. Barely five years later, flooding recurred on an even wider scale, destroying buildings, roads, fields, and orchards all over the region.

Yet while Ladakh “suffers from too much water, it also suffers from too little,” says Weaver. Declining snowfall and glacial recession have diminished the region’s water reserves and wreaked havoc on the local agriculture.

The couple’s oral history work in Ladakh didn’t go unnoticed. In 2021, together with Daniel Rinn, who had earned a PhD in history from the University a year earlier, their project won the Public Outreach Project Award from the American Society for Environmental History.

From pastime to profession

As a teenager, Weaver lived with his family for several years in New Delhi, where his father was posted as an educational consultant for a foundation. Mountain ranges beckoned.

“I’ve been a hiker and mountain climber all my life,” says Weaver—first in the Himalayas with his family, later as an adult in the mountains of Wyoming, Colorado, California, and now Europe. He’s been a keen reader of mountain and mountaineering literature as long as he can remember.

Weaver would later add to the genre himself, coauthoring with Maurice Isserman Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (Yale University Press, 2008). The book not only won the National Outdoor Book Award for History and Biography that year, it also marked a departure from Weaver’s previous research specialty of British history, which he taught at Rochester for many years.

“Increasingly over time, I’ve become more interested in environmental history, the history of exploration, and now most recently, the history of exploration and science,” Weaver explains. “Now, I’d say I’m a historian of mountains and alpinism.”

Meanwhile, Bakhmetyeva’s route to the mountains was slightly more winding. Born in Ukraine to Russian parents, she and her family moved back to what was then the Soviet Union, coming to the United States in 1995. Her first book was about a Russian émigré and her famous 19th-century Parisian salon. Today, Bakhmetyeva jokes that her academic interests have moved from the indoors to the outdoors.

At Rochester, she’s taught a course on the politics of nature, focusing on issues of race, gender, and the environment. She has a particular research interest in ecofeminism, a branch of feminism that examines the interaction of gender and the environment.

Part of that research was a project about hunting. Specifically, Bakhmetyeva, a vegetarian, was writing about the role of hunting and nature and its importance in Soviet diplomatic relationships under Nikita Khrushchev, the first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964. Taking foreign leaders and diplomats on hunting expeditions, Soviet apparatchiks used these outings, she argues, to display their “marksmanship and physical prowess” to present themselves to their foreign counterparts as “potent leaders and desired allies.”

One day, while working in the office she shares with Weaver in the attic of their Rochester home, Bakhmetyeva was reading about a historical character, Nikolai Krylenko. Besides being a regular hunter in earlier times with Vladimir Lenin (and as a Soviet politician proved one of the cruelest Russian Bolshevik revolutionaries), Krylenko was also a serious mountaineer who was a climbing leader in the famed 1928 German-Soviet Fedchenko expedition. Incidentally, that exploration was the first to survey the enormous Fedchenko glacier completely, determine its course, and establish its astonishing length. Her interest piqued, Bakhmetyeva kept reading. Soon she stumbled across a German climber-scientist, Richard Finsterwalder, whose name sounded somehow familiar.

She recalls, “I tuned to Stewart and said, ‘Wait, isn’t this guy I’m reading about here in the scientific mountain expedition one of your guys, too?’”

Indeed, Weaver had written about Finsterwalder decades earlier in the context of a 1934 German expedition to Nanga Parbat, the ninth-highest mountain in the world, located in Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Finsterwalder would become the couple’s first point of professional convergence.

“From that we started unraveling the story of glaciers and it snowballed from there,” says Bakhmetyeva. As the couple charted more environmental history projects, one geological feature in particular caught their attention—ice.

“Of all the ominous signs of our climate crisis, none has so strong a hold on the public imagination as the loss of ice, as the collapse of the polar ice sheets, and the ever-accelerating melt of the world’s glaciers,” the duo told fellow historians in 2023 at the History of Science Society meeting in Chicago.

In some respects, glaciers have become the latest endangered species, a bellwether of global warming. Climate scientists like to point out that ice has no political agenda—it simply reacts to external forces. But the two Rochester historians argue for another dimension: “Glaciers shape not just our physical landscapes, but also our social and cultural ones,” says Weaver, noting that the ways in which societies have understood and interpreted glaciers have changed throughout history.

A new area of inquiry—the ‘ice humanities’

While climate scientists are documenting the physical loss of the world’s glaciers and are racing to find ways to slow it, environmental historians like Bakhmetyeva and Weaver are collecting and preserving human history—and the history of glacial science—in the face of rapid climate change. The emerging area of inquiry has its own name: ice humanities, a term popularized by two academics, Klaus Dodds and Sverker Sörlin, in their book Ice Humanities: Living, thinking and working in a melting world (Manchester University Press, 2022).

It can be confusing, admits Bakhmetyeva, who says the couple has been asked numerous times “what exactly” they—as historians—have to do with glaciers, which seem to fall squarely into the purview of geologists and environmental scientists.

The new field, which belongs under the larger umbrella of the environmental humanities—itself a consolidation of several fields that happened about 25 years ago—is trying to advance knowledge of how glaciers (and with it snow, permafrost, sea ice, and icebergs) came to be understood, and to offer a cultural perspective on the role of glaciology (the study of glaciers) in climate studies. In other words, historians document the natural history of ice, its socio-historical importance, and the work of glacial scientists throughout the ages. “Ice humanities” describes a plethora of humanistic inquiries by artists, historians, philosophers, and literary scholars alike, with the idea of throwing wide open the doors to scholarship that transcends the separate silos of classic academic disciplines and allows for meaningful transdisciplinary research.

Part of Weaver’s and Bakhmetyeva’s research, for example, seeks to answer how Tajiki people, and indigenous communities in general, think of glaciers, at times disconnected from the larger, global questions about climate change. How have they projected their own cultural history of Tajikistan onto the world’s largest glaciers? What role do glaciers play in the cultural imagining of the Pamiri people?

Beyond the artistic and cultural meaning, the couple studies how glaciological knowledge was produced historically, how it gained scientific credibility, and what political forces shaped the study of glaciers as a distinct discipline.

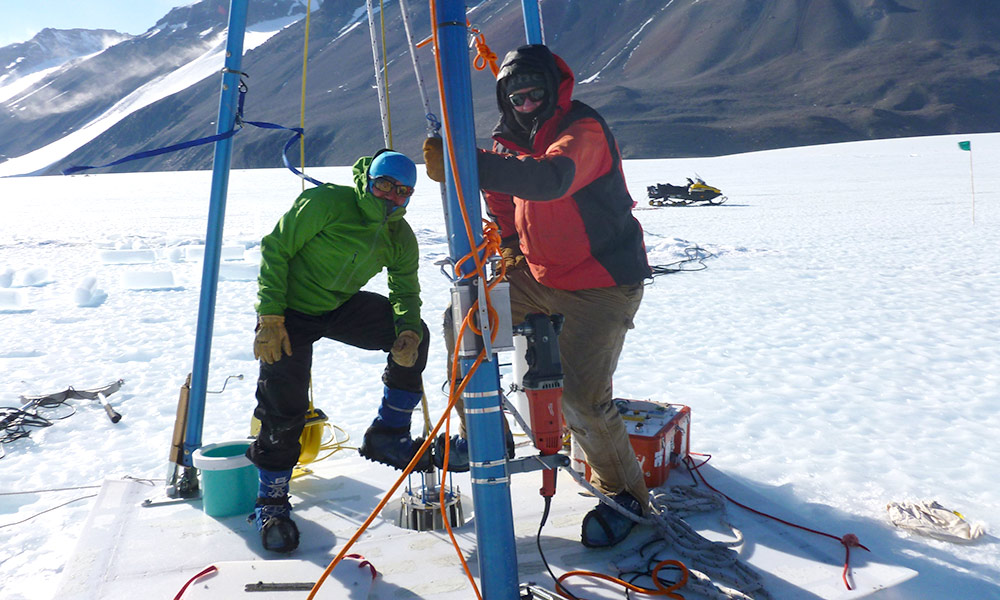

Of particular interest to ice historians are key moments in the 19th and early 20th centuries that laid the foundation for modern glaciological and climate change research. One such moment, Weaver and Bakhmetyeva argue, was the emergence of scientific glacial mapping.

The founding fathers of glacial cartography

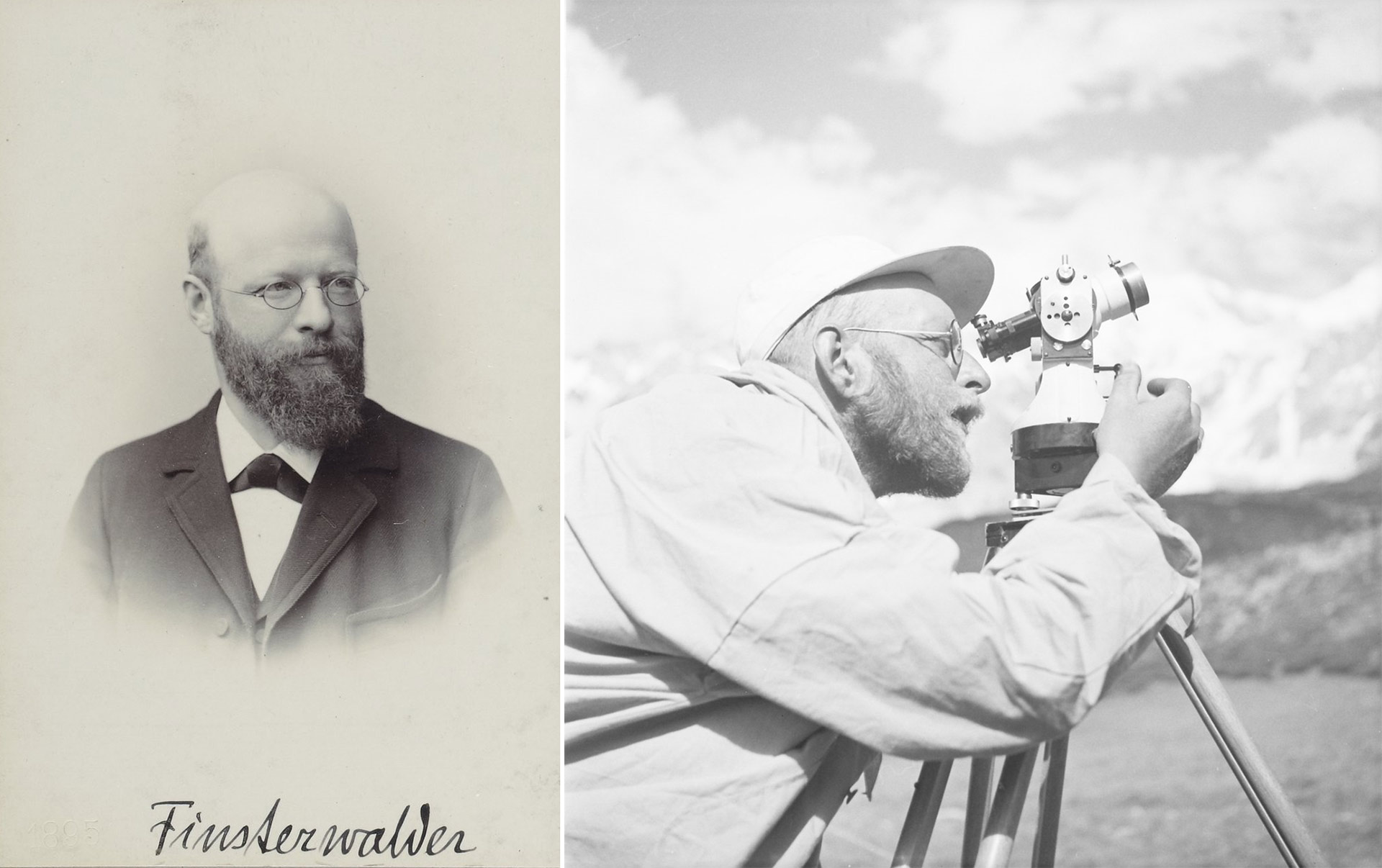

For Weaver, researching the history of glacial science marks a return to research he originally undertook nearly 20 years ago for Fallen Giants. The name Finsterwalder keeps popping up again and again in the couple’s research.

Avid outdoorsmen, mountaineers, and master glacial mappers, the Bavarian mathematician Sebastian Finsterwalder (1862–1951) and his son, Richard Finsterwalder (1899–1963), brought more than just their apt surname to the profession (the German root word “finster” translates to “dark” or “gloomy,” while “wald” means “forest”). They also successfully applied improvements in early remote sensing technology to high-altitude photogrammetric surveying, including using stereo photogrammetry from which they created early 3D images for their glacial cartography.

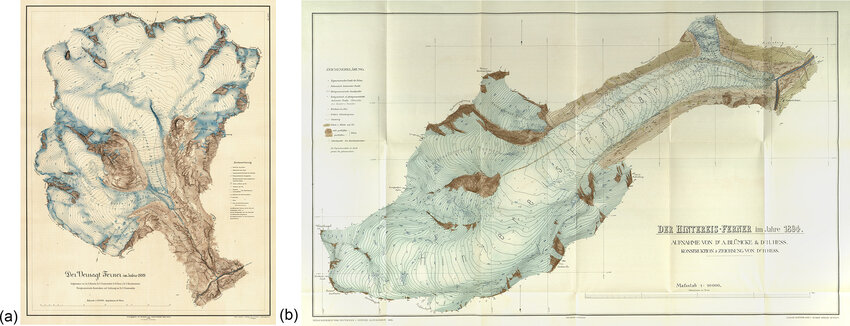

The elder Finsterwalder was the first to draw a topographically accurate map of a glacier, the Vernagtferner in Austria, in 1889.

“That’s the moment when glaciers became scientific objects, and that glacier map became the basis for climate research, available for longitudinal studies,” notes Bakhmetyeva. Indeed, glacial climate scientists today still refer to these 135-year-old Finsterwalder maps.

“For all their pioneering scientific photogrammetric accuracy, they came up with very beautiful maps that were informed by a deep knowledge of the older ways of rendering glaciers as beautiful, magnificently sublime things,” says Weaver about the founding fathers of glacial cartography.

Meanwhile, Bakhmetyeva, drawing on her background in gender studies, traces connections between early glacial science, glacial cartography, and an “explicitly masculinist ethos of heroic adventure” in the Finsterwalders’ work, which went beyond mere mapping.

“To earn authority as a glaciologist took becoming a mountaineer and putting one’s body on the line as a vicarious scientific instrument,” the duo argues in a forthcoming paper. Before the advent of photography, it also took becoming an artist to be able to preserve the evidence of firsthand observation, and to document the extent of glacial movement over time.

About a hundred years later, the Rochester historians are now retracing many of the Finsterwalders’ physical expeditions and scientific contributions—from the Alps, to the Himalayas, and Pamirs.

“We’ve been to the very huts where the older Finsterwalder stayed, the very valleys that he hiked with his equipment to chart, survey, and map these glaciers,” says Weaver. Being on site, he notes, provides meaningful context to the diaries of Sebastian Finsterwalder’s Alpine excursions, maps, and diagrams. “It adds a whole new level of intuitive understanding and actual physical comprehension of the landscapes he explored,” Weaver says.

Tracing the history of the Fedchenko Glacier

The couple’s latest research takes them to the remote Pamir Mountains, located mostly in the former Soviet republic of Tajikistan with fringes that extend into Afghanistan, China, and Kyrgyzstan.

The mountains are home to thousands of glaciers, and it’s difficult to overstate their importance as the region’s natural water towers. According to NASA, nearly 90 percent of people in Central Eurasia rely on melted mountain waters for agriculture, energy, and drinking water.

Even among the range’s myriad glaciers, one stands out: the 48 mile-long Fedchenko, the one that the Soviet-German team measured and surveyed in 1928, and the world’s longest non-polar glacier. (As part of Tajikistan’s ongoing de-Russification program, the glacier was renamed Vanch-Yakh in 2023, but most sources are still using the old, historical name.)

Armed with a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) research award, Weaver and Bakhmetyeva joined the PAMIR Project, an international collaborative dedicated to developing an interdisciplinary understanding of the high-mountain region of Asia.

“At a time when glaciers are fast disappearing, we return by way of the Fedchenko to the moment of their appearance in both the scientific and cultural imagination,” the duo wrote in their NEH application. The idea is to offer a cultural perspective on the role of glaciology in climate change studies—subjects that have been “hitherto neglected by humanists and humanistic social scientists,” they argue.

In 2023, at the official kickoff meeting for the PAMIR Project in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, the couple worked alongside geographers, cartographers, glaciologists, biologists, and geophysicists. Yet, a visit to the actual glacier has so far remained elusive for them. The region is remote and hard to access—on foot it takes weeks to reach, and evacuations are nearly impossible, notes Bakhmetyeva.

Helicopters seem the obvious answer, but politics got in the way. The lack of Tajiki pilots able to fly them and the subsequent wrangling over Swiss pilots flying in Tajiki airspace meant the plan turned into a “bureaucratic political storm” that has been dragging on for two years now, according to Weaver.

What makes the glaciers in the wider Pamir region so interesting to scientists and humanists alike is the curious fact that they melt and recede much more slowly than other glacial regions in the world. In the 1990s, scientists discovered an idiosyncrasy—the so-called Karakoram Anomaly (named after the eponymous mountain range)—whereby glaciers in the adjoining mountain ranges of the Karakoram and the Pamir remain largely unchanged, or even show small ice gains, in contrast to the marked retreat of other glaciers around the world.

“There’s something relatively stable here that intrigues everyone,” says Bakhmetyeva. “Understandably, there’s a lot of desire to understand it.” The duo is hoping to finally set foot on the glacier some time next year.

The timing may prove auspicious: The United Nations has designated 2025 as the launch of a “Decade of Action” to preserve glaciers. Dushanbe is at center, playing host to a large symposium on glacier protection.

Meanwhile, on the so-called roof of the world, 350 square miles of cold and unspoilt Fedchenko are beckoning, a call that Weaver and Bakhmetyeva find hard to resist.