In 2016, Timothy Dye, a professor of public health sciences at the University of Rochester, traveled with a team to Puerto Rico to help local medical personnel deal with a Zika epidemic. In the process, they interviewed residents on their attitudes and living conditions, ending up with a voluminous amount of data.

Unlocking big data

A Newscenter series on how Rochester is using data science to change how we research, how we learn, and how we understand our world.

When they returned home, Dye approached Jiebo Luo, an associate professor of computer science at Rochester who specializes in machine learning, data mining, and biomedical informatics. “Our operation is involved in converting research findings into applications, and that means making sense of massive amounts of data” says Dye. “We knew Jiebo Luo was the right person for the job.”

Dye and Luo are just two of the more than 40 faculty members from across the University whose research either relies on or furthers the new and fast developing field of data science. To harness their strengths, and facilitate collaborations such as the one between Dye and Luo, the University launched the Goergen Institute for Data Science in 2016.

The institute is part of a $50 million investment by the University in the new field. Located in the state-of-the-art Wegmans Hall, it serves as a hub for research, education, and external partnerships. So far, 14 new faculty have been hired in areas in which data science plays a critical role, including bioinformatics, biomedical engineering, brain and cognitive sciences, business and economics, computer science, mathematics and statistics, physics, and political science.

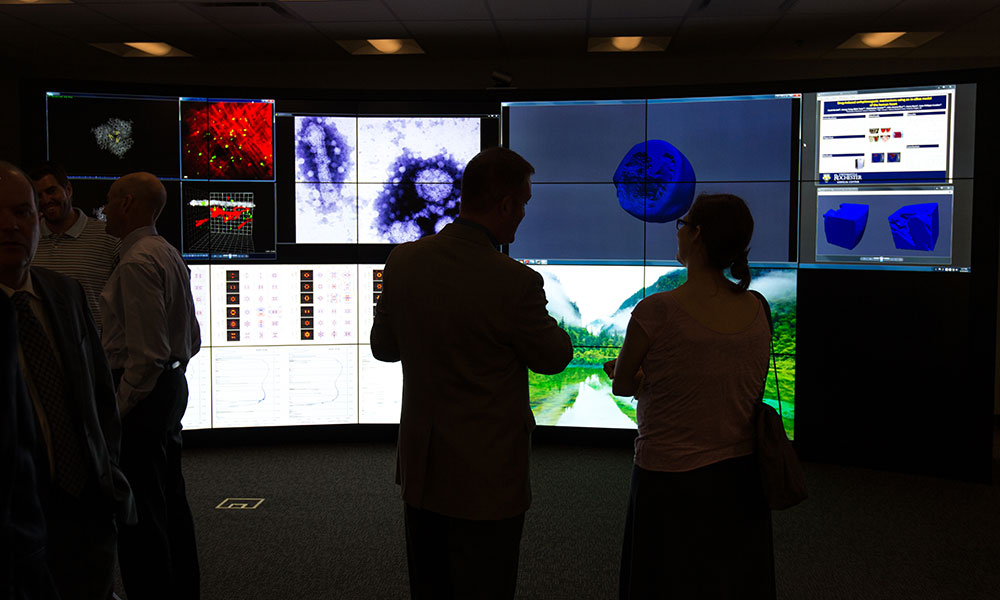

Henry Kautz, the Robin and Tim Wentworth Director of the institute, notes that Rochester enjoys strengths in both faculty and technological resources. “The University brings considerable assets to the new field of data science, including the IBM BlueGene/Q supercomputer and the expertise in our Department of Computer Science,” he says. “Plus, the VISTA Collaboratory allows researchers to visualize and analyze massive data sets in a 1,000 square-foot laboratory.”

External partnerships make up another main focus of the institute. Scott Steele, deputy director of the institute, says, “We’ll collaborate with virtually anyone who needs to make sense of tremendous amounts of data.”

The institute serves as a resource for companies and organizations in a range of fields, including retail, medical, science, and law enforcement. While those partners will gain valuable insights to help their operations, relationships benefit the University, as well.

“The collaborations give our faculty opportunities to apply—and even advance—their research in real-world settings,” says Steele. “And each partner is required to take on at least one of our students as an intern to help with the project.”

Bob Maybee, the vice president of customer insights at Wegmans Food Markets, says Wegmans has taken on two interns to help the company use processed data to better serve its customers.

“The opportunity to work with the institute is invaluable, not only to Wegmans, but to the interns we have working on these projects,” he says. “We have been able to explore new data models through the eyes of talented young people who bring a new perspective. They, in turn, get to apply what they have learned, while building relationships and experiencing real-world business interactions.”

Research that relies on solid data science can upend common assumptions, leading to better business strategies and, in a public health crisis such as a disease epidemic, better policies.

Using recorded interviews from Dye’s team, Luo is now working on a voice-recognition program that will efficiently provide valuable information about public attitudes, and give medical personnel a clearer picture of the physical environments in which the local populace live.

“In Puerto Rico, health officials were warning people about the presence of used tires that gather water and provide a breeding ground for mosquitos,” says Dye. “We found that tires weren’t a problem, at all. Instead, the people typically had planters that filled with water and attracted mosquitos. Consequently, the advice from the health officials was meaningless.”

As Dye and his team collect more Zika-related data from under-developed regions of the world, the algorithm used in Luo’s software will only continue to improve.