Smithsonian Magazine highlights the role of a Rochester historian and archaeologist in unearthing Bermuda’s colonial origins.

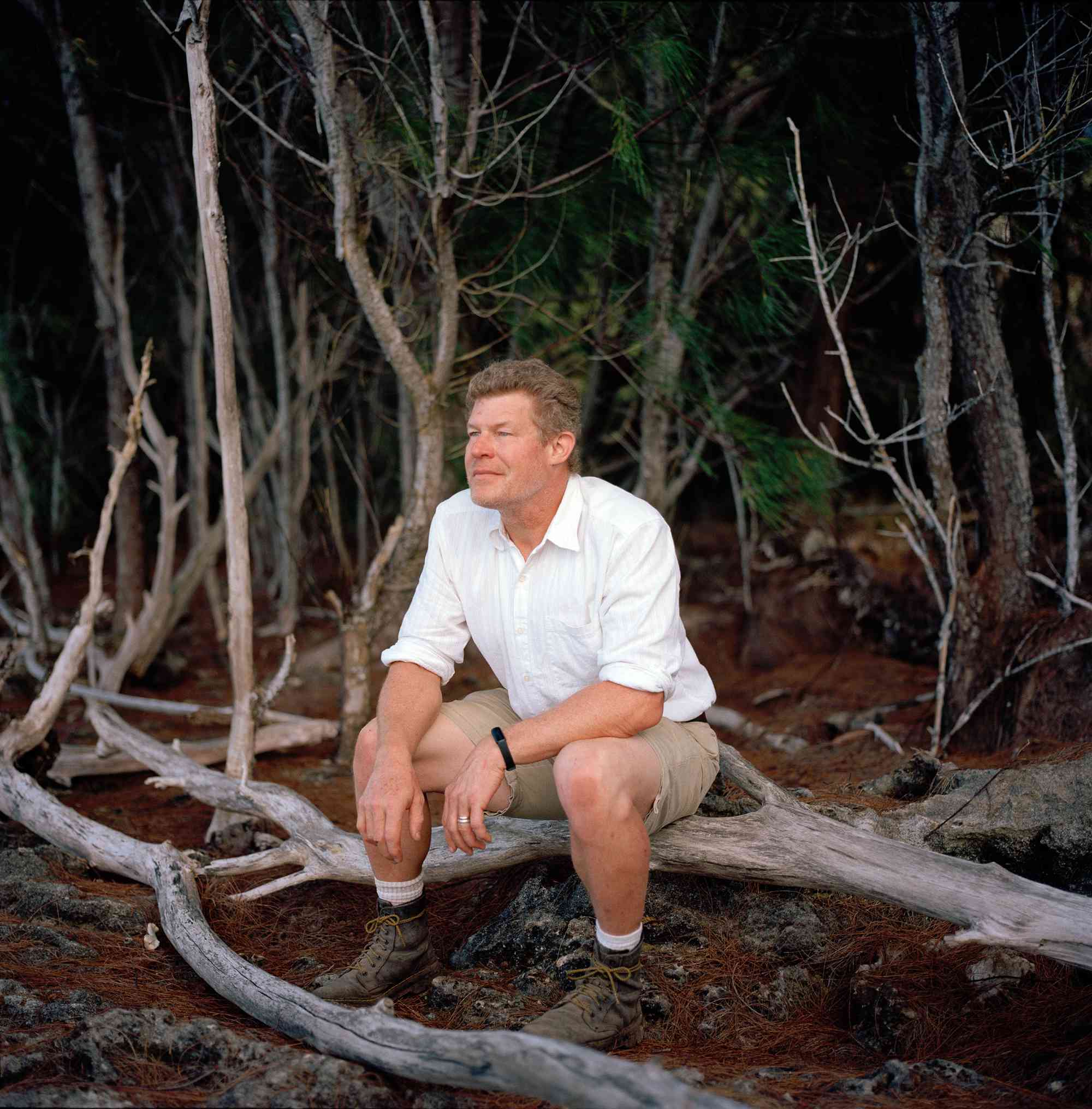

It’s not every day that a researcher finds himself at the center of a lavish 12-page magazine feature, replete with glossy photos of his sometimes place of work—a subtropical island. But that’s exactly what happened to Michael Jarvis, a professor of history at the University of Rochester and the director of the Smith’s Island Archaeology Project in Bermuda.

The Smithsonian Magazine’s cover story—“The Hidden History of Bermuda Is Reshaping the Way We Think of Colonial America”—chronicles how Jarvis has been working with Rochester students and local Bermudians over the past 14 years to excavate evidence of one of Britain’s first settlements in the Americas.

This past summer, the magazine sent a writer and a photographer to document the second of Jarvis’s National Endowment for the Humanities–funded excavations in a thick forest on one of Bermuda’s islands:

A few dozen yards away, in a dirty T-shirt, faded camo shorts and black work boots, Michael Jarvis hacked away at thick brush with a gas-powered saw. In this clearing on Smith’s Island, in Bermuda, Jarvis—“Chainsaw Mike” to his students—is unearthing one of the first New World towns built by English colonizers.

Established in 1612, just five years after the founding of the Jamestown colony in Virginia and eight years before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, the original colony on Smith’s Island was short lived—only to reemerge on another, nearby Bermudian island. But the mystery persists. “Its very existence was forgotten for four centuries; even its name remains unknown,” notes Andrew Lawler, who wrote the cover story for the Smithsonian.

Reading histories about the early beginnings of the American colonies—the traditional origin stories of the United States—one is hard pressed to find much, if any, mention of Bermuda.

“When historians have considered it, they usually dismiss it as a curiosity or a failure,” notes Jarvis, who sought to rectify that omission with his latest book, Isle of Devils, Isle of Saints (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022).

Yet, for a time, Bermuda was home to more settlers than either Virginia or Massachusetts, and far wealthier. Indeed, it was here that the English first grew tobacco and purchased enslaved Africans to work the fields, a practice that soon spread to American shores.

Rochester students and alumni on their Bermuda field experiences

Emily English ’27 (English Literature and History)

Emily English ’27 (English Literature and History)

New Bern, North Carolina

“Being a student whose main focus is in textual studies, going and experiencing the physical aspects of history was something I didn’t know I needed. Ever since going to Bermuda, I desire historical academics—not just as a backdrop to my studies in literature. Interacting with objects that hold history in ways I can’t comprehend with just research articles was simply mind blowing. It’s an opportunity to learn in ways that you can’t get from a classroom. Not only was the academic experience new and exciting, but the community I discovered and formed was one I will cherish forever.”

Skyler Frazier ’27 (Archaeology, Technology, and Historical Structures and Art History)

Skyler Frazier ’27 (Archaeology, Technology, and Historical Structures and Art History)

Tallahassee, Florida

“The opportunity to hold history in your hands isn’t one to pass by. Be prepared for hot days of physical labor but also beautiful seaside lunch breaks, and plenty of days off to experience these tropical islands filled with diverse cultures. I went to Bermuda in hopes of confirming my ambitions in archeology—it did exactly that. Due in large part to this experience with the Smith’s Island Archaeology Project (SIAP), I see myself continuing to pursue historical archaeology in academics and later as a career. The community of SIAP staff and the volunteers’ passion and enthusiasm for Bermudian history is absolutely infectious.”

Leigh Koszarsky ’14 (History and Anthropology)

Leigh Koszarsky ’14 (History and Anthropology)

Originally Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, now Charleston, South Carolina

“Initially I was a student with the field school in 2012 and 2013, then a site supervisor for several seasons. I would need to check my passport, but I think I’ve gone eight times in total. After my first field season I took on a history major, which gave me a lot more direction and focus in what I was looking for as a future career. It also gave me a start in database management and cartography—both skills that dominate my current job. Building upon my field school experiences, I went on to get my master’s in historical archaeology from UMass Boston and a graduate certificate in geographic information systems. I am currently a senior geographic information specialist at Brockington and Associates, an archaeology and historic architecture consulting firm in Charleston, South Carolina. There’s no way that I would be in this position today without the Bermuda field school experience.”

Ewan Shannon ’20 (Archaeology, Technology, and Historical Structures and Anthropology)

Ewan Shannon ’20 (Archaeology, Technology, and Historical Structures and Anthropology)

Staten Island, New York

“What I thought would just be ‘summer school’ turned into a love affair with Bermuda, historical archaeology, and Atlantic history—fundamental to everything else that followed in my academic tenure at the U of R, and beyond. It established for certain that historical archaeology was the path I wanted to follow and gave me a deep appreciation for interdisciplinary collaboration. Initially, I came on as a rising sophomore in 2017. Since then, [history professor] Mike Jarvis was kind enough to hire me as his field supervisor for the full season from May through early July. I’ve been in this role every summer since 2022. My time in Bermuda became a springboard to complete an MA in anthropology at The New School for Social Research in New York City, and I work now as an archaeologist for a cultural resource management company, Environmental Design & Research.”