What happens when an opera singer gets a cold?

Illness can threaten a performance, so singers rely on science, technique, and tough judgment calls.

When an instrument breaks, a musician can take it to a shop for a tune-up. But when your instrument is your body, there’s no quick repair—especially when a simple cold can throw your entire livelihood off-key.

“There’s a little panic and a prayer,” says Kathryn Cowdrick, a professor of voice with the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester and a veteran (mezzo soprano) opera singer who has performed at opera houses and with international companies across North America and Europe. Cowdrick, who began her career as a speech pathologist, knows the stakes are high when a cold strikes.

How do vocal cords work?

The mechanism itself is intricate: breath, vocal folds—also called vocal cords—and articulators are working together to create a voice uniquely our own. When a cold hits, the larynx becomes inflamed and the vocal folds swell.

“There’s a lot of mucus drainage that doesn’t allow our vocal folds to really be as efficient as they can be,” Cowdrick explains. With coughing, our breath—the power supply of the voice—is compromised, and, as a result, the vocal folds can’t come together gently and “become very vulnerable.”

How does the voice react to a cold?

An inflammation tends to lower the pitch range temporarily as the swollen vocal folds become thicker and vibrate more slowly. Swollen cords make it harder to access and sustain high notes without cracking or sounding strained.

For example, coloratura sopranos—who sing rapid, agile passages at the top of the vocal range—may have a particularly hard time because of decreased vocal flexibility.

But no matter the voice type—bass, tenor, alto, soprano—all react similarly to colds. Singers often lose pitch accuracy and brightness; they may sound breathy, weak, or less resonant. Low notes often lose depth or sound gravelly, while upper notes become harder to reach.

To adapt, singers might transpose pieces to a slightly lower key or choose to sing less-demanding arias if possible. But, Cowdrick notes, that’s simply not an option when performing with an orchestra: “You really need to sing what’s on the page.” That’s when it’s time for the cover—the understudy—to step in.

As long as singers are not too sick to perform, technique and vocal strategies come into play now. Focusing on breathing, if possible, and the support of the body’s lower core muscles can help.

“We find our position, we sing with that resonance, we know where to send our voice—but that sends us on a different path,” says Cowdrick. “That can be very disorienting for a singer.” With years of experience though, she says, one learns to balance the attempt at simply pushing through a performance—against protecting one’s own vocal longevity and health.

Somewhat oversimplified, she says, it’s the idea of “don’t push, sing carefully, and rest.”

Of course, other professional heavy voice users, such as teachers, sports coaches, clergy, and those in customer service also face vocal challenges and might benefit from speech therapy or voice study, she notes.

Must the show (really) go on?

Cowdrick doesn’t advocate for quick fixes or miracle cures. While there are plenty of helpful products, she cautions that if taken too long or incorrectly they can end up backfiring.

It’s crucial, she says, to seek medical guidance, regardless of whether it’s to help with allergies, coughs, colds, or the flu.

At the Eastman School of Music, all performers enjoy quick access—Cowdrick calls it “golden”—to dedicated medical care that specifically supports the needs of its artists through the Eastman Performing Arts Medicine Center (EPAM).

Yet, is it even worth performing while sick?

According to Glenn Schneider, an otolaryngologist at EPAM (whose specialty is treating larynx disorders, including voice disorders in singers and other professional voice users), there are clear risks. When vocal cords are swollen from a virus, the blood vessels under the surface of the vocal cords become dilated and prominent. With coughing, throat clearing, or voice overuse, he says, the blood vessels can rupture and cause vocal hemorrhage, which essentially means bleeding into the vocal cord. With voice rest and steroids most hemorrhages can resolve if caught early, Schneider says, but without proper treatment a hemorrhage can cause long-term scarring or vocal cord stiffening, which can be very difficult to treat.

Finding your voice at Eastman

What is it like to be a student at the world-renowned Eastman School of Music? From personal connections with professors to the chance to explore broader interests, discovery why Eastman is a top choice for so many students pursuing a career in music.

Maintaining your vocal cords

As both a teacher and seasoned performer, Cowdrick instills in her students the importance of prevention from the get-go. Healthy singing and singing with longevity involve cardiovascular health, sufficient hydration, vocal rest, warming up, and avoiding unnecessary talking on performance days.

“People who are in Broadway productions often sing a matinee and also an evening performance and spend the two or three hours in between in absolute silence,” Cowdrick notes. “This is how the body rejuvenates—with the silence, the hydration, and the rest.”

Her own pre-performance rituals, she says, include long walks, quiet afternoons, and vocal rest. “Sometimes I sit quietly in a library reading a book so that I’m not tempted to test my voice out all day long,” she says.

Of course, the best thing to do is to avoid catching a cold in the first place, advises Schneider, which may be easier said than done. How? He divides cold-fighting strategies into two buckets: prevention and preparation.

Prevention

- Drink 60–80 ounces of water daily to stay hydrated and to lubricate the vocal folds to allow them to vibrate easily.

- Sleep 7–9 hours every night.

- Exercise regularly.

- Eat a healthy diet and avoid eating late, or eating foods that can cause reflux symptoms such as acidic foods, fatty foods, or alcohol.

- Practice good hand-washing habits and wear a mask when around sick people.

Preparation

- Work with a vocal instructor to develop good vocal technique to help prevent injury, increase stamina for performances, and recover faster from illness.

- Don’t skip the warm-up and practice regularly to maintain your vocal instrument.

- Establish a relationship with either an otolaryngologist (or ideally a laryngologist) who has specialized training in voice disorders—so you have easier access to a medical resource when you get sick.

Bouncing back vocally from a cold

Start with a realistic assessment of your upcoming voice commitments, both speaking and singing, over the next 7 to 10 days—the average length of a cold, says Schneider.

“Whatever can be deferred or rescheduled should be considered,” he says, “to be able to perform your best and prevent vocal injury.”

If a commitment really cannot be changed, it’s worth checking in with your doctor. Schneider also suggests:

- No cutting corners on sleep and hydration.

- Over-the-counter pain medications are OK for aches and pains.

- For nasal congestion and cough, guaifenesin and dextromethorphan can be helpful to minimize symptoms. Avoid medications with pseudoephedrine and diphenhydramine as they can dry the vocal tract. Avoid Afrin (oxymetazoline) unless physician directed as it can lead to rebound nasal congestion.

- A longer lasting cough can be suppressed with dextromethorphan cough syrups or prescription Tessalon Perles.

- Nasal saline sprays or nasal irrigations (such as Navage or Neilmed sinus rinse) can help with nasal congestion and post-nasal drip.

- Personal or room humidifiers can be helpful.

- If the show must go on, reach out to your otolaryngologist or laryngologist to check if a laryngoscopy (a medical procedure to diagnose throat and voice-related issues) might be needed.

- In the most severe cases, a course of steroids like Prednisone or Medrol can be prescribed to reduce swelling.

Not the time for ‘bravado’

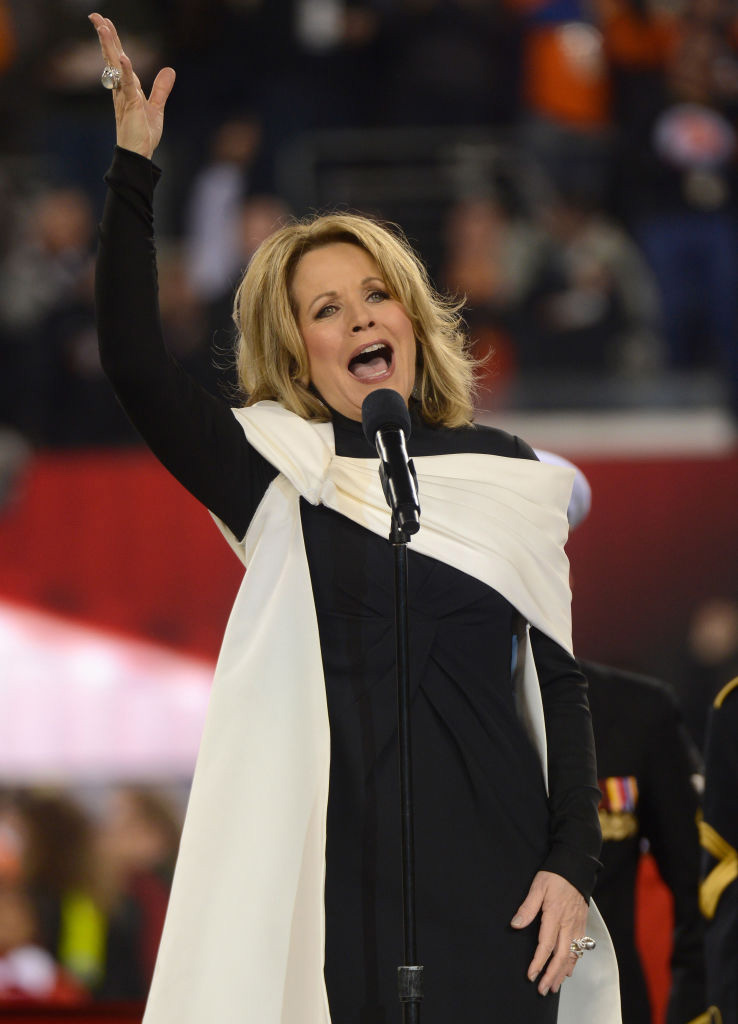

While germs can strike anyone, keeping your immune system strong and your body fit is paramount. That’s exactly what one of Eastman’s alumni does.

Star opera singer Renée Fleming engages regularly in Pilates exercises that focus on core strength, “which we singers need almost as much as dancers,” she told Classic FM.

Moderation is key.

“I try to live moderately, get enough sleep, eat and drink reasonably, and watch caffeine intake,” Fleming wrote in a 2013 Reddit forum in response to fan questions about protecting her voice throughout her long career. “The most important thing is choosing repertoire wisely—not too heavy, and the appropriate tessitura—not too high or low in terms of mean pitch, [and to] keep singing and stay[ing] in vocal shape. Keep the voice moving—it’s not easy.”

For singers, of course, the instrument isn’t a violin or a piano—but their body.

And when that body catches a cold, the right response really “isn’t bravado,” says Cowdrick.

Instead, experts agree, it’s time to focus on rest and recovery, and to respect the human voice with its innate fragility.

Tips and tricks from Eastman School of Music experts

Joshua Conyers, a Grammy-nominated baritone and Eastman assistant professor of voice, has performed with the most prestigious opera companies, symphonies, and concert halls in the world, including the Metropolitan Opera (New York), Lyric Opera of Chicago, Seattle Opera, Washington National Opera, English National Opera, and Carnegie Hall (New York).

“My first priority is rest—both vocal and physical. I hydrate constantly with room temperature water, herbal teas, broths, use steam inhalation to soothe my throat, and do nasal rinses to clear out congestion. I avoid speaking unless absolutely necessary and communicate through writing or text. If singing is unavoidable, I warm up very gently, sing only as much as needed, and adjust phrasing or dynamics to protect my voice while still delivering musically. If my symptoms worsen, I’ll seek out my ENT for a consultation.”

Kiera Duffy, a soprano and associate professor of voice, has performed as a soloist with many of the world’s preeminent classical music organizations, among them the Metropolitan Opera, Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, London Symphony, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Ungaku-juku (Japan).

Kiera Duffy, a soprano and associate professor of voice, has performed as a soloist with many of the world’s preeminent classical music organizations, among them the Metropolitan Opera, Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, London Symphony, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Ungaku-juku (Japan).

“I do something perhaps a bit counterintuitive—I exercise. Of course, if I’m experiencing chesty cough symptoms or am feeling ‘flu-y,’ I skip the gym and take the usual rest and hydration route. But, if I’m feeling the dreaded little tickle in the throat or the extra sniffle, I try to nip things in the bud with moderate exercise. Vigorous walking for 30 minutes and lighter weight training, for example, are a great way to boost immunity and calm the body’s inflammatory response. I also double down on good nutrition, such as leafy greens and protein, avoiding sugars and processed foods. I also prioritize 8 hours of nightly sleep, good hydration, and stress reduction, which is admittedly hard when doing your job depends on your not getting sick. At the end of the day, I am only human and if I am too ill to sing, it’s okay sometimes to surrender.”

Anthony Griffey, a professor of voice and four-time Grammy Award–winning tenor, has performed leading roles among others at the Metropolitan Opera, Opéra National de Paris, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Opera Australia, and the Glyndebourne Festival in England.

Anthony Griffey, a professor of voice and four-time Grammy Award–winning tenor, has performed leading roles among others at the Metropolitan Opera, Opéra National de Paris, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Opera Australia, and the Glyndebourne Festival in England.

“Don’t panic! Your mental health is probably the most important thing to consider during this time. Rest. Don’t keep ‘checking’ to see if your voice is there. Hydrate, steam, and eat something. Remind yourself that you have a technique and the ability to control what your voice needs to do. Use this as an opportunity to familiarize yourself with different physical sensations. There will be times in your career, not only due to illness, where singing might feel different because of environmental factors, or jet lag and it’s paramount for a professional singer to be adaptable.”

Nicole Cabell, a soprano and associate professor of voice, was named 2005 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World. She has performed at the most prestigious operas and concert halls in the world, among them the Royal Opera House (Covent Garden, London), Metropolitan Opera, Teatro Colòn de Buenos Aires, Deutsche Oper Berlin, and the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Nicole Cabell, a soprano and associate professor of voice, was named 2005 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World. She has performed at the most prestigious operas and concert halls in the world, among them the Royal Opera House (Covent Garden, London), Metropolitan Opera, Teatro Colòn de Buenos Aires, Deutsche Oper Berlin, and the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

“The first thing I do is rest. I try to get an abundance of sleep. Then I’ll take an anti-inflammatory supplement like Bromelain or Quercetin to bring down the swelling. Most importantly I will lean on the technique I’ve learned over these decades to sing as slim and efficient as possible, warming up with humming or semi-occluded vocal exercises that access the thin edges of the vocal cords.”