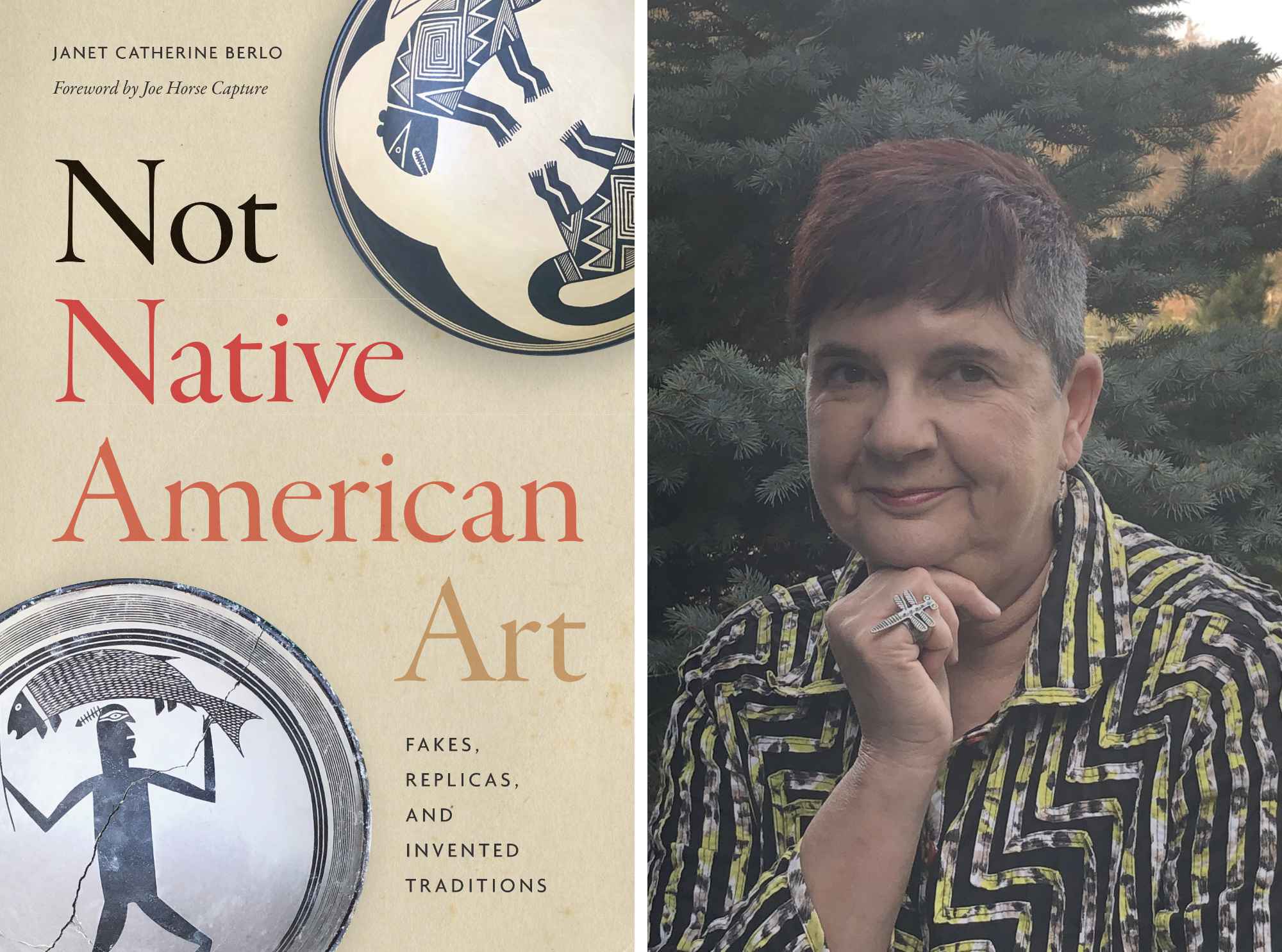

A Rochester art historian on the proliferation of indigenous fakes and replicas—and the blurry line between appropriation and admiration.

Janet Berlo knows a thing or two about fakes. For starters, they can be hard to spot.

“Many things would fool me. I can’t be an expert on the art works of scores of Native nations,” admits Berlo, a professor emerita in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Rochester. But a Northwest Coast Native mask made in Indonesia? “Well, that’s relatively easy.”

As the commercial value of Native American art has increased dramatically over the last decades, so has its forgery.

At one point, a top international auction house approached Berlo, an expert on Native American art and visual culture, for her opinion on a notebook of complex 19th-century Native American pencil drawings. There was just one small problem.

Berlo knew it was a fake. She was also convinced that the late Mexican caricaturist, Miguel Covarrubias, in whose estate the notebook was discovered, had never meant for it to be sold as authentic but had merely entertained himself by making his own version of Native art.

An “accidental fake,” as Berlo calls it.

The auction house Sotheby’s, meanwhile, thanked her politely and then contacted other experts. Curators at the Smithsonian Institution agreed with Berlo’s assessment. Eventually some non-academic, a known collector, spun a whole fantasy around the notebook. And up it went for auction as the real McCoy.

“Anybody in art history who deals with major auction houses gets disillusioned very quickly,” Berlo says.

Of course, forgery and mimicry aren’t new phenomena. Renaissance artists regularly imitated classical originals. Take for example Sandro Botticelli’s famous Birth of Venus, in which the goddess covers her nakedness with her hands. That particular pose—cribbed from classical sources—was so widely copied in the Renaissance that it had its own name, “Venus pudica.”

Following decades of research and interviews with curators, collectors, restorers, Native artists, and replica makers, Berlo has traced the historical and social contexts of forgeries, imitations, replications, and appropriations by both Native and non-Native makers. The result is her newest book, Not Native American Art: Fakes, Replicas, and Invented Traditions (University of Washington Press, 2023).

What is ‘real’ Native American art?

“An excellent question,” says Berlo with a sigh. Recently, the FBI called to ask if she could lead a Zoom conference for a group of special agents. She told them they’d be disappointed.

Those hoping for hard-and-fast rules won’t get them from Berlo, who says she’s not interested in being able to declare authoritatively, “This is how you tell which one is fake. And, no, real moosehide doesn’t feel like this.” Instead, she’s digging into the bigger cultural issues.

Her book is an invitation to ponder the tangled history of Native art. Thoughtful and nuanced in her writing, Berlo seeks answers in the gray areas, acknowledging that what constitutes “genuine” versus “fake” when it comes to Native American identity and Native objects is often not clearcut.

Honored by the Native American Art Studies Association in 2023 with its lifetime achievement award, Berlo says she tried to show that “something that seems very simple, is in reality complex and complicated, not something to make a snap judgment about.”

After a more than four-decades-long career in art history, she wrote her latest book also in the hopes that younger generations of scholars won’t rush to immediate judgment and condemn automatically “as cultural appropriation” when non-Native people are involved in creating Native-style art.

The paradox of ‘authentic replicas’

Replica-making by non-Natives, Berlo points out, can entail painstaking training with Native crafts people, researching tribal histories, becoming expert in various techniques, and attempting to ensure the preservation of knowledge and traditions.

She tells the story of Paul and Laurel Thornburg, non-Natives who make “authentic replicas” from scratch. The Arizona couple has experimented with various aspects of making so-called Mimbres pottery—specifically, the pre-historic ceramic clay bowls featuring decorations of geometric patterns and natural life that were produced by the indigenous peoples of the Mimbres Valley in New Mexico about a thousand years ago.

Every aspect of the couple’s craft conforms as closely as possible to ancient Mimbres-making practice, Berlo observed—from finding the right white clay, to firing bowls in open pits, to assessing the advantages of oak over cottonwood as fuel. Their experimentations, instructions, and results of nearly 40 years of reproducing Native pottery are carefully recorded in photos and notes that the couple intends to donate to the Arizona State Museum.

That begs the question—is Native art automatically a forgery if it’s made by a non-Native artist, even if it conforms to all the original procedures? Is careful reproduction a kind of illegitimate appropriation? Opinions differ widely, often depending on age.

“For many of my colleagues under 40, it’s cut and dry: You’re either Native or non-Native. It’s either right or it’s wrong,” she says. “But life is not that simple.”

And then there’s the issue of Native artists’ making replicas themselves. Is that considered forgery, too?

Take, for instance, the example of the Seneca people of western New York who replicated their ancestral arts during the Great Depression, under the auspices of the 1935 Works Progress Administration, a government employment and infrastructure program created by President Franklin Roosevelt.

“The impetus may be principally economic, and arise from outside the community,” Berlo writes, acknowledging that “aesthetic pride in the work of ancestors is not incompatible with a desire to earn a living through one’s art.”

Of course, borrowing ideas and using techniques from other cultures is nothing new. “If people only knew history, says the pedantic scholar in me, they would see that these actions are so old, and happen all around the world,” says Berlo, who has authored, coauthored, and coedited a dozen books, including four textbooks and a memoir, Quilting Lessons: Notes from the Scrap Bag of a Writer and Quilter (Bison Books, 2001). Hardly anybody would argue colonialism didn’t involve stealing and usurping. “I’m not saying, ‘Oh, that’s good.’ But it’s always been that way,” she notes.

Native American arts have long been enlivened by outside influences and additions. “Everyone thinks of beadwork, when they think of Native American art,” she says. But beads were introduced from Venice more than 200 years ago. “No one would say that beads are now not ‘traditional’ in Native art.”

The spectrum from admiration to appropriation

While cultural sensitivities have evolved over the last two decades, leading to greater awareness of cultural appropriation or misappropriation (such as reducing Native culture to a Halloween costume or party theme), gray areas nonetheless persist.

Tracing the long history of non-Natives “playing Indian” and replicating Native American art comes with a whole host of underlying motivations, many of which have no harmful intentions but, rather, are signs of admiration, Berlo contends. Often the answer lies in the eye of the beholder.

“The long-standing Anglo-American desire to recall and embody a mythic Native past is a troubling one, rooted in a deeply violent and racist past, as anyone with a cursory knowledge of American history recognizes,” Berlo writes in her chapter “Cultural Cross-Dressers: A Long History of Imitating Indians.” Describing her visits to non-Native groups who engage in various reenactments of either fictional or historic Native events, Berlo discovered that while some of the participants “did have romanticized ideas,” many more demonstrated “so much knowledge and respect.”

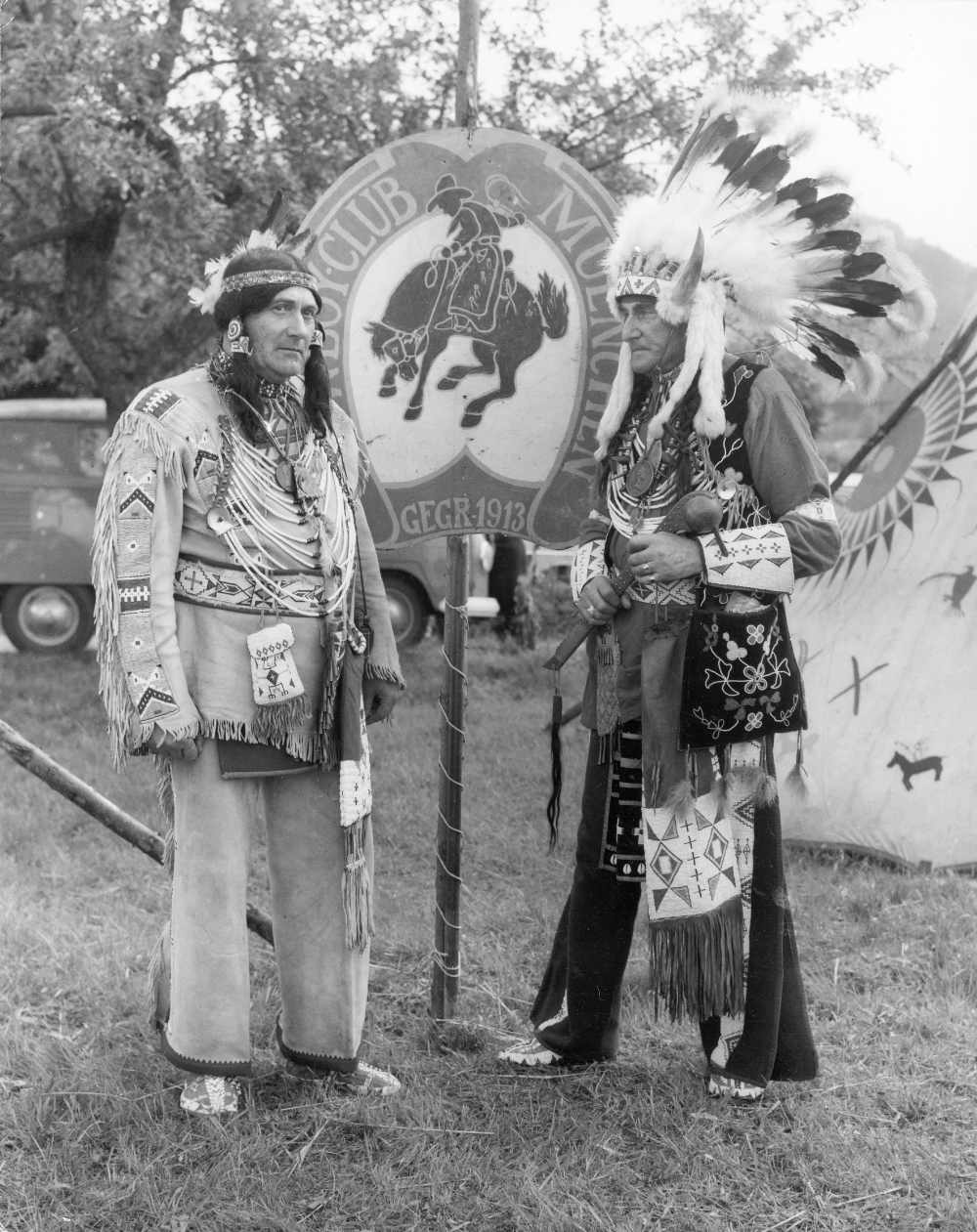

The role-playing phenomenon is not limited to America. Germans, Berlo notes, love imitating a romanticized version of Native Americans, a tradition that predates even the (often inaccurate) adventure tales of widely read German author Karl May (1842–1912). According to Berlo, many Germans have been fascinated by North American Indians since the first translation of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales nearly 200 years ago. Today, one would be hard-pressed to find a German who doesn’t know the dashing Apache chief Winnetou and his white “blood brother” Old Shatterhand, May’s most famous fictional characters.

Since the early 1990s, the German town of Radebeul (May’s last residence) has hosted an annual outdoor festival during which locals, dressed in pseudo-Native garb, participate as extras in the reenactments of the author’s famous stories. An even larger, live outdoor drama, the Karl-May Spiele in Bad Segeberg, has been running “Indian” theater performances every summer for the past 70 years.

Lakota artist and scholar Arthur Amiotte, one of Berlo’s friends and past coauthors, has worked as a consultant for the Karl May Museum. “He’s very relaxed about all of this,” Berlo says.

At one point, her research took an unexpected turn.

In coastal British Columbia, Canada, Berlo met a Native American who admitted to buying “Indian” quilled bags, used by his family for ceremonial dances, from “a white guy.”

“It’s a cosmopolitan world,” she says. “There’s no one-size-fits-all if you really take seriously the fact that Native cultures have interacted with so many forces in culture and history over the past 500 years.”

In April 2024, Confluences: A Celebration of Janet Berlo was held at Rochester to recognize Berlo’s contributions to the discipline. Visit the conference website for essays, reflections, and audio from the event.