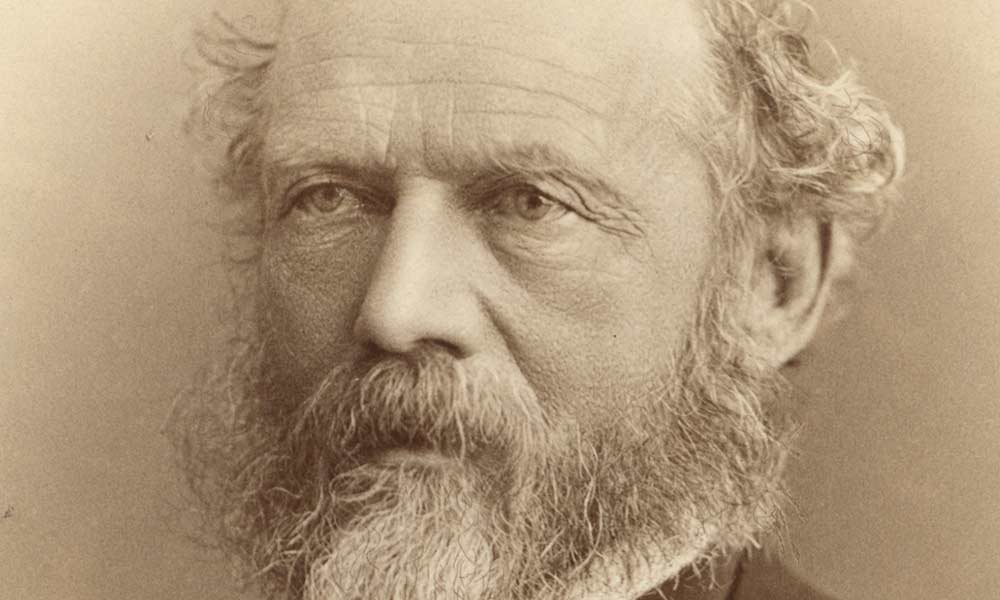

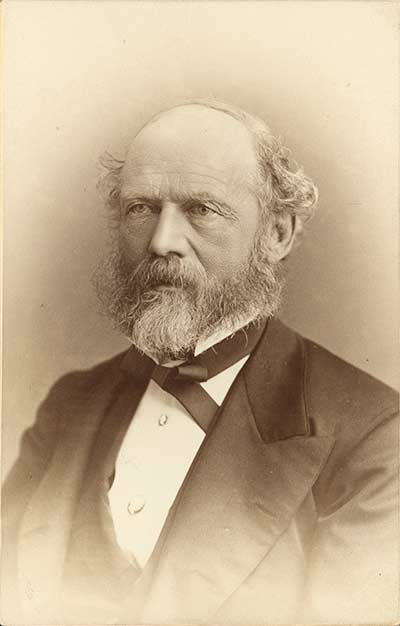

He studied Native American cultures, researched beaver colonies, corresponded with Charles Darwin, served in the New York State Legislature, and influenced the likes of Karl Marx. And, in his role as an attorney, he helped secure the charter for the University of Rochester.

“Lewis Henry Morgan was a scholar with broad interests, working on—and writing about—all kinds of things,” says Robert Foster, professor of anthropology at Rochester. “But for a variety of reasons, he has been remembered selectively or forgotten altogether.”

With this as the bicentennial year of Morgan’s birth—and the University’s Rush Rhees Library the principal repository for artifacts and materials related to Morgan—Foster thought it was time to take a fresh look at his legacy. Thanks to a $30,000 grant from the University’s Humanities Project, along with $3,000 from his own research budget as Richard L. Turner Professor of Humanities, Foster launched the Lewis Henry Morgan at 200 multi-partner initiative to acquaint people with Morgan’s life and work, as well as offer a critical reevaluation. The centerpiece is an online digital project that documents Morgan’s work, provides a biographical overview, and summarizes the many events and activities taking place throughout the region.

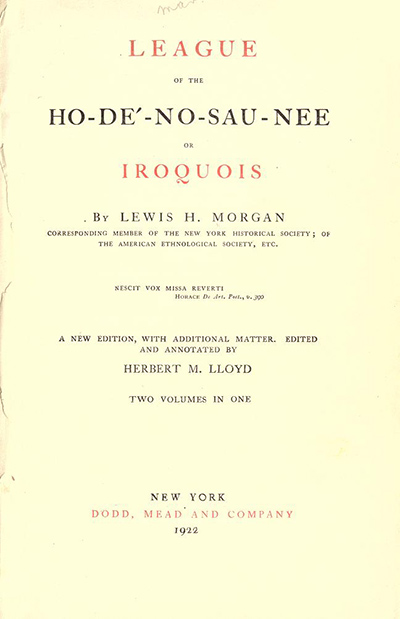

Morgan’s League of the Ho-de’-no-sau-nee (or Iroquois), published in 1851, became a seminal work, often considered to mark the beginning of American anthropology.

“Morgan tried to avoid the trap of understanding other cultures in terms of his own. He learned that the social and political world of the Haudenosaunee was organized, systematic, and logical, but not on terms that were familiar to Europeans,” says Foster. “That was a fundamental anthropological insight—engage other people on terms that you don’t simply reject out-of-hand as being irrational, unintelligible, or wrong.”

Morgan’s own copy of League of the Ho-de’-no-sau-nee is on display at Rush Rhees Library as part of the Lewis Henry Morgan at 200 exhibition, with companion displays at the Central Library of Rochester and the Rochester Museum and Science Center.

Among the scholars who have drawn from the library’s rich Lewis Henry Morgan collection is Daniel Noah Moses ’01 (PhD), whose book, The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan (University of Missouri Press, 2009), is based on his doctoral dissertation in history at Rochester. According to Moses, Morgan should be remembered for his role in developing a big-picture story of human civilizations now widely taken for granted.

“With his deep respect for the power of the human mind, Morgan focused on the human interaction with the environment, the interplay of technological innovation, the development of material culture, and changes in family, property, and social arrangements to trace the human story from the most primitive conditions to the complex state-based societies of his day,” says Moses.

For Moses, Morgan’s account of social evolution helped strengthen the concept of the “social,” in contrast to what might be “natural” or “transcendent.” How much of what individuals take as “natural” is a product of what is imposed upon them by the society and time into which they are accidentally born? “Morgan deserves a great deal of credit for his pioneering anthropological attempts to understand what accounts for the range of human social diversity, how societies hold together, and how they change,” says Moses.

Despite his accomplishments, Foster explains that Morgan did not fully rid himself of the prejudices and assumptions of the 19th-century society he inhabited. Believing that Native Americans would vanish through assimilation, he sought to record their way of life before it all disappeared. And, as explained in his book Ancient Society, Morgan firmly believed that while all societies evolved from a rude to a civilized state—specifically progressing from savagery to barbarism to civilization—they did not all progress at the same rate.

At the same time, Foster calls Morgan’s contributions “incontestable,” citing his work on kinship terminology. “He basically put kinship studies on the map as a central anthropological preoccupation,” says Foster. “His project of documenting kin terminologies from around the world is an extraordinary example of a big data project in the 19th century. To him we owe the discovery that there are only a handful of types of kin terminologies—the terms by which people address and refer to their relatives.”

For Melissa Mead, the John M. and Barbara Keil University Archivist and Rochester Collections Librarian, one of the highlights of the library exhibit is Morgan’s own copy of League of the Ho-de’-no-sau-nee, which has handwritten annotations. “He changed words and phrases, such as Indian race to tribe or nation,” says Mead. “To me, that demonstrates a constant evolution in his thinking, and reinforces the need to take people’s writings on their terms, and not read them with a modern-day sensibility.”

Morgan was also among the first—if not the first—to collect artifacts in an academically significant way. Not wanting to simply display exotic masks and headdresses as mere curiosities, Morgan collected everyday items of material culture such as tools and clothing. He tried to obtain the correct vernacular terms for each item and the circumstances under which it was used. “His work on material culture was quite original,” says Foster. “I can’t think of another collection before his that had greater breadth and better documentation.”

A true polymath, Morgan studied more than human societies, as evidenced by his 1868 book The American Beaver and his Works. “Up until then, animal studies were based on anatomy,” says Foster. “In many ways, Morgan’s book was the first account of animal behavior observed ‘in the wild’.”

While Morgan was very much a creature of the 19th century, some of his insights presaged attitudes more prevalent in the 20th and 21st centuries. When it came to intelligence, Morgan made no qualitative distinction between humans and animals, believing both could improve their conditions and progress. And he ended American Beaver with a series of provocative insights, questioning whether it is ethical to eat animals. “An arrest of the progress of the human race can alone prevent the dismemberment and destruction of a large portion of the animal kingdom,” he wrote.

Morgan never taught in a classroom, having done his work long before colleges and universities developed areas of specialization. But after becoming president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he did establish a section in the organization for anthropology.

Along with the online project and exhibitions on and off campus, Lewis Henry Morgan at 200 has included events on contemporary Haudenosaunee issues in collaboration with the Tonawanda Reservation Historical Society, the Seneca Art and Culture Center at Ganondagan, and the Rochester Museum & Science Center. In addition, a walking tour has been developed for Friends of Mt. Hope Cemetery, which includes the Morgan family mausoleum and the graves of some members of the Pundit Club, a literary fraternity co-founded by Morgan.