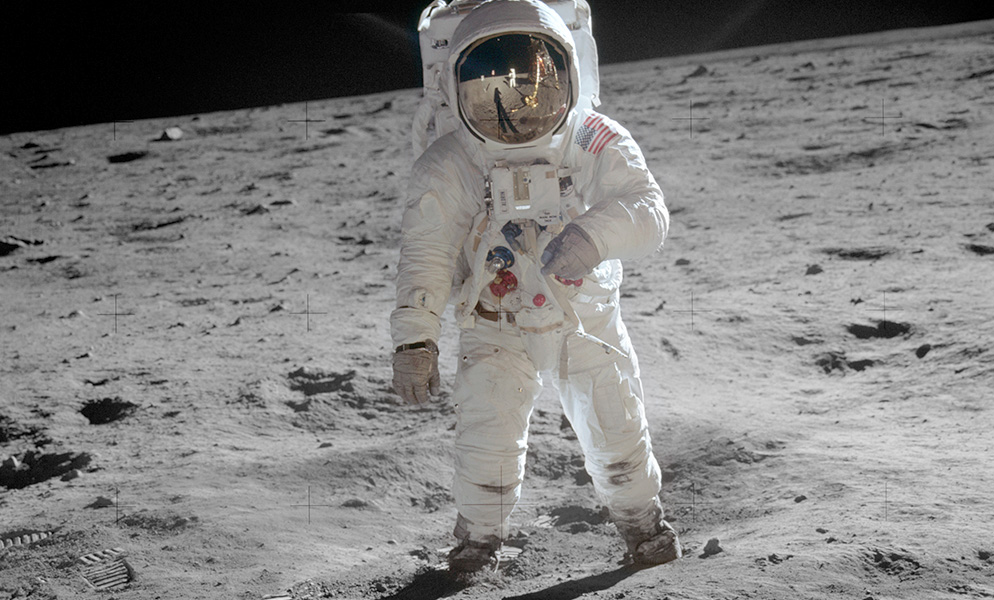

July 20, 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of NASA’s Apollo 11 moon landing. On this day in 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the first steps on the moon’s surface, collecting lunar rocks and bringing them back to Earth. The samples they gathered still inform research today, including research conducted by Miki Nakajima, an assistant professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester.

Nakajima studies the formation and evolution of the Earth, the moon, and other planetary bodies in the solar and extrasolar systems. Here, she reflects on the anniversary of the moon landing and how the Apollo missions have impacted her work.

Apollo astronauts’ back-up plans included a head butt

When Duncan Moore, Rochester professor of optical engineering, met the Apollo 11 astronauts during 30th anniversary celebrations in 1999 he had to ask: What would you have done if your radios failed during the historic moon walk?

How has the moon landing 50 years ago impacted research today?

The lunar rocks brought back by the Apollo missions completely changed our views of the moon. Before the missions, there were several hypotheses to explain the moon’s origin but none of them were very successful. After analyzing the lunar rocks gathered by the Apollo missions, scientists found that these rocks were strikingly similar to rocks that make up Earth. This led to the hypothesis that Earth and the moon both formed by a large impact, which could have homogenized the two bodies. This impact hypothesis has been widely accepted, but the details are highly debated. For example, what was the size of the impactor, and what was the impact velocity? What was the spin state of the Earth before the impact? There are other things to consider besides the isotopic similarity, including the Earth-moon angular momentum, the mass of the moon, the state of the Earth’s mantle after the impact. In my opinion, none of the models have explained all the constraints we have.

What are some of your current projects to study Earth’s moon?

My lab is investigating the essential conditions needed to form the moon via an impact. This research will help support or eliminate some of the proposed impact hypotheses. Moreover, we are answering questions including whether the impact helped generate an early magnetic field and how much volatiles (chemical elements including carbon, hydrogen, and sulfur) have escaped from the Earth, both of which contributed to generating a habitable environment on Earth. I conduct numerical simulations to reproduce the state of the Earth and moon during and after the impact to explain constraints that originate from the Apollo rock samples, chemistry, geochemical observations, and other computer models.

What is next for lunar research?

It still strikes me that we sent humans to the moon 50 years ago when our computational capability was much more limited than today. I am very excited that there are so many ongoing and future missions to go back to the moon again with the latest equipment, which will revolutionize our understanding of the history of the Earth, moon, and the solar system. My personal interest is in understanding how planets form and evolve and then making future predictions to really identify the history of planets. Also, by looking at the planets, the moons, and the solar and extrasolar systems, we can better understand the conditions needed to make a planet habitable.