Using new data gathered from sites in southern Africa, University of Rochester researchers have extended their record of Earth’s magnetic field back thousands of years to the first millennium.

The record provides historical context to help explain recent, ongoing changes in the magnetic field, most prominently in an area in the Southern Hemisphere known as the South Atlantic Anomaly.

“We’ve known for quite some time that the magnetic field has been changing, but we didn’t really know if this was unusual for this region on a longer timescale, or whether it was normal,” says Vincent Hare, who recently completed a postdoctoral associate appointment in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (EES) at the University of Rochester, and is lead author of a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters addressing changes in the earth’s magnetic field.

Weakening magnetic field a recurrent anomaly

The new data also provides more evidence that a region in southern Africa may play a unique role in magnetic pole reversals.

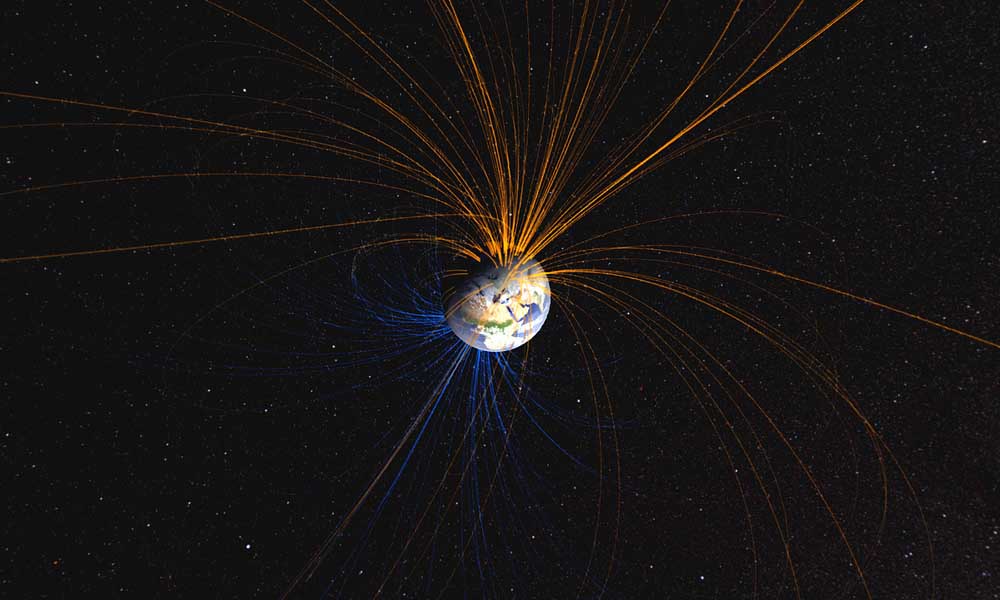

The magnetic field that surrounds Earth not only dictates whether a compass needle points north or south, but also protects the planet from harmful radiation from space. Nearly 800,000 years ago, the poles were switched: north pointed south and vice versa. The poles have never completely reversed since, but for the past 160 years, the strength of the magnetic field has been decreasing at an alarming rate. The region where it is weakest, and continuing to weaken, is a large area stretching from Chile to Zimbabwe called the South Atlantic Anomaly.

In order to put these relatively recent changes into historical perspective, Rochester researchers—led by John Tarduno, a professor and chair of EES—gathered data from sites in southern Africa, which is within the South Atlantic Anomaly, to compile a record of Earth’s magnetic field strength over many centuries. Data previously collected by Tarduno and Rory Cottrell, an EES research scientist, together with theoretical models developed by Eric Blackman, a professor of physics and astronomy at Rochester, suggest the core region beneath southern Africa may be the birthplace of recent and future pole reversals.

“We were looking for recurrent behavior of anomalies because we think that’s what is happening today and causing the South Atlantic Anomaly,” Tarduno says. “We found evidence that these anomalies have happened in the past, and this helps us contextualize the current changes in the magnetic field.”

The researchers discovered that the magnetic field in the region fluctuated from 400-450 AD, from 700-750 AD, and again from 1225-1550 AD. This South Atlantic Anomaly, therefore, is the most recent display of a recurring phenomenon in Earth’s core beneath Africa that then affects the entire globe.

“We’re getting stronger evidence that there’s something unusual about the core-mantel boundary under Africa that could be having an important impact on the global magnetic field,” Tarduno says.

A pole reversal? Not yet, say researchers.

The magnetic field is generated by swirling, liquid iron in Earth’s outer core. It is here, roughly 1800 miles beneath the African continent, that a special feature exists. Seismological data has revealed a denser region deep beneath southern Africa called the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province. The region is located right above the boundary between the hot liquid outer core and the stiffer, cooler mantle. Sitting on top of the liquid outer core, it may sink slightly, disturbing the flow of iron and ultimately affecting Earth’s magnetic field.

A major change in the magnetic field would have wide-reaching ramifications; the magnetic field stimulates currents in anything with long wires, including the electrical grid. Changes in the magnetic field could therefore cause electrical grid failures, navigation system malfunctions, and satellite breakdowns. A weakening of the magnetic field might also mean more harmful radiation reaches Earth—and trigger an increase in the incidence of skin cancer.

Hare and Tarduno warn, however, that their data does not necessarily portend a complete pole reversal.

“We now know this unusual behavior has occurred at least a couple of times before the past 160 years, and is part of a bigger long-term pattern,” Hare says. “However, it’s simply too early to say for certain whether this behavior will lead to a full pole reversal.”

Even if a complete pole reversal is not in the near future, however, the weakening of the magnetic field strength is intriguing to scientists, Tarduno says. “The possibility of a continued decay in the strength of the magnetic field is a societal concern that merits continued study and monitoring.”

This study was funded by the US National Science Foundation.

In the Field: “Archaeomagnetism” at work

The researchers gathered data for this project from an unlikely source: ancient clay remnants from southern Africa dating back to the early and late Iron Ages. As part of a field called “archaeomagnetism,” geophysicists team up with archaeologists to study the past magnetic field.

The Rochester team, which included several undergraduate students, collaborated with archaeologist Thomas Huffman of the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, a leading expert on Iron Age southern Africa. The group excavated clay samples from a site in the Limpopo River Valley, which borders Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Botswana.

During the Iron Age in southern Africa, around the time of the first millennium, there was a group of Bantu-speaking people who cultivated grain and lived in villages composed of grain bins, huts, and cattle enclosures. Droughts were devastating to their agriculturally based culture. During periods of drought, they would perform elaborate ritual cleansings of the villages by burning down the huts and grain bins.

“When you burn clay at very high temperatures, you actually stabilize the magnetic minerals, and when they cool from these very high temperatures, they lock in a record of the earth’s magnetic field,” Tarduno says.

Researchers excavate the samples, orient them in the field, and bring them back to the lab to conduct measurements using magnetometers. In this way, they are able to use the samples to compile a record of Earth’s magnetic field in the past.