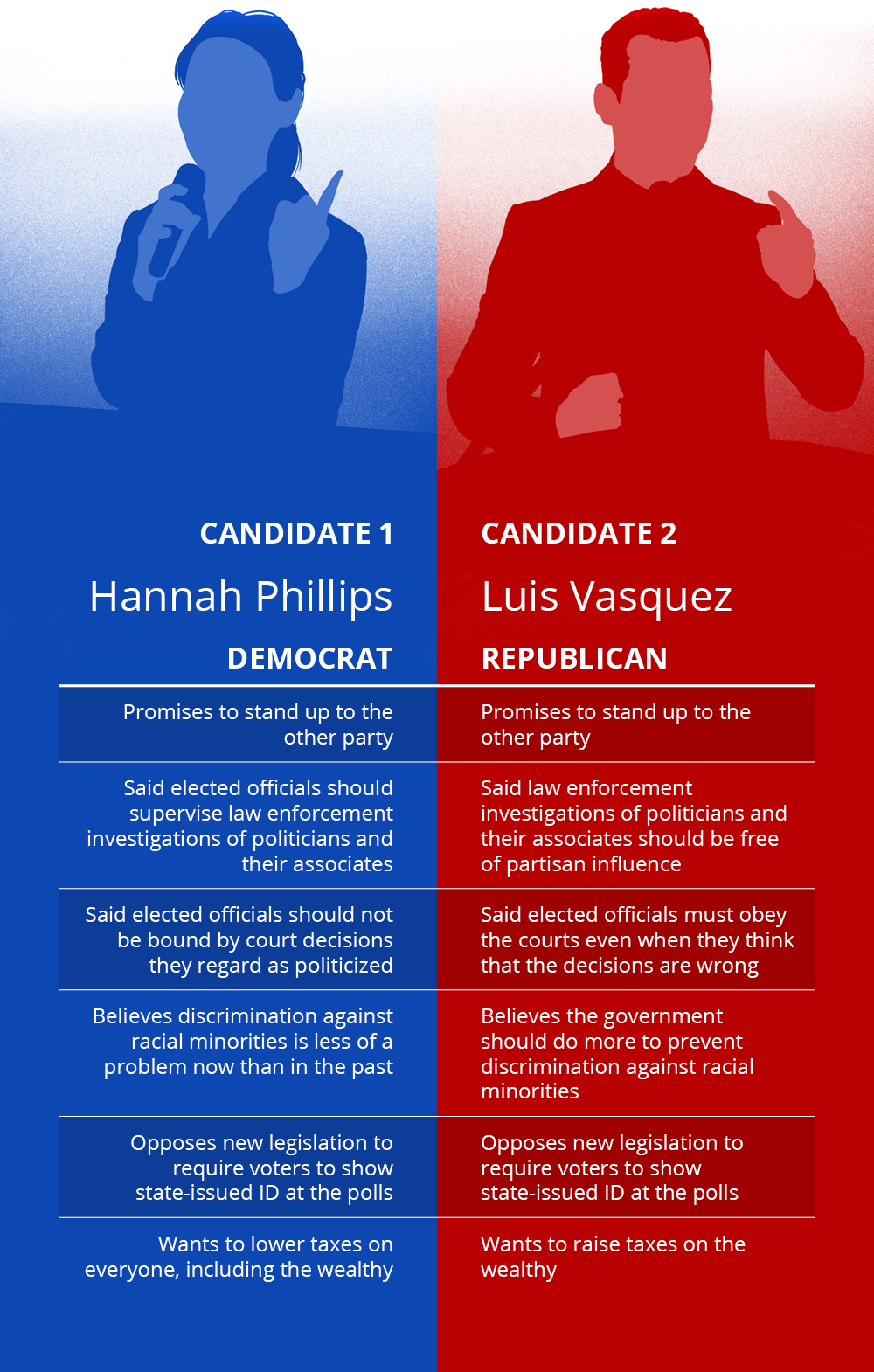

Imagine you are a fairly mainstream Republican voter and are considering Republican candidate Luis Vasquez. He says he wants to raise taxes on the wealthy and believes government should do more to prevent discrimination against racial minorities. Would you still vote for him?

What if you are a lifelong Democrat? Would you vote for Democratic candidate Hannah Phillips, who wants to lower taxes on everyone, including the wealthy? What if Phillips also espouses views that run counter to established democratic norms and rules, declaring, for instance, that “elected officials should not be bound by court decisions they regard as politicized.”

Hannah Phillips and Luis Vasquez are fictive candidates in an experiment conducted by Bright Line Watch, a group of political scientists, among them Gretchen Helmke, professor of political science at the University of Rochester, and Mitchell Sanders ’97 (PhD) of Meliora Research, who monitor US democratic practices and potential threats.

Bright Line Watch based its selection of policy questions for the experiment on a recent paper by Vanderbilt University’s Larry Bartels, who studies American voters and public opinion, and who found that questions about taxation policy and racial discrimination generate the biggest partisan divides among the US electorate.

The Bright Line Watch team sampled nearly 1,000 online participants, weighted to approximate a representative sample of the US population: 35 percent of respondents identified as Republicans or Republican-leaning, 43 percent as Democrats or Democratic-leaning, and 17 percent as independents who did not lean toward either party.

Each respondent was asked to choose between a pair of hypothetical candidates in an upcoming election. Each candidate was described using eight characteristics: name, party preference, positions on policies toward taxation and racial discrimination, and four positions on democratic values and norms. All characteristics were randomly generated, and at times at direct odds with what most voters would expect from a mainstream Democratic or Republican candidate. Some of the fictive candidates’ views and positions were undemocratic.

Why? Building on the pioneering work done by Yale political scientists Matthew Graham and Milan Svolik, the Bright Line Watch team wanted to test how committed the American public really is to its democracy. Are there universal democratic principles that, if violated by politicians, would generate resistance from the public, and would citizens of all political stripes be equally willing to punish candidates for such violations?

The team’s finding is striking: partisanship outweighs all other factors for both Republicans and Democrats. In other words, a die-hard Democrat is still more likely to vote for the fictive Democratic candidate although she espouses policies and views that are either typically Republican (lowering taxes) or outright undemocratic (elected officials should supervise law enforcement investigations of politicians and their associates). The same holds true for Republican-leaning voters.

Bright Line Watch also found that all participants value democratic norms related to judicial independence, neutral investigations, and political compromise, but Democrats and Republicans strongly disagree when it comes to questions of voting rights and equal access.

The Bright Line team—the political scientists John Carey and Katherine Clayton at Dartmouth College, Brendan Nyhan at the University of Michigan, and Susan Stokes at the University of Chicago, together with Rochester’s Helmke and Meliora Research’s Sanders—focused their survey “Party, Policy, Democracy and Candidate Choice in U.S. Elections” on the attitudes of ordinary US voters.

Bernard Avishai, a visiting professor of government at Dartmouth (and an adjunct professor of business at Hebrew University in Israel), is a colleague of Carey and Clayton’s. He wrote about the Bright Line Watch study in depth in a recent piece for The New Yorker.

As Avishai put it succinctly: “The good news for the Republic is that voters of all party affiliations care about judicial independence. The bad news is that Democrats and Republicans diverge dramatically on the question of access to the polls.”

“Our results on voter ID laws particularly underscore the partisan divide among voters,” confirms Rochester’s Helmke.

“The polarized response to these policies illustrates how partisans can become deeply split over which democratic priorities are worth protecting,” writes the team.

Here are Bright Line Watch’s key findings:

- Partisanship outweighs all else for both Democrats and Republicans. Both groups are approximately 19 percentage points more likely to select a candidate from their own party than one from the other party—an effect that exceeds those observed for candidate policy positions and support or opposition to democratic principles.

- Democrats, Republicans, and independents all punish candidates who violate democratic principles related to political control over investigations, judicial independence, and cross-party compromise. These effects are consistently negative across all partisan groups and range from 4 to 13 percentage points.

- Americans diverge most dramatically along party lines on the democratic principle of equal voting rights and access. Democrats are less likely to back candidates who endorse legislation requiring voters to show ID at the polls, whereas support for these candidates increases by 8 percentage points among independents, and 17 percentage points among Republicans.

According to Bright Line Watch, the findings indicate a broad consensus in support of several key democratic principles. However, the political scientists warn that the high levels of partisanship “create a context in which such principles can be called into question and politicized.”

- Read more here about past Bright Line Watch findings.

- Listen here to an interview with Bright Line Watch’s Gretchen Helmke and Mitch Sanders about the resilience and state of U.S. democracy.