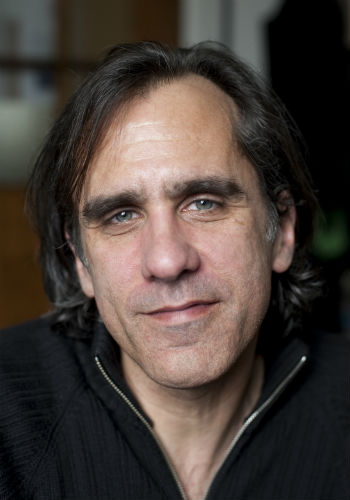

When John Ashbery died this September, at the age of 90, he was widely memorialized as one of the greatest American poets.

“I think he had probably the largest vocabulary of any poet after Shakespeare,” says James Longenbach, the Joseph Henry Gilmore Professor of English. “That was part of the thrill of his poems. And of his person.”

He knew Ashbery both professionally and personally. They first met when Ashbery received an honorary degree from the University in 1994. It was the beginning of a long friendship that also included novelist Joanna Scott, to whom Longenbach is married.

Ashbery—who maintained lifelong ties to his Rochester birthplace—published more than 20 volumes of poetry. Among them are The Tennis Court Oath (1962), The Double Dream of Spring (1970), Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975)—for which he won the Pulitzer Prize—Where Shall I Wander (2005), and Breezeway (2015).

In a Boston Review essay, reviewing Where Shall I Wander and a collection of Ashbery’s prose, Longenbach wrote in 2005: “No one else can write like this, and we are lucky to be alive at the same moment as the one person who can.”

What was John Ashbery like?

If anyone could be called the greatest living poet in the English language, it would be he. I’d read him, and written about him, for years before I got to know him. But really, Joanna and I got to know him less in the space of poetry than in the space of daily life—which, for him, was the space of poetry, because he was miraculously and unpretentiously devoted to the minutes of experience as they went by. He was interested in everything—he wanted to talk about anything, everything. And his poems are like that, too.

Some critics and readers have characterized his work as determinedly obscure. What do you think of that?

He has a reputation for being a very difficult poet, but I really don’t think that’s true. I think he only seems that way because people don’t generally spend a lot of time reading poetry. But if you do read a lot of poetry, his poems don’t seem of a different order of experience than those of Wallace Stevens, or Wordsworth, or John Donne.

People emphasize one side of his work all the time: that there’s a kind of disjunctiveness to it. Pronouns get messy, and things don’t match up, and you move from one level of diction to another with wild swiftness.

If it were just that, I think the poems would seem more available, because what that is combined with—and this is what people don’t talk about so much—is incredibly elegant syntax, usually long sentences with gorgeous subordinate clauses. It sounds like the syntax of logic, and of cause and effect.

But the material that’s in those sentences doesn’t match up with it, and that’s the distinctive thing about him as an artist of the English language. And it’s what can make his poems seem paradoxically more difficult. On the one hand, they sound very familiar and sense-making. And on the other hand, they don’t. Once you notice that, he doesn’t seem that different from Stevens or Wordsworth. He is different, but he’s also explicably a part of the tradition of English poetry.

Did knowing him change the way you read his poems?

What I discovered in getting to know him is that he was a very shy person. I could feel that in the poetry. I felt more strongly the undercurrent of sweetness and a kind of reticence, a boyishness that distinguished him in person and was there in the poetry.

He loved ordinary life, and he made his poems out of it.

What do you value most in his work?

One, a thing that you feel with any writer for whom you want to dare to use the word “great”: he’s distinctive and yet conversant with the entire tradition of poetry before him. He gathers everything up, and you can talk about his relationship to writers in the past who might seem antithetical to each other. There’s a great gathering force there.

And the other is the signature of his style that I mentioned earlier: it combines an elegant, extended, rational syntax with discombobulated, all-over-the-map, vocabulary-driven disparities of diction. And there’s really nothing quite like that. He has a lot of imitators, but they usually just imitate the crazy, mixed-up diction. They don’t have the power to make those sentences that he did.

Is there a poem you’d recommend for people who’d like to start reading Ashbery?

The first poem in his collection Your Name Here is called “This Room.” It’s a short poem that is very indicative of how his poems work, but also of the pleasure of his poetry.