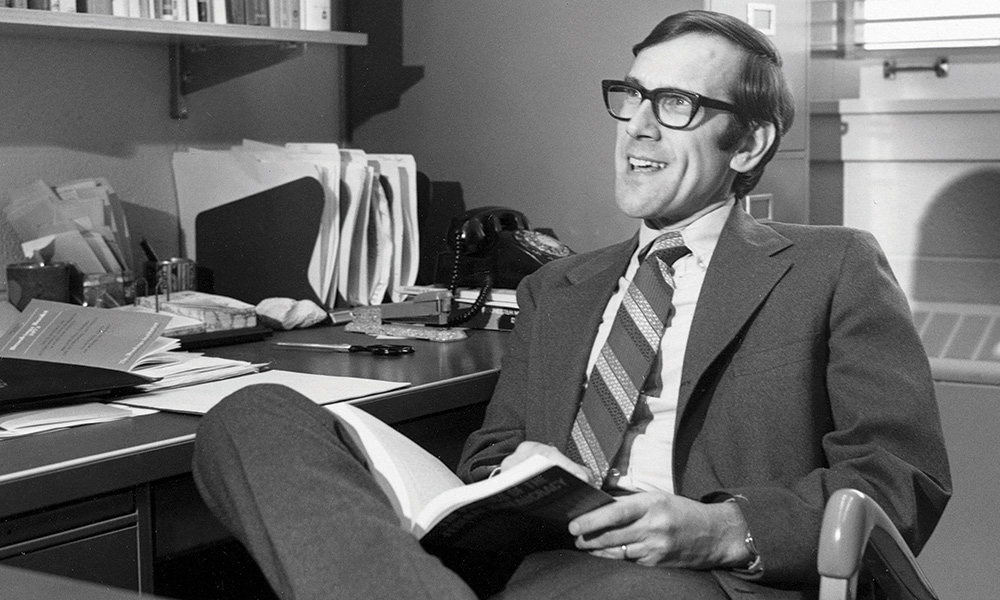

Richard (Dick) Fenno Jr., considered a giant among 20th-century scholars of American politics, is being remembered by colleagues, former students, and friends as a trailblazing political scientist whose 19 books on Congress and its members set a standard for the field.

Fenno, who last held the title of Distinguished University Professor Emeritus at the University of Rochester, died on April 21 at the age of 93 from complications associated with presumed COVID-19.

Tribute to a pioneering colleague

Rochester’s Department of Political Science remembers Richard Fenno.

Share your tributes, condolences, or memories of Fenno via email. Tell us your name, your affiliation with the University, and your public message, which will appear on the messages and condolences page.

In Memory of Richard Fenno

Contributions in Fenno’s memory can be made to the Department of Political Science’s

Richard and Nancy Fenno Summer Fellowships in American Politics and Policy.

For more about Fenno

Visit the official Richard Fenno website, assembled by his former students.

“Dick and Woodrow Wilson were probably the two greatest scholars of Congress in the 20th century,” says former colleague Lawrence Rothenberg, the Corrigan-Minehan Professor of Political Science at the University of Rochester, who saw Fenno and his wife, Nancy, in many ways as surrogate parents.

The Fennos were a team—childhood sweethearts married for 71 years—who grew up together and “fit like a glove,” says Rothenberg, who used to spend countless hours at the couple’s former home in Penfield, a Rochester suburb.

What set Fenno apart early on in his career was his headlong approach to research—preferring to dive right in alongside his study subjects, such as senators (and later vice president) Dan Quayle, Ohio’s John Glenn, New Mexico’s Pete Domenici, Pennsylvania’s Arlen Specter, and North Dakota’s Mark Andrews —looking right over their shoulders to observe their often messy political deal-making in real time, rather than taking a broad, institutional view.

“Fenno created the modern study of Congress with his pathbreaking scholarship on House and Senate members, legislating in the halls of Congress and campaigning on the streets of their districts,” says Wendy Schiller ’94 (PhD), a professor and the chair of political science at Brown University, herself a Fenno student. “He thought like a political scientist and wrote like a novelist.”

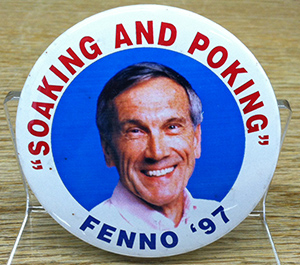

The invention of ‘soaking and poking’

“I began with a study of the power of the purse, how politics plays out as Congress goes about appropriating funds,” Fenno told Thomas Fitzpatrick for a 1991 Rochester Review story. “That led me to realize that the real work and real life of these politicians goes on not on the floor but in committees and subcommittees.” A book followed. “It gradually came to me that what they do in these committees is vitally connected to how they perceive their home districts and states,” Fenno said. “That’s when I started hanging around with politicians in earnest.”

Mind you, not just hanging out. “Soaking and poking” is how Fenno described his method, which has since become accepted political science terminology. For decades he had been both soaking up the details of governing and poking into the minutiae of campaigning.

He applied that same principle to his students. In 1968, when Rochester undergraduate Robert Sachs ’70 approached the political science department with the idea of becoming an intern for New York Senator Charles Goodell for course credit, an idea was born. Fenno, along with student charter member Sachs, started the University’s Washington Semester Program, which endures today. The program annually selects several political science students to work as full-time interns in Congress, the executive branch, and party campaign committees, as well as with lobbying, advocacy, and policy groups.

“The theory is that the way to learn about the congressional system is to go down there and work for a semester,” Fenno told Rochester Review in 1999. The students may start out opening mail and doing other clerical chores, but over time, he said, “they become an integral member of the staff—and that’s the way they learn.”

And learn they did. Heather Higginbottom ’94 says the opportunity to work on Capitol Hill “day in and day out and to have a front-row seat for how legislation was made”—cemented her commitment to pursue a career in government and politics. She made good on that promise and went on to become the first woman to serve as Deputy Secretary of State in the administration of President Barack Obama. She remembers Fenno most for his kindness.

“He was iconic in his field and at the University, yet he was completely approachable and accessible to us. He was committed to our success during the program and afterwards.”

Decades after her Washington internship, Higginbottom continued to receive handwritten letters from him, supporting her roles in government. “They moved me, and I continue to cherish them.”

What is the ‘Fenno paradox’?

As a scholar, Fenno focused on Congress. He was the first to point out the apparent disconnect between low congressional approval and high incumbency in his 1978 book Home Style: House Members in Their Districts.

It was this observation—that people generally disapprove of the US Congress as a whole, but support the representatives from their own congressional districts—which became known as Fenno’s paradox.

Home Style, meanwhile, would go on to win the Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award for best book in political science. Setting the gold standard for congressional scholarship, the American Political Science Association eventually named an award after him—the Richard F. Fenno, Jr. Prize for the best book in legislative studies.

Fellow political scientists and peers—the late Nelson Polsby and Eric Schickler at the University of California, Berkeley—wrote about Fenno that “in the nearly 200 years since the founding of the American nation, no scholar has contributed more to the understanding of its legislative branch, the US Congress.”

Born on December 12, 1926, in Winchester, Massachusetts, Fenno served in the Navy during World War II. In 1948 he received his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and then married Nancy. After earning a PhD in political science from Harvard University in 1956, Fenno joined the University of Rochester’s Department of Political Science barely a year later.

By all accounts, Fenno was a curious mind, genuinely interested in others, with strong people skills to boot. Throughout his long life, he kept in touch with scores of former students, politicians, journalists, collaborators, and colleagues. Those character traits helped him gain access and build the kind of relationships he enjoyed with legislators and their staffs. As Fenno’s reputation grew in tandem with his impressive body of work, prestigious job offers from elite schools came his way—including from his alma mater Harvard.

Yet, he seemed little interested in status and turned them down.

Instead, during his nearly 50 years at the University, he, together with William Riker, put the Rochester political science department on the academic map, building its lasting national reputation and educating generations of scholars who continue to shape the discipline of political science today. The two men, it seemed, proved a natural yin and yang.

Putting the ‘Rochester school’ on the map

Riker relished being chair, colleagues attest. For his part, Fenno made it clear that the only way to persuade him to leave was to force him to helm his own department. “Bill Riker happily lived his life mainly in Harkness Hall, while Dick was well connected to the outside world academically and in terms of politics and just needed to be out there,” Rothenberg recalls.

Their mutual respect and friendship went so far, according to several colleagues who tell the same story, that Fenno refused to be considered for the presidency of the American Political Science Association (APSA) until Riker had been elected to the post first. In the end, Riker served as president for the 1982–83 term, and Fenno followed for 1984–85.

James Johnson, a professor of political science, arrived at Rochester about three decades after Fenno. Johnson’s initial job interview proved somewhat unusual.

“We went into his office, Dick leaned back in his chair, as he often did, and we talked about the Boston Celtics. He had a large Celtics poster in the corner of the office,” Johnson says. “We might’ve talked about my work a bit, too. But we bonded as Celtics fans.”

According to Johnson, Fenno was an equal partner with Riker when it came to the intellectual success of the department. “Bill pushed the discipline in methodological terms to integrate statistical methods and formal models. Dick provided considerable substantive ballast—his early work on congressional committees laid the groundwork on which the techniques could be used.” Fenno would prove a consistent advocate for qualitative methodological approaches.

As Fenno’s star rose, he was eager to ensure others got a fair chance, too. During his tenure as APSA president, his main goal was to increase the participation of minorities and underrepresented groups in the field. The result was the Association’s Jewel L. Prestage and Richard F. Fenno, Jr. Endowment for Minority Opportunities, which promotes and supports opportunities for minority students contemplating advanced training in political science.

Diversifying political science

Back home in Rochester he pushed the department to diversify its faculty. Fredrick Harris started in 1994 as an assistant professor of political science, the department’s first African American tenure-track hire.

“Dick was a giant in the field of American politics, the most important political scientist studying the US Congress in the latter half of the twentieth century,” says Harris who left Rochester as a full professor at the end of 2006 to become a professor of political science at Columbia University, where he also serves as dean of faculty in the social sciences.

“He is the reason I decided to take the job at Rochester even though I had verbally agreed to take another job in my hometown,” Harris remembers. He changed his mind because “Dick saw the value of my scholarship more than other mainstream political scientists and what I had dedicated my life to studying—black politics.” Ultimately, Harris says, it came down to three words Fenno wrote in a note to him in 1993: “We need you.”

Fenno had persistently pushed the department to look for minority faculty members “in part because he rightly believed that American politics is thoroughly inflected by race,” his former colleague Johnson says. “He understood that the underrepresentation of African Americans in the profession required institutional remedy”—be it at the departmental or national level.

Despite his many accolades and accomplishments, it never seemed to be about him. Unpretentious and modest, he was immensely proud of his graduate students and their work, recalls former colleague Gerald Gamm, a Rochester professor of political science who served as chair of the department for a total of 13 years.

But Fenno’s modesty knew one exception.

According to Kenneth Shepsle ’70 (PhD), the George D. Markham Professor of Government at Harvard, Fenno loved his wife and sons, Mark and Craig, most. After his family, in no particular order, he loved the University and the department. He loved being able to pursue his scholarly curiosity without constraint, and he loved keeping in close touch with his students.

“But somewhere pretty high up on the list,” says Shepsle, who earned his PhD under Fenno and Riker, “was the pride he took in the colorful annuals he planted each summer along the walkway of his Cape Cod home in Truro. Dick was never a man to brag, never someone to swell with pride, except on the subject of his flower garden.”

What struck students and colleagues alike was his approachability and genuine warmth. Fenno’s office door in the department usually stood wide open. He would call out to passing colleagues and invite them in to talk about their research, ask about them. He usually whistled.

“I think that was just the musical manifestation of Dick’s inner joy,” muses Gamm.

In 1997 at the annual APSA conference, a panel of political scientists were eulogizing a fellow congressional scholar, Harvard’s late Douglas Price.

As is frequently the case, the speakers’ memories were as much about themselves as they were about the dead man. Then it was Fenno’s turn. His remarks were carefully written out. “He told stories about Doug, he told stories about Doug’s work, and he told stories about Doug’s influence on people,” says Gamm, deeply moved. “Dick made it through all his remarks without mentioning himself once.”

John Duggan, a professor of political science and economics and the current chair of the Rochester political science department, was a junior faculty member when Fenno was still active in the department.

“He would often drop by my office or stop me in the parking lot to offer encouragement. He sincerely wanted to know how I was doing, and he never seemed too short on time to have a meaningful conversation. As a young scholar, I was struck that a giant of the political science discipline had the generosity to spend his time and attention on me, but that was very much typical of Dick.”

Nor did that empathy stop at the hallways of power. Riding the elevator with Fenno one day in the Capitol building in Washington, DC, a congressman joined them, Gamm remembers. Although Fenno had already abandoned research on him, the congressman greeted the Rochesterian like an old friend: “Where have you been, Dick? Why don’t you come and visit me more often?” he implored.

Not many researchers get that kind of enthusiastic response in Washington, notes Gamm dryly, whose work shares a focus on Congress.

Giving back to Rochester’s students

In 2011, the Fennos talked to the department about their desire to give back in a meaningful way, pledging the initial seed money for an undergraduate fellowship program. Other donors quickly followed suit and the Richard and Nancy Fenno Summer Fellowships in American Politics and Policy was born.

When Fenno officially retired in 2003, he had bequeathed to the University his trove of papers, interviews with congressional leaders, manuscripts, and talks. All of these materials were made accessible online by his former students—Sachs being one of them—together with the help of staff at Rush Rhees Library.

Sachs, who went on to become a successful attorney and business executive in the cable TV and telecommunications industries, first got to know Fenno in 1968. He calls Fenno a “teacher, mentor, and friend—all in one. His infectious curiosity, positive attitude about life, and genuine good nature made him a joy to know.”

Fenno remained enthusiastic about his research, students, and colleagues right up to his last academic days. While he had officially retired a decade earlier, he published his last book, The Challenges of Congressional Representation in 2013. Until a few years ago, Fenno—already in his late 80s—could still be seen most days on campus.

“He never stopped going until he couldn’t any longer,” says Shepsle.

Serious about his work, which he insisted on doing in silence, he kept returning to one of the small library carrels on campus, the last space Fenno gave up at the University.

“I think that there were many students and academics who felt that Dick had a special interest in them,” Rothenberg says. “The truth was that he had a special interest in everyone.”

Fenno is survived by his wife, Nancy, of Rye, New York; his son, Craig Fenno, of Armonk, New York; daughter-in-law, Sharon Fenno, of Albany; sister, Elizabeth Blucke, of Hingham, Massachusetts; and grandchildren Zachary Fenno, of New York City, and Sarah Fenno, of Armonk. Mark Fenno, the couple’s oldest child, and Amy Fenno, their daughter-in-law and Craig’s wife, predeceased him.