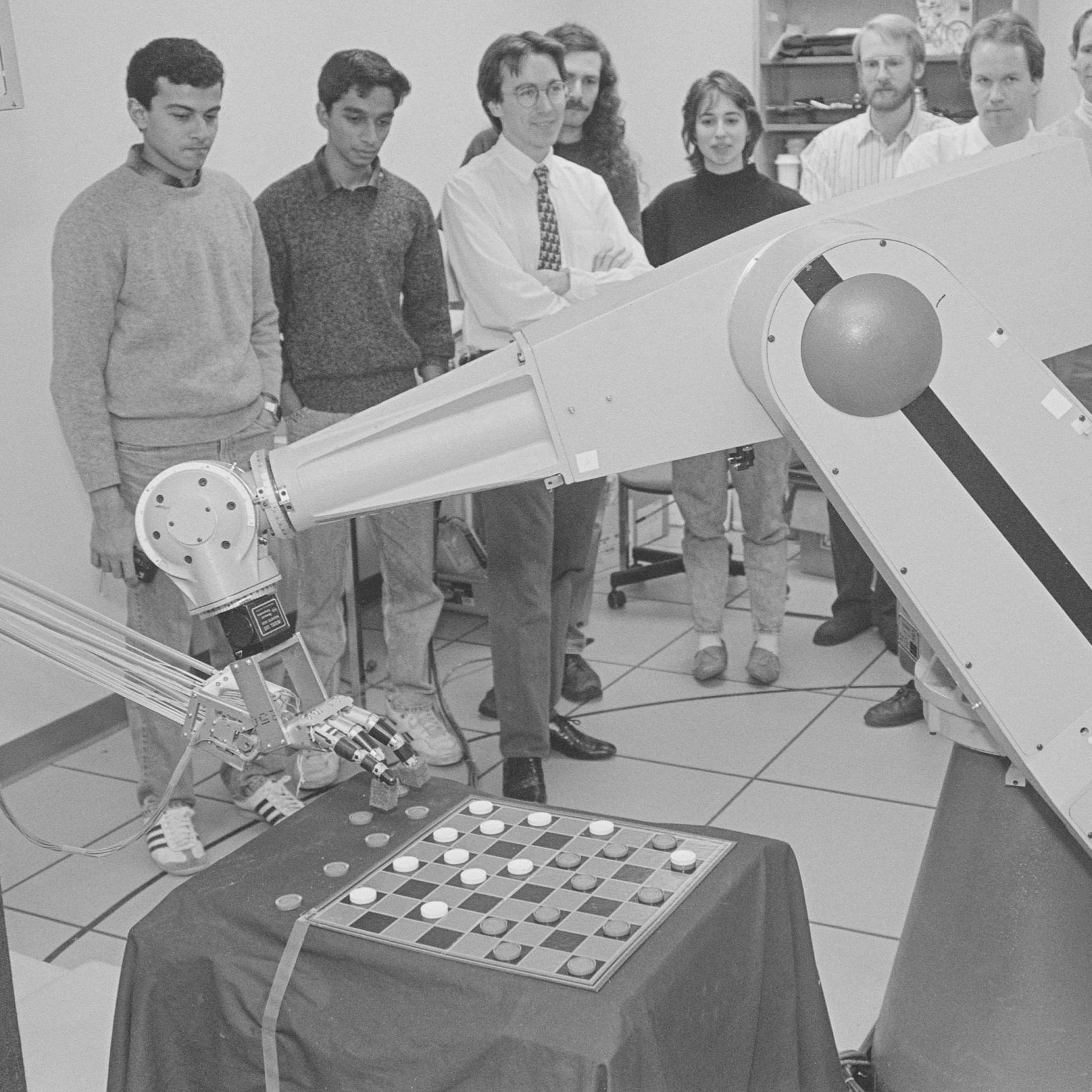

The focus on AI created opportunities for collaborations with faculty in cognitive science (later the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences), the Center for Visual Science, the Design Automation Project, and the Laboratory for Laser Energetics.

Says Michael Scott, a professor of computer science and the Arthur Gould Yates Professor of Engineering, who came to Rochester in 1984, “Computer science is an interdisciplinary field, but I think it’s more the case here than almost anywhere.”

A new major

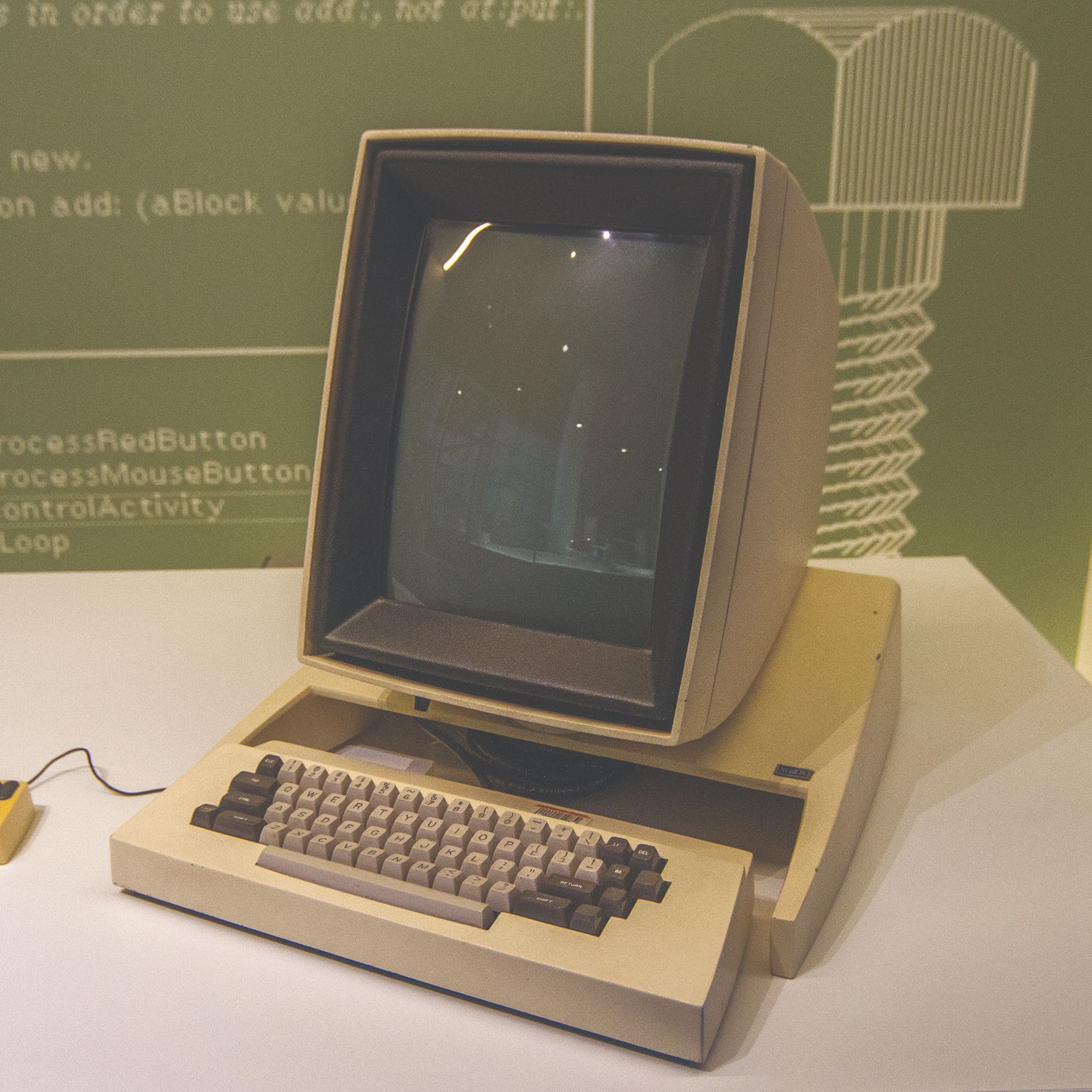

By the 1990s, the promises of ARPANET had borne fruit, and the technology evolved into the internet, connecting millions of computers around the world. Meanwhile, British scientist Tim Berners-Lee had proposed an application for the internet: a method to create pages, with unique addresses, giving networks a new and compelling purpose. The World Wide Web, as it was soon known, spread information with ease and at a speed (even in its first days) previously unknown. The dot-com era had arrived, and with it, exploding interest in the study of computer science.

The department had solely been offering graduate degrees, but nationwide, the demand for computer science was high enough that the department introduced undergraduate degrees and a minor in 1995.

The undergraduate program was a significant development for the department, and leadership had to be careful to integrate undergraduate education while preserving the culture that had allowed the department to thrive.

“When I arrived in 1989, the culture was 100 percent focused on research and doing something amazing,” says George Ferguson ’95 (PhD), director of the department’s undergraduate program and a professor of instruction.

That same spirit infuses the undergraduate program, which has a heavy research focus and emphasis on “breadth and the foundation of the discipline as a whole,” he adds. That approach fosters “graduates who understand enough to learn new things, which is essential in a field that has been evolving constantly since its inception.”

At the same time, the department has been deft in attracting students with wide interests. “The program was smartly designed from the beginning so that you could either pursue a bachelor of arts or a bachelor of science,” Ferguson adds. The modified requirements of the bachelor of arts made a computer science degree more accessible to students also pursuing degrees in fields from physics to art history.

The program’s first graduating class in 1996 included 10 students, and by 2003, that number had increased fivefold.

Post-Y2K challenges

The dot-com bubble burst of 2000 put a pause on the undergraduate program’s growth. As tech companies folded, some prospective students became wary of pursuing careers in computer science.

Christopher Stewart ’09 (PhD), now a professor of computer science at Ohio State University, says that when he arrived as a PhD student in 2003, the discipline was facing intense challenges beyond the financial sector as well.

For the past few decades, the computer industry had relied on the expectation, largely borne out by experience, that the number of transistors on a microchip would double about every two years, at nominal cost. Accordingly, computers would continue to get smaller, faster, and cheaper. The trend became known as Moore’s Law and, not really a law at all, scientists began predicting its end. Similarly, Dennard scaling—the physical principle that enabled transistors growing in potency to consume less power—was running out as well.

Moore’s law and Dennard scaling, says Stewart, “were these things that allowed us to keep building sequential programs for so long. It was an exciting time, and it was fun to be a part of that phase of computing.”

Stewart, who focused on computing systems, says much of the research at the time focused on parallel computing—that is, how to break down large, complex problems into smaller, independent groups of calculations, all of which could be carried out simultaneously across multiple processors relying on shared memory. Although at first Stewart did not understand what parallelism would lead to, he received an answer that proved to be decades ahead of its time.

As a beginning graduate student, “I was really trying to understand the field and where things were headed,” he recalls. He asked Michael Scott, the leader of the computer systems research group, what was likely to happen to the field of parallel computing.

“I asked [him], ‘What are we going to do? Even if we do get all of this parallel programming done, we already know how to write’ whatever single-coded thread was dominant that day. He told me, ‘Chris, if we can do parallelism right, we can reach new heights with AI.’ That was at least two generations of insight ahead of where computing would go.”

BRAIDing a future

By the mid 2010s, computer science had rebounded from the dot-com bust and experienced a second surge in enrollment. With that growth also came efforts to diversify the student body, particularly to get more women to pursue computer science degrees at Rochester.

Sandhya Dwarkadas joined the department as an assistant professor in 1996 and later became the Albert Arendt Hopeman Professor of Engineering and from 2014 to 2020, chair of computer science. Dwarkadas, now a professor and chair of computer science at the University of Virginia, recalls in those early years a tight-knit and collegial department but one that had few women.