The 700-year-old manuscript is the first in a new University of Rochester library collection that honors historian Richard Kaeuper.

Last June, two University of Rochester colleagues—a historian and a librarian—were thinking out loud: how best to commemorate a preeminent medievalist and immensely popular history professor who was about to retire after more than half a century of service to the University?

Richard Kaeuper, now the Franklin W. and Gladys I. Clark Professor Emeritus of History, taught and researched at Rochester for 52 years.

Laura Smoller, a professor of history and then chair of the Department of History, and Anna Siebach-Larsen, the director of the Rossell Hope Robbins Library and Koller-Collins Center for English Studies, were hunting for something special. Something that would at once be a lasting extension of Kaeuper’s work; enhance the University River Campus libraries’ existing collections across medieval history, literature, art, and culture; and serve as a valuable research and teaching object for scholars and students alike.

The two were thinking modestly—maybe a small medieval charter. They enlisted Miranda Mims, the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), who immediately offered her enthusiastic support. Mims agreed that any Kaeuper manuscripts would be housed in safe, climate-controlled conditions at RBSCP.

Meanwhile, staff at the University’s advancement office and the library started reaching out to Kaeuper’s former students. “Honestly, I thought we might raise about $1,500 or so,” says Smoller. “But then these really huge gifts started coming in.”

Thanks to the generosity of lead donor Paul Kreuzer ’72—and bolstered by David Burkhardt ’88, whose gift kept the momentum going—the fund grew rapidly.

Bowled over, the duo began to dream big.

Suddenly an entire medieval book, known as a codex, was a real possibility. More specifically, a medieval legal treatise—because Kaeuper is a preeminent expert not just on chivalry, but also on medieval European law, public order, administration, and finance.

Siebach-Larsen began to scour auction catalogues and talked to dealers to find a suitable candidate. She zeroed in on a particular manuscript, a guide for lawyers on how to argue cases and respond to various legal situations.

Eureka!

“Essentially, it’s a lawyer’s handbook,” says Siebach-Larsen. “We purchased it in honor of Dick because he’s a monumental historian of legal history, particularly for France and for England in the high and late Middle Ages. It really speaks perfectly to both his teaching and to his own research.”

Smoller adds, “It just seemed such a perfect fit for Dick’s expertise.”

‘Kaeuperites’ unite

Many of the donations were accompanied by kind notes from alumni to their former professor, recalling fondly Kaeuper’s teaching and how it affected their personal and professional lives long after their time on campus.

One of them, Jeffrey Lehn ’05, has been a NYPD officer for the last 17 years. He writes that Kaeuper’s seminar course on chivalry, “where I had to read and process an incredible amount of source material as well as contemporary analysis,” and Kaeuper’s course on research, which for him meant combing through the written English record for Stephan Fulborne, set him on track to become a detective.

“Luck and hard work aside, I feel that I was better prepared for casework than many of my peers,” writes Lehn. “A history paper is remarkably similar to a detective’s case. Both utilize times, places, quotations, and outcomes in order to prove a thesis.”

Kaeuper’s very last doctoral student says he was fortunate to snag the popular scholar as his Doktorvater before his retirement.

“Anyone who has worked with Dick knows him to be a patient and caring mentor as well as a rigorous and passionate scholar,” says Tucker Million ’21 (PhD). “Above all, Dick knew that the proper study of history takes time. He gave a lot of his own time to helping his students.”

Million is pleased that a collection of medieval manuscripts bearing Kaeuper’s name will “continue to challenge, enlighten, and inspire the Rochester community for many years to come. I can think of no one more deserving of such a legacy than Dick.”

To this day, Kaeuper’s graduate students unabashedly identify themselves as “Kaeuperites,” adds Smoller. Like any good graduate mentor, she says, Kaeuper succeeds because he is “a superlative scholar.”

Indeed, his work has earned him numerous honors, including being inducted as a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and of the Medieval Academy of America. He is a winner of the Verbruggen Prize awarded by the De Re Militari Society and has landed research grants from the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Woodrow Wilson Foundation.

Kaeuper’s instruction at the University has left an indelible mark both at the undergraduate and graduate levels and has been recognized with the Goergen Award (2013), the Student Association Award for Teaching Excellence in the Social Sciences (1999), the Edward Peck Curtis Teaching Award (1990), and the Student Association Teacher of the Year Award (1986).

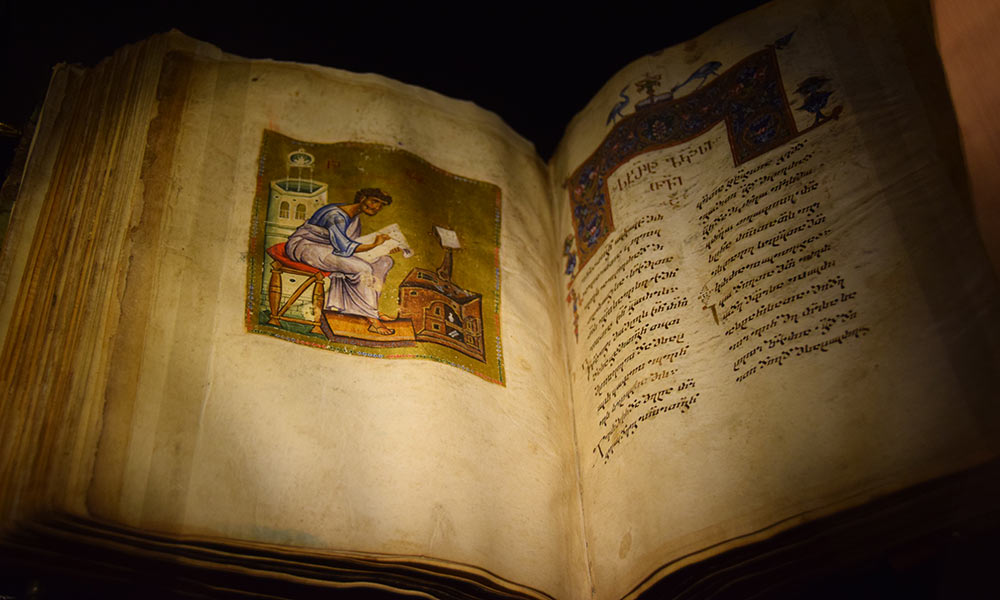

The gifts will be used for acquiring more items and maintaining the collection of medieval manuscripts that will ultimately support medieval studies research and teaching at the University. The newly minted Richard W. Kaeuper Collection of Medieval Manuscripts also includes a medieval manuscript donated by Kaeuper himself: a 1297 Parisian letter from the important Augustinian theologian and ecclesiastic Giles of Rome regarding a property matter.

Bonjour, j’arrive: the manuscript makes it to Rochester

Delayed by pandemic restrictions, the manuscript finally made its way from France to Rochester this summer. It’s the first item in the new Kaeuper Collection that will be housed in RBSCP, where many of the University of Rochester’s rare and unique historical materials are held.

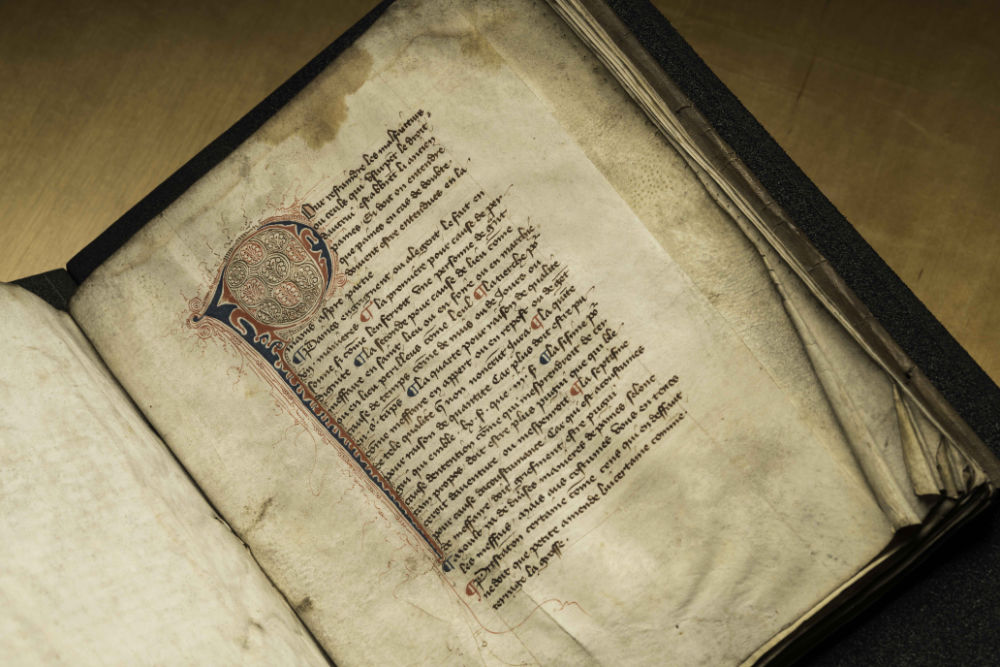

Authored in Paris by Pierre and Guillaume de Maucreux around 1330 to 1340 CE, the manuscript—Ordonnances de plaidoyer de bouche et par escript (Ordonnances governing legal pleas made orally and in writing)—consists of 36 parchment folios, written in chancery hand. Pierre de Maucreux was a famous French lawyer whom the French king Charles IV ennobled in 1326, and Guillaume was his brother.

“The extravagant penwork decoration is unusual for this type of manuscript,” says Siebach-Larsen of the nearly 700-year-old manuscript that comes in its original binding of limp parchment folios, replete with stains from centuries of hands touching the pages. And there are the occasional wormholes, all par for the course. While other pages have some decorated letters, none rise to the intricacy and elegance of the highly stylized P, the first letter on the first folio, which marks the start to the very first word—“pour” (for).

Studying an old manuscript—its materials, ink, handwriting, stitching, and text marks, as well as tracing its physical whereabouts throughout history—is often true detective work.

In this case, the inscription on the back is in Dutch (“Exstrait van eene Deels vanden Rechten ghetrocken vute loix ende ghetranslateirt vanden latine In fracoit”) and informs the reader that the manuscript is a translation from Latin to French. It also reveals that at some point in the 15th century the manuscript had been in the Low Countries (now the regions of the Netherlands, Flanders, and Belgium) or had been owned by a Dutch speaker.

What makes this manuscript special?

It’s one of only two existing copies of an influential legal treatise for the Parlement de Paris. In fact, until this manuscript recently surfaced, scholars believed that there was only one copy.

While the Rochester manuscript was copied soon after the composition of the treatise, the other manuscript, held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, was copied more than 100 years later in about 1473. The later manuscript at the Bibliothèque nationale has several mistakes indicating that the scribe was not familiar with French legal language, says Siebach-Larsen. The Rochester copy, which may have been copied from the original manuscript, differs from the later manuscript in its writing conventions and content and is much closer to the original.

A medieval handbook for French lawyers, the manuscript is basically a proto how-to guide. To historians, it represents a vital early source for the history of the Parlement de Paris, which functioned as France’s supreme court from the 13th century until 1789. The manuscript contains definitions of juridical terms and concepts, various types of legal pleas, explanations of legal defenses, and how to respond to them—a kind of early textbook that would have been used by young lawyers and legal practitioners across French provinces and various types of French courts.

Yet, as is often the case with old manuscripts, a few parts are missing in action. According to the table of contents, the text should have ended with a discussion of legal procedures, but the Rochester manuscript is missing that section.

‘The skin I love to touch’

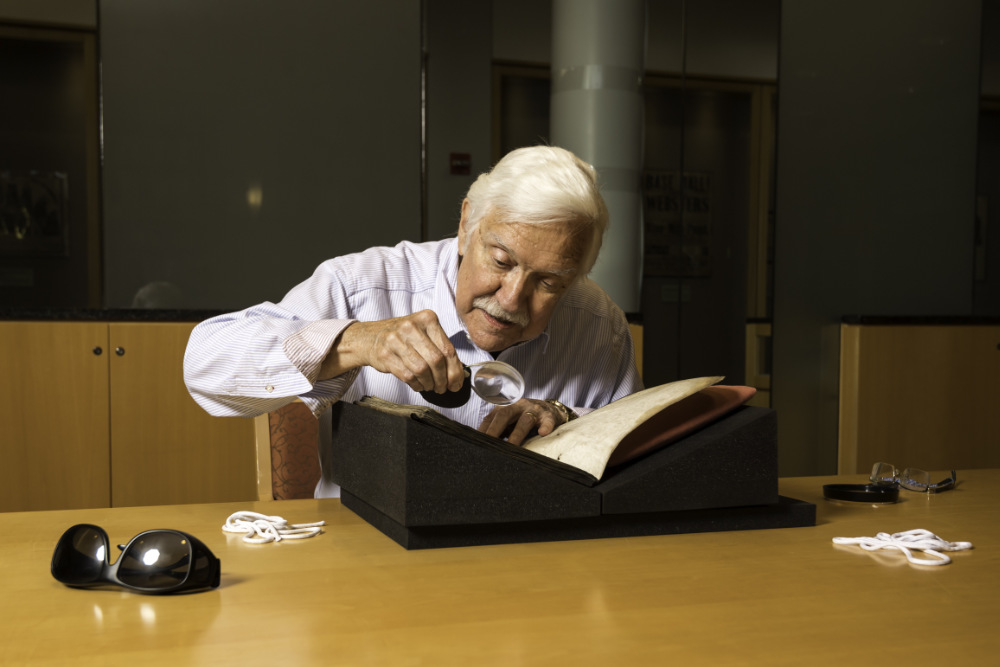

The manuscript’s quirks didn’t dampen Kaeuper’s enthusiasm one bit at the official unveiling this summer when he finally got to meet the manuscript in the flesh.

“It’s a wonderful and imaginative idea,” says Kaeuper who was floored by the long list of donors, some of them students he taught nearly half a century ago. “I was utterly taken by surprise, really gob smacked.” Touched by his colleagues’ thoughtfulness, and his former students’ “generous contributions and lovely notes,” Kaeuper says he feels the manuscript really represents a “continuation of something we did together.”

“I’m reminded of the old ad for some kind of soap, with the tag line, ‘This is the skin I love to touch,’ says a beaming Kaeuper while stroking a leaf of the manuscript. “This is the skin I love to touch.”

Siebach-Larsen meanwhile loves that the manuscript is in French instead of Latin, because French represents a lower language barrier to most students, she says.

“It’s a great opportunity for both graduate and undergraduate students to grapple with a valuable manuscript, to hopefully do projects on it,” says Siebach-Larsen, emphasizing that the library is dedicated to making its manuscripts available as hands-on experiences to anyone who wants to use them.

Touching a centuries-old piece of parchment or vellum prompts in her a “true visceral reaction,” says Smoller. “That’s when I feel the people I write about are real, something that you wouldn’t get by just reading their writing. It’s a genuine connection.”

And that’s something the historian hopes students will be able to experience, too.

Special thanks to the many people—including Pamela Jackson, Jenna Hiller and Thomas Cassada from the Office of Advancement, Lydia Auteritano and Sharon Briggs from the University’s River Campus Libraries, as well as nearly one hundred alumni—who helped make the Richard W. Kaeuper Collection of Medieval Manuscripts at the University of Rochester a reality.

Alumni, colleagues, friends, and medievalists who’d like to support the Kaeuper Collection can contribute using this secure online form.

Read more

Turning the gears of an early modern search engine

Turning the gears of an early modern search engine

A collaboration between librarians and engineering students, the book wheel in Rossell Hope Robbins Library is a recreation of a 16th century design, solving the problem of needing access to multiple books at the same time.

Trained as a scholar of medieval literature, Gregory Heyworth has become a “textual scientist.” Using a transportable multispectral imaging lab—the only one in the world—he recovers the words and images of cultural heritage objects that have been lost, through damage and erasure, to time.

Every discipline in the University has its own way of constructing and thinking about time. Historian Richard Kaeuper offers his perspective on medieval studies and the technological measurement of time.

The future of the past

The future of the past Thinking about time

Thinking about time