The acquisition of Alaska by the United States on March 30, 1867, was dubbed “Seward’s Folly” or ridiculed as “Seward’s Icebox” by critics at the time. The eponyms refer to William Henry Seward (1801–1872), secretary of state under President Abraham Lincoln and President Andrew Johnson, and his role in brokering the Alaska Purchase from the Russian Empire. The price tag at the time for “Russian America”? $7.2 million, or 2 cents an acre.

Seward’s supposed folly would ultimately prove to be a shrewd bargain on the statesman’s part. In addition to the abundant natural resources available, Alaska became fertile territory for gold mining in the late 19th century (i.e., the Klondike gold rush) and then oil in the 20th century.

Seward’s son recounted his father’s response late in life when asked, “Which of your public acts do you think will live longest in the memory of the American People?” Seward replied, “The purchase of Alaska. But it will take another generation to find out.”

Several generations later, we can better understand Seward’s expansionist inclinations as we look through his papers and other memorabilia related to the Alaska Purchase. In addition to handwritten letters and official documents, there are newspaper accounts, a map of the Arctic shores, even a 14-karat gold cigar case decorated with iconic Alaskan scenes.

Today, the signing of the Alaska treaty is one of Seward’s most well-known and celebrated acts as Secretary of State. Meanwhile, the William Henry Seward Papers—which comprises family papers, political papers, financial records, photographs, diaries, newspapers, and artifacts spanning 150 years—is one of the largest and most frequently accessed collections in Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation at the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries.

(University of Rochester photos / J. Adam Fenster)

Authorization to negotiate

Signed by then-President Andrew Johnson, this document grants Seward the authority to meet with Eduard de Stoeckl, the Russian minister to the United States, to negotiate a treaty allowing the United States to purchase the Alaskan territory. This territory included Alaska, parts of northern California, and two ports in Hawaii.

After a long night of negotiations, Seward and de Stoeckl signed a treaty stating that the U.S. would purchase the land for $7.2 million (approximately $123.4 million today).

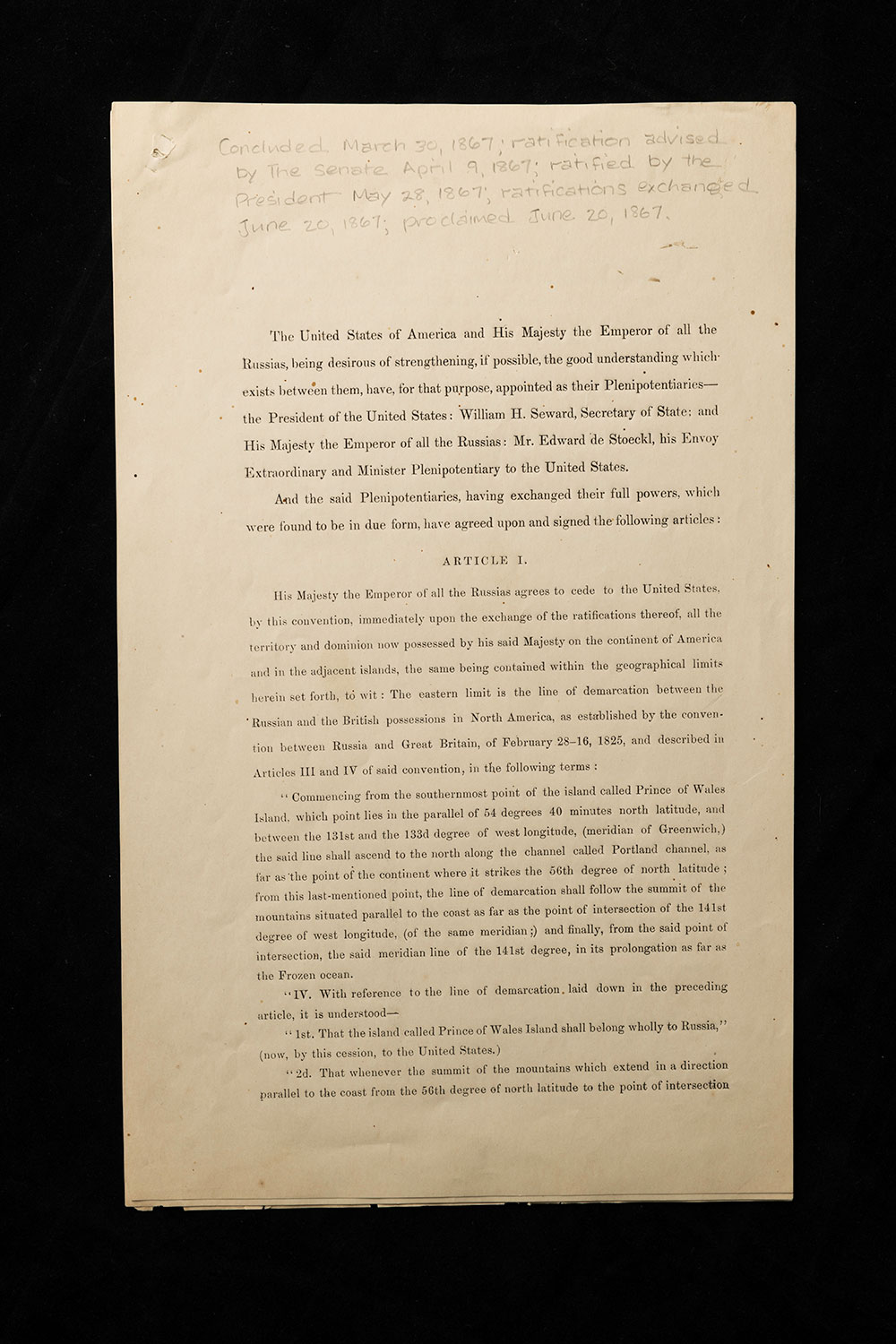

Trick or treaty?

The treaty outlines the geographical boundaries of the territory and establishes ownership of existing property. Russian citizens could choose to return to their home country within three years or remain in the territory to become U.S. citizens. Meanwhile, members of native tribes were not eligible for citizenship, but were still subject to the laws and regulations set forth by the U.S. government.

This is a copy of that treaty, which was approved by the senate on April 9, 1867, and ratified by the president on May 28, 1867.

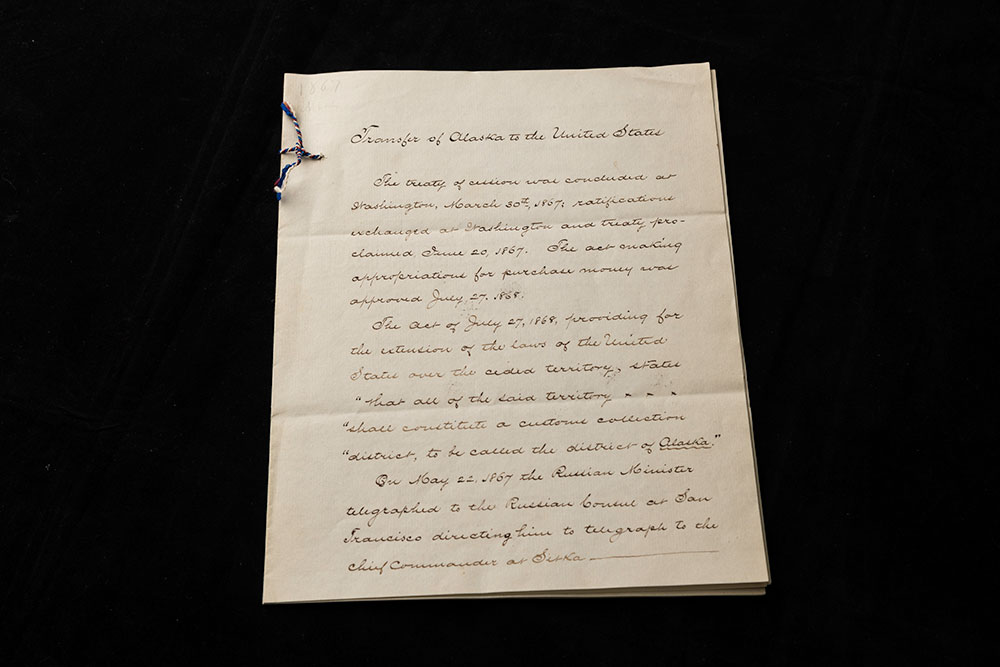

Firsthand account of the official handoff

The ceremony formally transferring the Alaskan territory to the United States took place on October 18, 1867. This document written in 1869 by John H. Haswell provides a firsthand account of the events of that day. Companies of American and Russian soldiers gathered at the governor’s house in Alaska. A ceremonial firing of guns followed, and as the Russian flag was lowered, the U.S. flag was attached and raised in its place to signal the transfer of land.

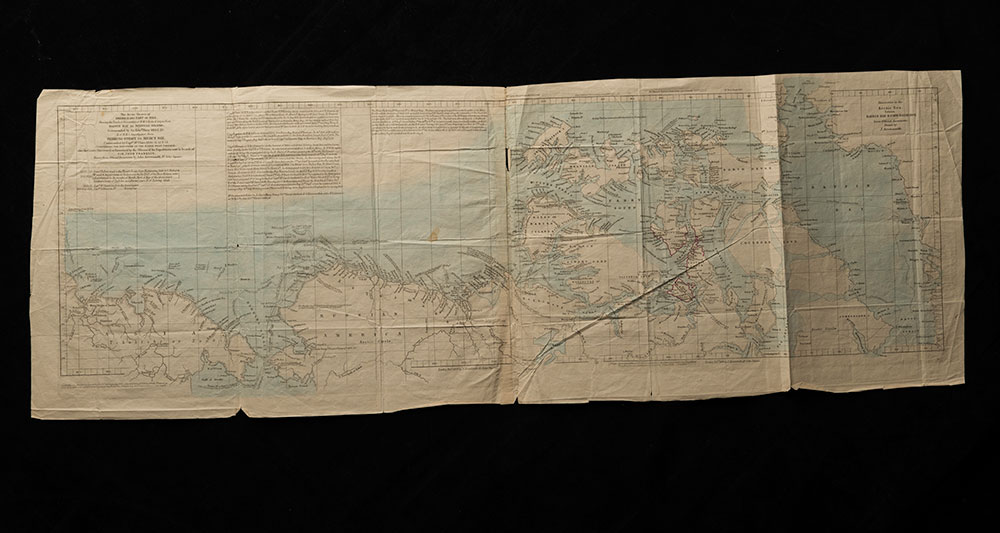

Make me a map

Arctic exploration increased rapidly throughout the 19th century as explorers from around the world sought to discover new passages. This 1859 map illustrates parts of Russia, Alaska, and Canada north of the Arctic Circle and features information about explorers who traveled different routes across the region. Names of explorers, dates when expeditions occurred, and landmarks discovered are all documented.

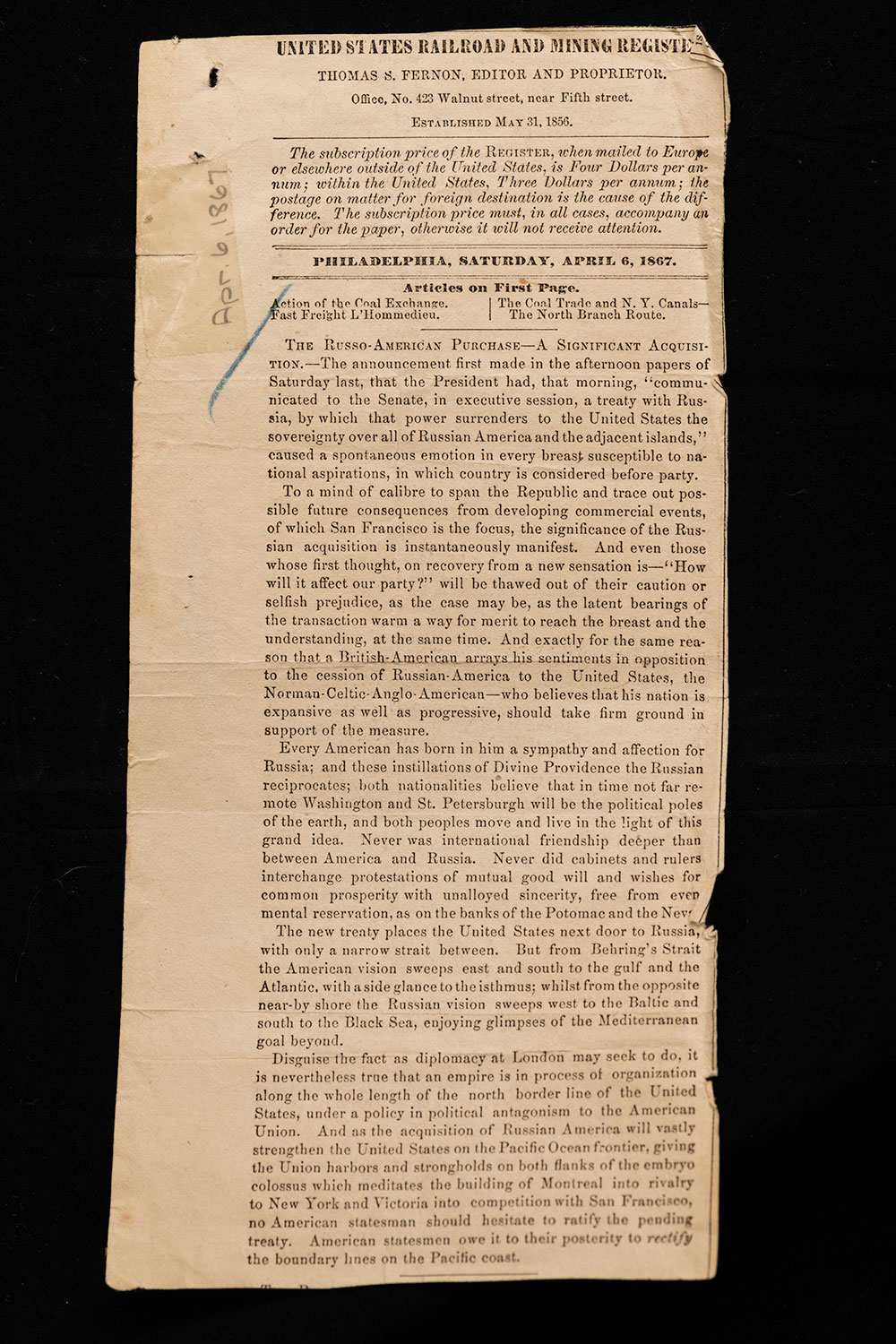

Extra! Extra! ‘The Russo-American Purchase: A Significant Acquisition’

This newspaper article was published on April 6, 1867, in the United States Railroad and Mining Register in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The article highlights the strength of the relationship between the United States and Russia following the creation of the Alaska treaty. The newspaper—along with many politicians of the day—viewed the acquisition as a significant asset, strengthening the country’s borders along the Pacific Ocean and supporting American expansionism.

Despite the ever-present idea of the Alaska Purchase as “Seward’s folly,” most of the newspaper articles and correspondence found in the Seward papers during this time are staunchly in favor of the acquisition.

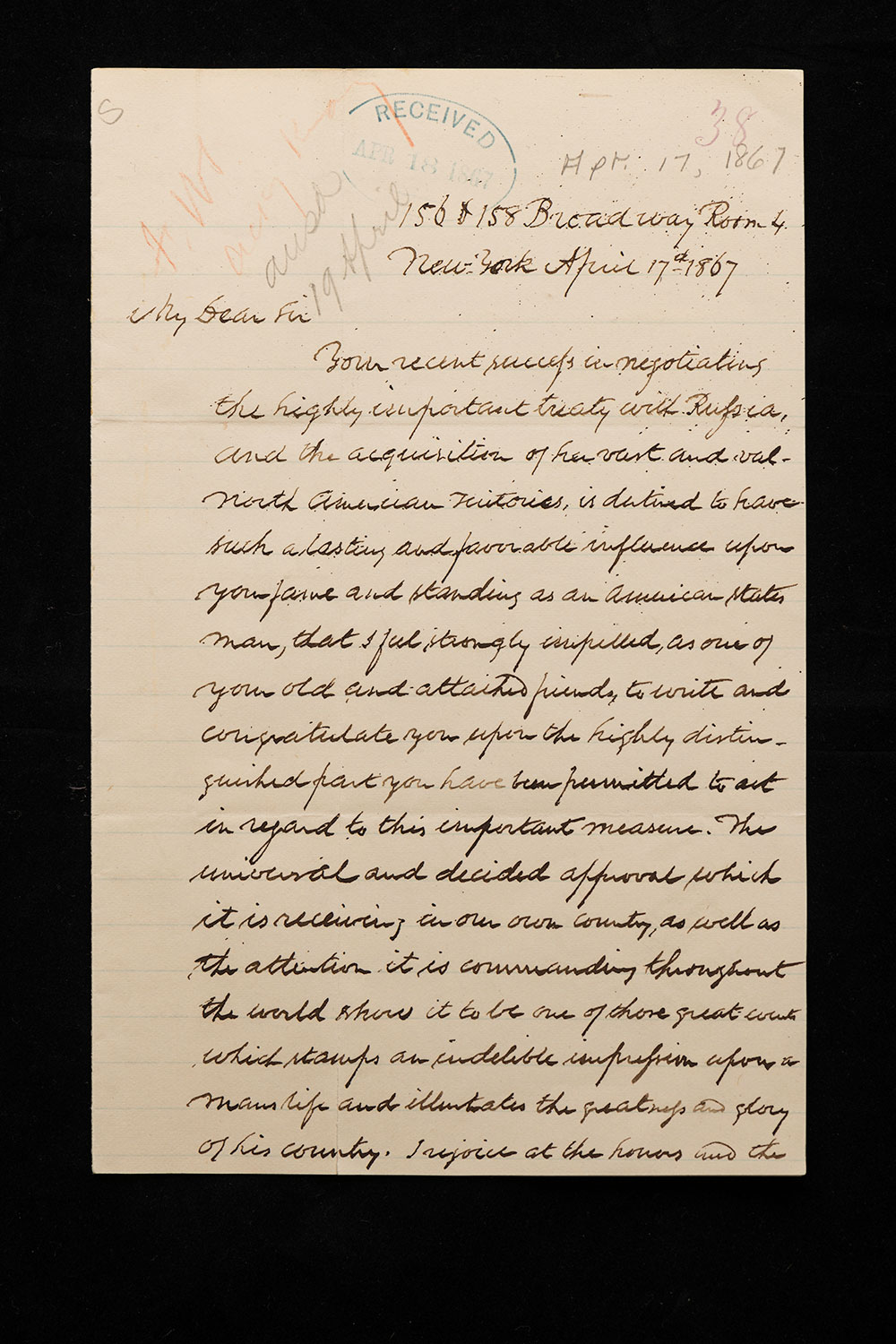

‘A lasting and favorable influence upon your fame’

One such letter in the Seward papers showing support for the Alaska Purchase is from Seward’s friend Henry Van Rensselaer Schermerhorn. Dated April 17, 1867, the letter praises the land acquisition: it “is destined to have such a lasting and favorable influence upon your fame and standing as an American statesman…[and] the attention it is commanding throughout the world show it to be one of those great works which stamps an indelible impression upon a man’s life and illustrates the greatness and glory of his country.”

Wish you were here

The painting on this postcard (“Signing the Alaska Treaty” by Emanuel Leutze) depicts the negotiations between Seward and de Stoeckl that led to the Alaska Purchase.

Seward holds a stack of maps and sits next to a large globe, suggesting the future of the United States as an expanding international power. Pictured from left to right are Robert Smith Chew, William Henry Seward, William Hunter, Jr., Waldemar de Bodisco, Eduard de Stoeckl, Charles Sumner, and Frederick William Seward.

The original 1867 painting currently hangs in the Seward House Museum in Auburn, New York.

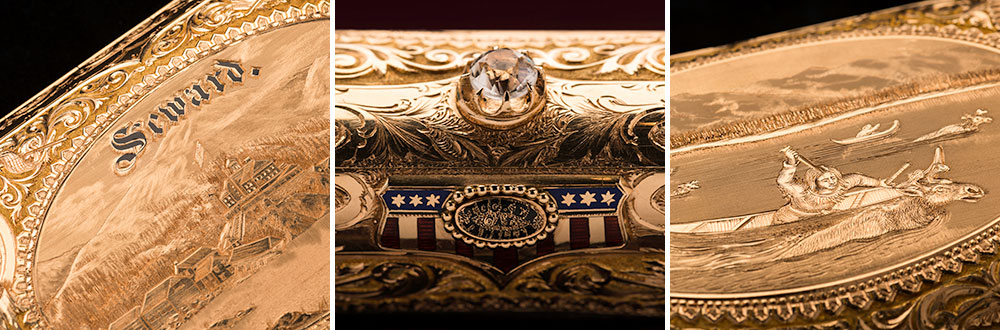

Commemorative cigar case

This 14-karat gold cigar case was gifted to Seward by the Pioneer Society of California in 1869 following his retirement from public office. It is decorated with scenes from Alaska, including a mountain range and coastal town, a walrus, a grizzly bear, and a Native American hunting in a canoe. The words “Alaska,” “California,” and “Seward” are engraved on top, commemorating Seward’s role in developing United States territories along the Pacific coast.