In December 1650, Baltazar de los Reyes was sold to an illiterate Spaniard in the city of Puebla de los Ángeles, southeast of modern-day Mexico City. News of the sale quickly spread in the close-knit community of the San Pedro hospital, where de los Reyes, a young black man, had worked alongside his mother. Both of them were slaves, owned by the hospital.

Three months earlier, a disagreement had erupted between the hospital’s powerful administrator and the young slave. As a result, the administrator had threatened to sell de los Reyes out of the city to a sugar plantation. That’s when young Baltazar decided to flee to Antequera—modern-day Oaxaca City—some 200 miles southwest of Puebla.

(University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

But the runaway slave made easy prey for bounty hunters, as Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva, an assistant professor of history at the University of Rochester, found by painstakingly searching through three colonial archives in Puebla.

“De los Reyes was now removed from the circle of family, friends and workplace acquaintances that had provided safety and community in Puebla. It effectively transformed him into a runaway slave, an esclavo huído, subject to corporal punishment and imprisonment by authorities with no ties to his community or the San Pedro hospital. Bounty hunters along the Puebla-Antequera road would be informed of his escape and remunerated for his capture,” writes Sierra Silva in his new book Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Ángeles, 1531–1706 (Cambridge University Press, 2018), which is due out in paperback at the end of this month.

Through close archival research, involving the state notarial archive of Puebla, the Puebla cathedral archive, and the Sagrario parish archive, Sierra Silva pieces together what happened next to the mother–son duo:

“Sure enough, by early December, bounty hunters had captured de los Reyes and sent him to the Antequera jail. He would soon be sold in absentia by two men 200 miles away,” Sierra Silva writes.

But here’s where the story takes an unexpected turn. Instead of heart-wrenching misery, the sale marks a triumph for this enslaved family, argues the Rochester historian. Piecing together fragments, Sierra Silva concludes that the young slave’s single mother, Sebastiana de Paramos, in fact orchestrated the entire sale in order to ensure her son’s safe return to the city, saving him from the backbreaking work on a sugar plantation.

“True, Baltazar de los Reyes would remain enslaved, but he would not, under any circumstance, become a fieldhand in some forlorn plantation. He would remain in Puebla, surrounded by friends, siblings, patrons, acquaintances, foes and former masters, as well,” Sierra Silva writes.

Sierra Silva, who arrived in Rochester in 2013, says he was initially drawn to the history of slavery in Mexico by a course he took in his last year in college at the University of Pennsylvania. “We had a reading on the ‘Black conquistadors,’ mostly West African men who participated in the Spanish military campaigns of the 1510s and 1520s against Native American states,” he remembers. “I had never heard of such men and was soon applying for graduate programs to learn more about their history and that of their descendants.”

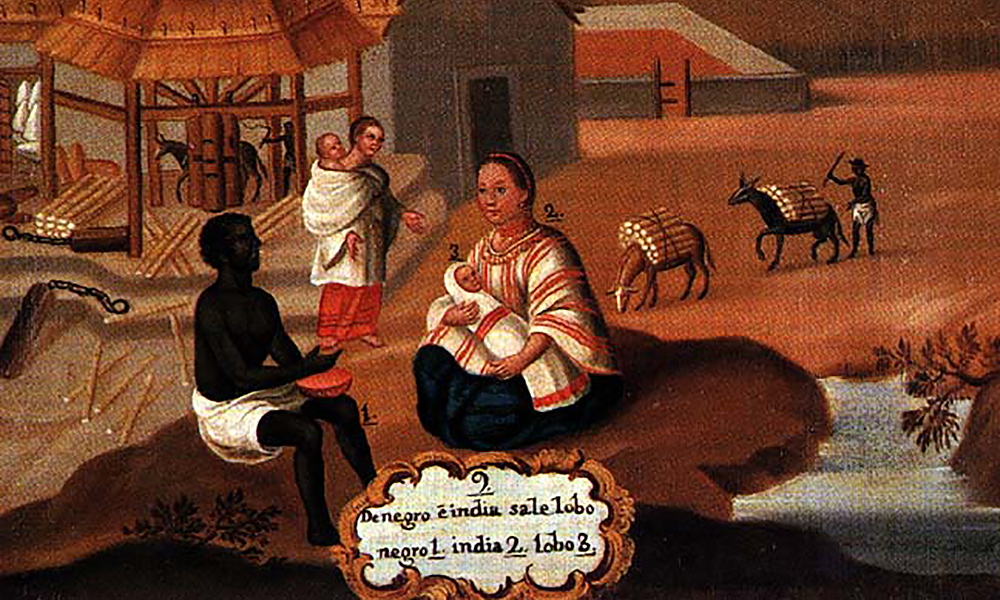

Today, Sierra Silva’s research focuses on the experiences of enslaved people, mostly Africans, South Asians, and their descendants, in the cities of colonial Mexico (New Spain) during the 16th and 17th centuries. Reaching beyond traditional master–slave narratives, he studies afro-indigenous interactions in the urban centers of central Mexico.

Sierra Silva discovered that at least 20,000 people were sold in Puebla’s slave market during the 17th century. What surprised him most, he says, was that the slave markets there surged once again in the 1680s, a development that previous studies had completely missed or disregarded.

“If anything, this new research suggests that a powerful, cultural demand for slave ownership continued well into the 18th century,” Sierra Silva says.

But unlike in more traditional plantation slavery, he argues that slaves in Spanish American cities had greater access to resources and allies that allowed them to lessen their masters’ control. Ultimately, by the end of the 17th century, enslaved families and their allies had successfully eroded slaveholder power in colonial Puebla, Sierra Silva finds.

Not resting on his laurels, he is now researching his next project. Last December, he was awarded a $50,400 fellowship by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to support his investigation of an infamous 1683 pirate raid on Veracruz that involved the violent capture and subsequent selling of between 1,000 to 1,500 Veracruzanos of African descent into slavery.

While history remembers the violent raid on Veracruz, little is known about its victims.